Banks Didn’t Listen to Buyout Boom Warnings. That’ll Cost Them.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Europe’s top finance watchdog is preparing to hit banks that lend aggressively to private equity with demands that they put more capital behind these activities. That’s what they get for not listening to advice.

The European Central Bank is increasingly concerned about leveraged loans, which are created by banks to finance buyouts and dividends. Andrea Enria, chairman of supervision at the ECB, warned banks in July that he would use all the tools he could to cut risks in this market.

Now, there are reports that lenders like Deutsche Bank and BNP Paribas could even face a limit on the amount of loans they can have on their balance sheets. In reality, though, capital charges are the best way to change behavior.

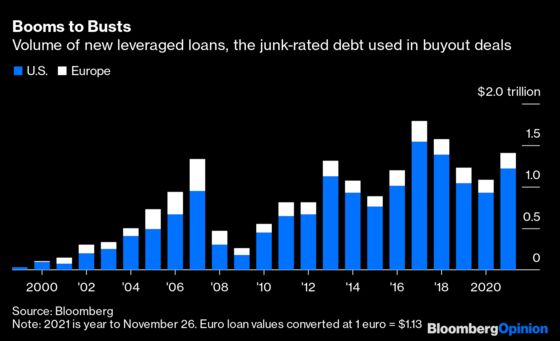

Buyouts are booming, accounting for about 20% of global mergers and acquisitions so far this year. What’s more, private-equity owners are borrowing record amounts to pay themselves dividends from companies they already own. The $1.4 trillion of leveraged loans in the U.S. and Europe in 2021 has already outstripped the total in all of 2007 — the peak before the 2008 financial crisis — according to Bloomberg data. By year end, issuance could get close to 2017’s record.

Private-equity owned companies are also borrowing more relative to their earnings. And it’s this fact that has really irritated ECB supervisors. They set out guidance in 2017 saying that loans that saddled companies with total debt greater than six times earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization should be very rare.

Banks flatly ignored this advice. The majority of deals being done by European banks are above that multiple, the ECB has found.

The supervisors could make the guidance stricter, but in truth it’s hard to police this kind of thing directly as U.S. regulators discovered a few years ago. In 2014, the Federal Reserve brought in rules on debt multiples for private-equity loans. Banks had to comply or explain to the regulator why they were breaching them. The calls were painful and big banks mostly pulled back from aggressive lending.

But the deals still got done – they just got outsourced. Smaller banks and non-banks that weren’t regulated by the Fed did the deals instead: institutions like Jefferies Financial Group, or the capital-markets divisions of private-equity firms like KKR & Co. And what’s more, those smaller firms got the funding they needed for these loans from the same big banks who had curbed such lending themselves, according to research from the New York Fed.

Of course, outsourcing could still happen whatever approach regulators take. This is an issue the ECB might still have to worry about.

However, capital charges are the simplest and quickest way to influence banks because the methods used to assess them and routes to impose them are already in place and easy to use.

The ECB can increase capital charges when it inspects banks’ internal risk models if it believes they use assumptions that are too optimistic, for example. Deutsche Bank had to put more capital behind leveraged loans and some other debts this year for this reason.

The central bank can also look at stress test results and add in capital requirements where it thinks a bank is just missing something in its risk management broadly. It assesses this each year for each bank in the Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process. This year’s SREP is already complete and will be published next month, but when the ECB starts the process again early next year, it could make leveraged loans a much bigger focus.

If there is still too much risky debt being created across the whole financial system, regulators also have a so-called countercyclical buffer that they can lift for all banks at the same time to give the industry extra protection against losses when the economy turns downward.

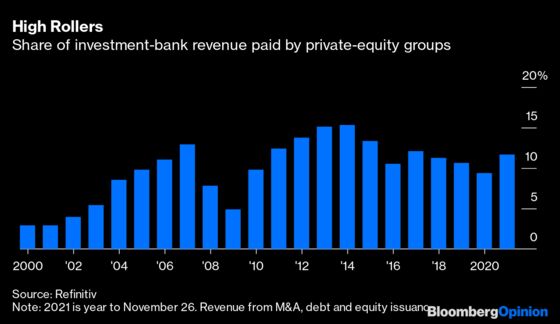

European banks will no doubt complain that extra capital charges would make them even less competitive with not only U.S. rivals, but also those in the U.K. and Switzerland, like Barclays and Credit Suisse. Private equity is big business for all these banks: Fees from such firms made up almost 12% of global investment banking revenue so far this year, according to Refinitiv, the highest share since 2017.

But U.S., British and Swiss regulators will all be looking at the global private equity boom with similar concerns. The threat of action by the ECB might just encourage others to act too. Banks everywhere should listen up.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Paul J. Davies is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering banking and finance. He previously worked for the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.