(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The biggest question facing U.S. stock investors isn’t about the pandemic or economic growth or even inflation. It’s about whether the stock market can maintain its historically high valuation, a perch it has commanded for most of the past three decades. Investors who want to know what to expect from the market in the coming years must address that question, and there is a lot riding on the answer.

For about 120 years from the 1870s to the 1980s, the U.S. stock market reliably reverted to its long-term average valuation, and just as important, it spent roughly equal time above and below that average. Investors could therefore expect an expensive market to become cheaper and a cheap market to become more expensive, a useful assumption when estimating future stock returns. Change in valuation is one of three key components of returns, along with dividends and earnings growth. The ability to anticipate where valuations are headed makes forecasting easier and more reliable.

Since 1990, however, the market has rarely dipped below its long-term average valuation, the notable exception being the period around the 2008 financial crisis. Neither the dot-com bust in the early 2000s nor the Covid-induced sell-off last spring managed to subdue it.

The difference between the two periods is striking. From 1871 to 1989, the market traded below its long-term average valuation 47% of the time, as measured by price-to-earnings ratio using 12-month trailing earnings and counted monthly. Since 1990, that percentage has dropped to 10%. The results are similar using the cyclically adjusted P/E, or CAPE, ratio, which swaps prior-year earnings with an average of inflation-adjusted earnings during the previous 10 years. Based on that measure, the market was less expensive than its long-term average CAPE ratio 50% of the time from 1881 to 1989 but just 5% of the time during the last three decades.

The market’s lofty valuation in recent decades has baffled forecasters, with far-reaching consequences because return forecasts are a chief component of most portfolios and financial plans. Money managers use them to allocate among investments. Planners use them to gauge how much workers must save for retirement and the pace at which they can spend those savings when they get there. A good forecast can also help investors set realistic expectations, which makes it easier to stick with a portfolio or financial plan.

Unfortunately, past performance is no indication of future results, as investors are constantly warned, which is why big reputable money managers spend considerable time and energy honing their estimates of future returns. In essence, their forecasting models disaggregate the components of stock returns and come up with an estimate for each variable. There are many variations — some account for buybacks, others break out earnings growth into smaller components such as sales or profit margins. But every model must grapple with where valuations will land at the end of the forecasting period, particularly now that valuations have a lot of room to contract and potentially dwarf all other factors.

Thus the conundrum: Is it safe to assume the market will revert to its long-term average valuation? Asked another way, are the last three decades an anomaly or a new normal?

The answer leads to much different estimates of future stock returns. Let’s assume, for example, the dividend yield will be 1.3% a year over the next 10 years, which is the current yield for the S&P 500 Index, and that earnings will grow 5.6% a year, which matches the S&P 500’s earnings growth since 1990. That amounts to an expected return of 6.9% a year over the next decade before accounting for any change in valuation.

The market’s valuation will almost certainly be different in 10 years, though. In fact, multiyear swings in the P/E ratio have been as wild as ever in recent decades, even though the average P/E ratio has remained elevated. And given the market’s high valuation today — by any measure one of the highest on record —it’s reasonable to assume the valuation will be lower in 10 years.

But how much lower? If the last three decades are an anomaly and the market’s valuation can be expected to drift toward its long-term average P/E ratio of 16 or 17, depending on the measure of earnings, then the valuation would have to contract by about 8% a year over the next decade, producing a negative expected return of 1.1% a year. On the other hand, if the last three decades are a new normal and the valuation can be expected to hang around its average P/E ratio of 25 since 1990, then the valuation would need to contract by just 3% a year, which pegs the expected return at closer to 3.9% a year. (The result is about the same using 12-month trailing or cyclically adjusted earnings.)

That’s a big difference, and it explains much of the variation in expected returns for U.S. stocks. JPMorgan Asset Management, for instance, appears to embrace a new normal. It estimates a valuation drag of about 3% a year over the next 10 to 15 years, producing an expected return of roughly 4%. Boston-based money manager GMO, by contrast, appears to doubt that things have changed. It estimates a negative inflation-adjusted return of 8% a year from U.S. large-cap stocks over the next seven years, a result that is inconceivable without a drastic contraction in valuation.

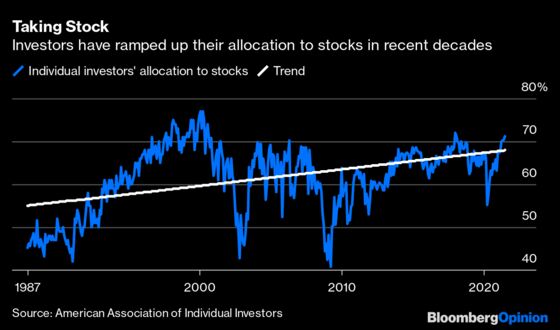

As the years go by and the market maintains its elevated valuations, it becomes easier to suspect that something has indeed changed for good. And of course, many things have. Financial markets are accessible to more people than ever before, and it’s much easier and cheaper to buy stocks today than it was three decades ago. Investors are allocating more of their savings to stocks, much of it in index funds that track the broad market, and they appear to be getting better at hanging on to them. Retirement plans also steer billions of dollars to the market every year. It’s not hard to imagine that an increased demand for stocks and a decline in the number of panicky investors has lifted the market’s average valuation.

That doesn’t mean the market won’t crater occasionally, as it did during the financial crisis. But there’s a growing chance that the past 30 years haven’t been an anomaly and that forecasting models need to lift their valuation targets.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nir Kaissar is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the markets. He is the founder of Unison Advisors, an asset management firm. He has worked as a lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell and a consultant at Ernst & Young.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.