Why Some of Your Neighborhood Fixtures Are Disappearing

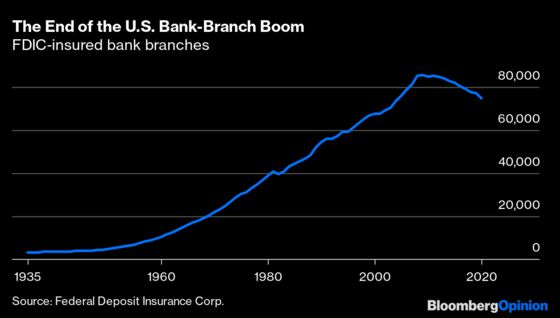

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- In the 2000s, the growing ubiquity of bank branches was one of America’s great retailing puzzles. Online banking was on the rise and the industry was consolidating, but branches kept popping up seemingly everywhere — if you define “everywhere” as the reasonably affluent parts of cities and suburbs.

That ended with the financial crisis. The number of bank branches in the U.S. has fallen 12% since 2009 even as the population has grown 8%.

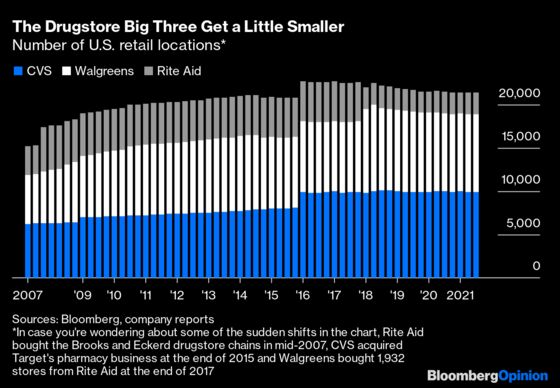

The growing ubiquity of chain drugstores during the same period was less of a puzzle. An aging U.S. population meant more prescriptions to fill, plus the major drugstore chains were buying smaller competitors and expanding into new areas of healthcare provision. But that boom seems to have ended now, too, with the number of locations for the three biggest chains down 6% since 2017.

“Big Three” is a little misleading, since grocer Kroger Co. has almost as many in-store pharmacies as Rite Aid has drugstores, and Walmart Inc. significantly more. But neither Kroger nor Walmart has been increasing its U.S. store numbers either, and with CVS Health Corp. just announcing plans to close 900 U.S. drugstores over the next three years and Walgreens Boots Alliance Inc. in a store-closing mood as well, it does look like we’ve passed peak chain drugstore in the U.S.

Given how much complaining there used to be about the surfeit of banks and drugstores, at least here in New York City, you’d think people would be celebrating in the streets. Instead, they’re complaining about the rapid-delivery grocery startups that have been gobbling up retail space lately. There’s also legitimate concern that places that never really saw the boom — rural areas and poorer parts of cities — are going to end up even more deprived of the products and services that banks and drugstores provide. While most of these can be provided digitally for banks, and most drugstore products can at least be ordered online, older and poorer consumers are less able to avail themselves of those options.

With banking there seems to be a pretty obvious policy response: allow some form of postal banking, which Bloomberg’s Editorial Board has endorsed from time to time. The banking industry has consistently fought against this, but as banks keep shuttering branches this opposition seems less and less tenable.

With drugstores, it’s not so clear that retrenchment by the chains will mean less availability. The number of independent pharmacies in the U.S. actually grew from 20,427 in 2010 to 23,061 in 2019, more than making up for the slight decline in the number of chain pharmacies (from 39,156 to 39,084) over that period.

One caveat: That’s according to a study conducted on behalf of a trade group that was battling legislative proposals pushed by independent pharmacists. The numbers are legit, but the choice of starting year is significant, given that from 2007 through 2009 hundreds of independent pharmacies had closed in the aftermath of the 2006 implementation of Medicare Part D, the prescription-drug benefit that made drugs more affordable for senior citizens but in the process made it harder for small pharmacies to break even on prescriptions. Still, the recovery since 2010 is impressive. Independent pharmacies in rural areas reportedly continue to struggle, but this likely has more to do with them being rural than being independent, and I’m afraid I have no simple fix to offer here for the struggles of rural America.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.