(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Every so often, concerns crop up that inflation is much higher than official government numbers report. Sometimes people claim that rises in asset prices, or relative changes in living costs for some subgroups of Americans, represent hidden inflation. Others may cite an alternative inflation index that shows much higher price increases. But there's no reason to panic. Official government numbers do a good job of measuring the rate of inflation.

Inflation numbers are important because if inflation is actually running higher than the government numbers suggest, it means that either the Federal Reserve needs to raise interest rates or Congress needs to cut the deficit, or both. We're very likely to hear those arguments during the first few years of the Joe Biden administration — particularly as a reason to restrain spending. So here's some information to make better sense of the debate.

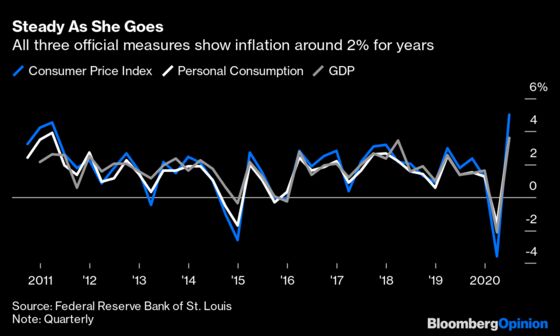

All the official measures show that inflation has been low — right around the government’s official 2% target — for years now.

But are these numbers accurate? Yes. To understand why, we have to first understand why economists try to measure inflation in the first place.

Suppose Congress passed a law that relabeled the value of a dollar so that it was only a 10th as much as before. Rent that was $2,000 a month would now be $20,000. A gallon of gas that was $3 would now be $30, someone who earned $50,000 would now earn $500,000, and so on. This relabeling wouldn’t really change anything about the real economy; the cost of rent and gas relative to people’s wages would be exactly the same as before.

That’s what inflation is supposed to measure: It's a relabeling of the numbers in the economy that doesn’t affect the real cost of things. Inflation is how we determine how much growth in nominal gross domestic product represents a genuine increase in the economy’s productive power. It tells us how much of people’s wage growth represents an actual increase in purchasing power, rather than just an empty relabeling. That’s why, when we adjust wages or GDP for inflation, we call the adjusted numbers the “real” numbers.

One thing inflation doesn’t include is financial asset prices, like stock prices. Apple Inc. stock doesn’t represent something intrinsically valuable, like housing or gasoline or human labor. It’s part of the financial economy, but not the real economy. Another way of putting this is that if wages stay flat and the price of food goes up, it means people are poorer — but if wages stay flat and Apple’s stock price goes up, people are no poorer than before. (For housing prices, it’s a little more complicated, since a house is both a financial investment and a real consumption good. Economists use a number called imputed rent to separate the part of housing that represents real and tangible value from the speculative part that’s more like Apple stock.)

Another thing inflation doesn’t measure is changes in the relative cost of living for different groups of people. If the price of food goes up and the price of yachts goes down, poor people lose out and rich people win. If rents go up in San Francisco but fall in St. Louis, San Franciscans are hurt and St. Louisans benefit. These are certainly real and important changes in the economy, but inflation is just one number, and it can’t measure all of these changes.

So when people say that asset price increases or changes in the relative living costs for different groups of Americans represent hidden inflation, they’re just wrong. Those are interesting and important changes, to be sure, but they’re not inflation.

Then there are the alternative inflation numbers that crop up from time to time. In the early 2010s, there was a website called Shadowstats that added a constant to inflation for no apparent reason. It was quickly debunked. Now some people are citing a number called the Chapwood index, which claims that inflation has actually been running at an annual rate of 10% to 12% rather than the official 2%.

First of all, 12% obviously can’t be the real inflation number. If true, it would mean that the productive power of the U.S. economy would be falling by half every eight years or so. Here’s a picture of what GDP growth would look like if inflation were actually running at 12%:

If you think the American economy has been shrinking rapidly and continuously since 1985, you need to think again.

The Chapwood index’s methodology is extremely dodgy and opaque. It’s based on a survey of the creators’ friends and relatives. It includes dubious items such as “federal,” “property” and “lunch,” as well as things almost no one buys, such as “luxury box rental” and “horseback riding lessons.” It weights these items by their price rather than by the total amount people spend on them, meaning things that go up in price faster will be a hugely outsized part of the index. And so on.

If you want an alternative inflation measure, a good one exists. It’s called the Billion Prices Project, run by some professors from MIT. The BPP gets data from online retailers in order to measure the prices of as many goods as they can, then combines them in a manner that represents how much people actually spend on each. For some countries, like Argentina, they find that official government inflation numbers are indeed quite understated. But for the U.S., the numbers match up quite nicely.

So as the debate over stimulus spending rages, you can be confident that government inflation numbers are as good as we can make them. They measure what they’re supposed to measure, and there are no secret numbers showing that inflation is actually much higher. So don’t let anyone get you worried about inflation — it really is low right now. And if it rises in the future, official numbers will let us know.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.