(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The law of conservation of energy is ingrained in every high school science student: Energy can’t be created or destroyed, only transformed or transferred.

The global natural gas market represents the political version of that primary tenet of thermodynamics.

Europe’s demand for liquefied natural gas (LNG) to replace Russian imports has now been transferred to the U.S. Until now, shipping American LNG into Europe has been a policy that's won accolades for President Joe Biden. Politically, it helped contain Vladimir Putin, and economically, it boosted the U.S. energy industry. It has also helped to rebalance the trade deficit. Now comes the greater test. As the American gas market begins to connect with the European one, the price problems in Europe are crossing the Atlantic.

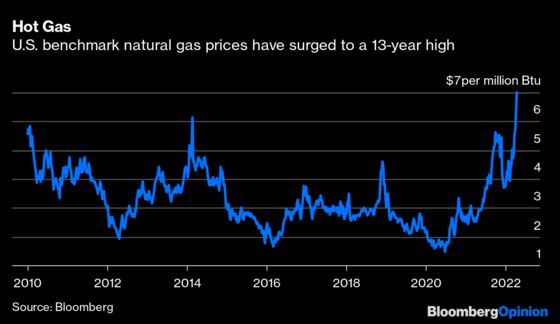

On Monday, the price of benchmark U.S. gas surged to a 13-year high, exceeding $8 per million British thermal unit, more than double the 2010-2020 average Americans paid of about $3.3 per million Btu. Though still a fraction of the more than $30 per million Btu that European consumers are paying, American prices are already feeling the tug of demand in the continent.

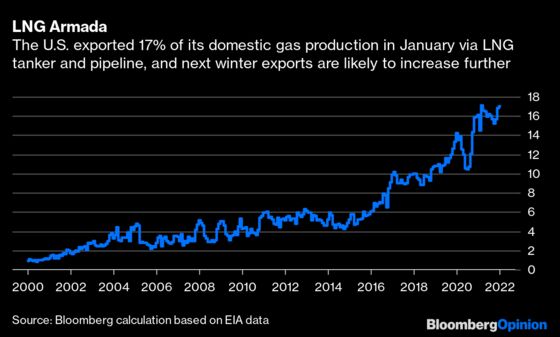

Natural gas markets have historically tended to be regional. Until recently, the U.S. market was almost an island, connected only to Mexico and Canada via limited pipelines. But in the past six years, the U.S. gas industry has slowly linked up to the rest of world as liquefaction facilities opened up in Texas, Louisiana, Maryland and Georgia.

Thanks to all those LNG terminals, the U.S. exported 17% of its domestic gas production in January, the last monthly data available. By next winter, the U.S. Energy Information Administration, a government body, forecast that one-in-five molecules of gas produced in America will be sold overseas. Two decades ago, the U.S. barely exported any gas at all.

U.S. gas production has not kept pace with the surge in exports and stronger-than-expected domestic demand. As a result, American gas storage facilities have emerged from winter far emptier than expected. As of last week, inventories stood at roughly 17% below the five-year average for this time of the year.

To be sure, cold weather has kept demand elevated, and freezing temperatures in the key production region of west Texas have hampered output. But there’s a structural element too: U.S. shale companies aren’t responding to high prices as they did in the past, as they prioritize profits-over-volume. The number of rigs drilling for gas in America stood at about 150 last week, far below the nearly 1,000 of 13 years ago, the last time that gas prices were above $7 per million Btu.

Part of the reluctance to drill more is due to fears about a price collapse if the weather cuts gas demand and the economy slows down in late 2022 or early 2023. Another problem is sky-high inflation for steel, a key input into drilling for gas, and other supply bottlenecks. Nor do industry executives mind making life harder for Biden ahead of mid-term elections in November. Although the Democratic president has now embraced the oil and gas sector, he had campaigned on an ambitious environmental agenda, famously promising that he was "going to end fossil fuels." Wall Street has also become reluctant to finance the industry over climate-change concerns.

There’s another fear: that Europe won’t consume as much American gas as it plans today if the war in Ukraine ends soon. In private, many U.S. shale executives believe that Germany will ultimately stick with Russia.

Without more drilling, the U.S. will struggle to rebuild inventories this summer, particularly if hot weather increases demand for air conditioning. In turn, power plants will consume more gas to produce electricity.

In the options market, gas traders are already betting for higher prices later this year, and into next winter. For example, the amount of outstanding contracts for call options that will pay if prices reach $10 and $15 per million Btu by March 2023 has surged recently. Although the bets aren’t a forecast, it’s an indication of the balance of risks.

If those risks materialize, the price surge may trigger a political storm next winter. In February, a group of senators, including Elizabeth Warren, wrote a letter to the Biden administration urging a “swift action to limit U.S. natural gas exports,” warning that without it, families will see “even larger increases in their heating bills.” Since then, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has redrawn the world’s energy map and Biden has promised to do the opposite of what the senators requested: He traveled to Brussels and pledged more American LNG supplies to help Europe unplug itself from Russian gas.

Biden should not waver on its support for more U.S. LNG exports, even if that means higher prices — and another inflation headache. But he does need help from the shale industry, which has the advantage of geology: the prolific Marcellus and Permian gas basins. For much of the industry’s complaints about Biden’s often incoherent energy policy, the truth is that the White House has already secured a new market for U.S. gas exports in Europe. All that’s needed is the extra gas. Both the Biden administration and the U.S. shale industry need to sit down and make it happen.

More From Bloomberg Opinion:

- U.S. Energy Independence Will Provide Small Comfort: Justin Fox

- Germany Must Cut Off Russian Gas Sooner, Not Later: Chris Bryant

- A Better Way to Sanction Russia's Oil: Meghan L. O'Sullivan

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Javier Blas is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy and commodities. He previously was commodities editor at the Financial Times and is the coauthor of "The World for Sale: Money, Power, and the Traders Who Barter the Earth’s Resources."

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.