(Bloomberg Opinion) -- How’s this for a first world problem? Since the start of the coronavirus pandemic in Australia, my household has been finding it unexpectedly difficult to spend all of our wages.

Perhaps it shouldn’t be so surprising. Our two working-age adults are lucky enough to be in full-time jobs and haven’t really suffered any reduction in income due to the virus. On the other side of the ledger, many of our usual expenditures stopped or found themselves sharply reduced when lockdown started.

Working from home, I haven’t been buying lunch or taking the train to work. Visits to pubs, restaurants, cinemas or the theater (and the associated babysitting payments) stopped dead, and are only gradually returning as the outbreak recedes. Overseas holidays are out of the question. Once we’d bought a Nintendo Switch to help the kids make it through periods stuck at home, and replaced my old Samsung phone, we didn’t have many big-ticket items on our shopping list.

That’s precisely why Australia’s prescription for restarting the economy is a mistake.

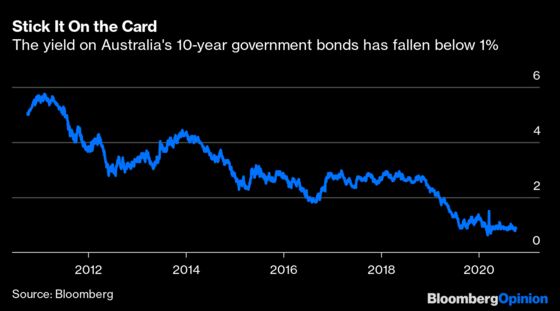

The centerpiece of the stimulus in Treasurer Josh Frydenberg’s budget announced Tuesday is the bringing forward of tax cuts originally slated to start in 2022, cutting income-tax thresholds at a cost of A$23.8 billion ($17 billion) over the two years through June 2022.

It seems rude to spurn a gift, but this promised increase in my family’s after-tax income is money we don’t need. The factor constraining my consumption isn’t a shortage of funds; it’s a lack of opportunities to spend them.

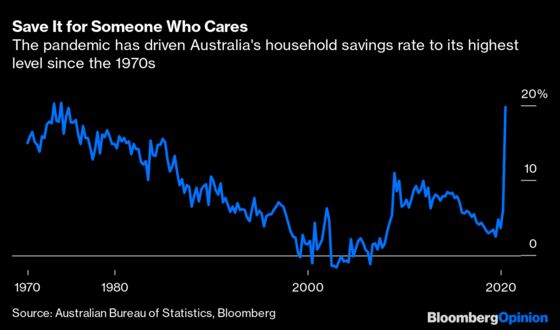

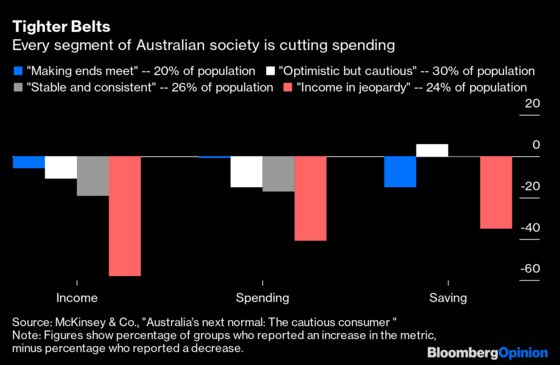

I’m not the only one in such a gilded bubble: About 26% of Australians, skewed toward the affluent, are in the same “stable and consistent” category in relation to consumer expenditure, according to an August study by McKinsey & Co. A further 30% on somewhat lower incomes are also reducing spending and increasing saving, the report found.

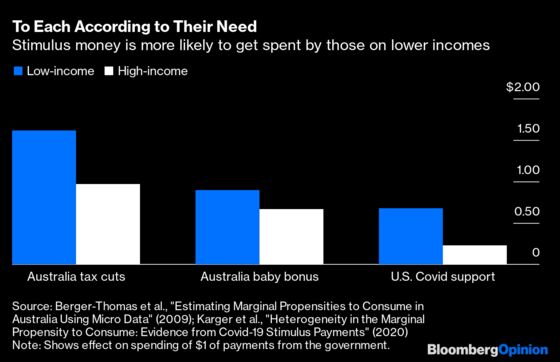

It’s long been known that the people most likely to use rather than save financial windfalls are the ones who are already struggling to make ends meet.

In a study led by then-Reserve Bank of Australia economist Laura Berger-Thomson into tax cuts and child bonuses made in the late 2000s, low-income households spent A$1.61 for every Australian dollar of tax cuts they received, compared to 97 cents for more affluent households. They also forked out 90 cents for every dollar of baby bonuses, compared to 67 cents for wealthier homes.

That pattern appears to be playing out in the current global downturn. Households living paycheck-to-paycheck disbursed 68 cents for each dollar received from the U.S.’s Covid-19 economic support program, compared to 23 cents among higher-income homes, according to a May study led by Ezra Karger of the Chicago Federal Reserve.

Australia’s initial Covid response was in many ways exemplary. Since June, the U.S. has barely seen a day when it didn’t add more cases than the 27,173 that this country has recorded since the start of the pandemic. With an outbreak in Melbourne during the southern winter finally being stamped out, it’s been nearly a month since more than 10 people died nationwide on any day.

Meanwhile, the government quickly dumped an irrational obsession with trying to chalk up a budget surplus in the face of a slowing economy. It established a JobKeeper program that’s given businesses incentives not to fire workers, helping to keep the decline in output to some of the lowest levels among major economies. It also added a temporary top-up to its JobSeeker unemployment-support program, which hasn’t seen a real-terms increase since the 1990s and which even employers’ lobby the Business Council of Australia argues is inadequate for the long-term unemployed to live on.

What Frydenberg needs to do is continue with what’s working rather than returning to a script that was already looking tired before the pandemic.

Tax cuts that only seriously kick in above median income levels won’t go to the sections of the population that are most likely to spur economic activity by spending them. Phasing out JobKeeper and JobSeeker on a fixed timetable over the coming months will withdraw support just when the economy needs it most. Plans to encourage investment by changing depreciation rules and the use of business tax offsets are welcome — but if they’re to help a consumer-driven economy recover they need to be combined with stronger incentives to retain and hire new workers, as well as buy new equipment.

To the extent that retail activity will pick up as the coronavirus recedes further, a temporary reduction in GST sales tax would have done far more to encourage the country to start shopping. Cutting income tax for the wealthier half of the population will just add to an already oversized savings pool, at a time when Australia needs every dollar spent now rather than deferred.

Australia has been one of the success stories of the pandemic. It would be a shame for it to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory now.

Median personal income in Australia was A$48,360 in 2017, the last year for which data are available.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.