(Bloomberg Opinion) -- At the American Economic Association’s big annual conference last week, one of the most-attended sessions was a panel entitled “Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism.” The panelists included economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton — the co-authors of a recent book with the same title as the panel — as well as sociologist Robert Putnam and economists Raghuram Rajan and Kenneth Rogoff. Together, they painted a bleak picture of a fraying society. But this picture ignores the ways in which American culture has begun healing itself in recent years.

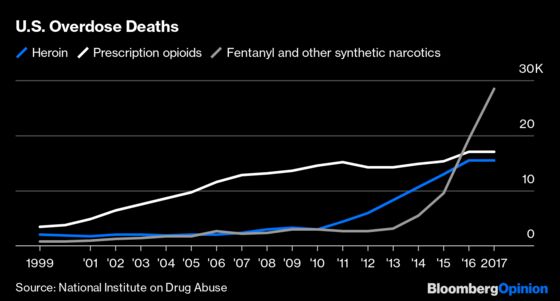

The main evidence Case and Deaton cite in their book is the rise in mortality from suicide, alcoholism and drug overdoses. All of these social ills have increased in the U.S. in recent decades among all adult age cohorts. The wave of deaths from opioids has been especially horrifying:

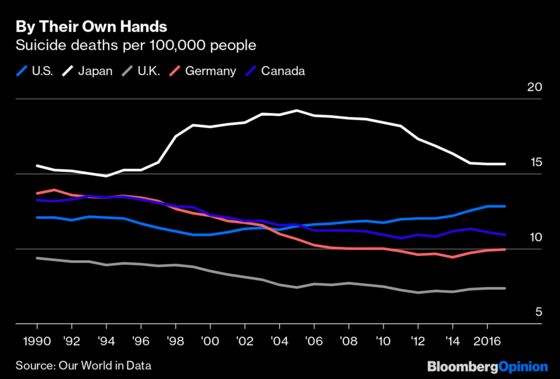

Meanwhile, even as suicide rates have fallen in many countries, they have risen in the U.S.:

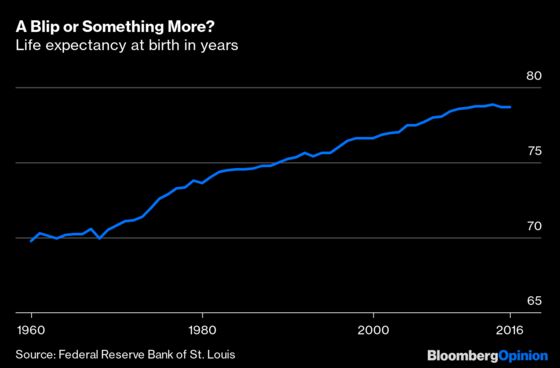

Deaths from alcohol show a similar pattern. In combination, these are among the factors accounting for a plateauing of U.S. life expectancy:

Putnam, who studies social isolation, added some more indicators of social breakdown. Marriage rates have stabilized for educated people, but have fallen steadily among those without college degrees. Church attendance and volunteer work, two traditional indicators of social participation, are also way down. Overall, the data presented by the panelists paint an ugly picture of an American people huddled in their bedrooms, playing video games, doing drugs and dying prematurely and alone.

The panelists speculated on the causes of this epidemic of deaths of despair. The economists, perhaps unsurprisingly, blamed economic factors — the decline of manufacturing, the dysfunctional U.S. health-care system, the emptying of small cities as industry has clustered into a few big metropolises. Putnam focused on cultural factors, blaming a rise in individualism since the 1960s.

If the economists are right, the solutions lie with policy. Case emphasized universal health care — one area in which the U.S. clearly lags other developed nations. Policies to help struggling places, increase the bargaining power and dignity of regular workers, and provide more income support could also play a role.

Those are all good ideas, even if deaths of despair weren’t rising. But the narrative that U.S. society is coming apart needs some perspective. Some trends are bad, but others are positive.

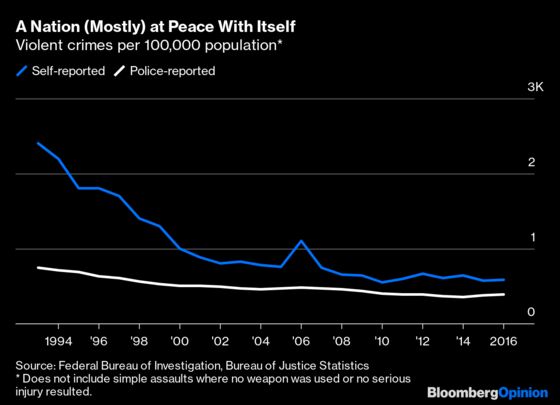

For example, the U.S. is much less violent than it used to be. Although the country still has higher violent crime rates than other rich nations, things have gotten much better in the last 30 years:

A modest increase in homicides in 2015 and 2016 turned out to be a temporary blip. Domestic violence has fallen significantly, suggesting that the decline isn’t simply due to changes in illicit drug markets or gang culture; Americans really are attacking each other less.

Meanwhile, young Americans are engaging in less risky sexual behavior. In 1991, 54% of American teens had had sexual intercourse; by 2017, it was 40%. This is one reason for the big drop in teen pregnancy rates, which have fallen by about a third since 1990.

Sexuality is only one way in which U.S. teens have become healthier. They are doing fewer illegal drugs and drinking less alcohol, even as their elders do more of these things. Prescription opioid use among teenagers has also fallen substantially during the past decade.

In addition, many of the negative trends highlighted by Case, Deaton and Putnam might be less ominous than they seem. The gap in life expectancy between the U.S. and other rich countries isn't much greater than it was 30 years ago, and other rich countries may also now be hitting a plateau. The rise in suicide is worrying, but the rate isn’t much higher than it was in 1990 (and for teens it’s lower). Even the horrifying opioid epidemic may now be starting to recede; drug overdoses fell in 2018.

Thus, a broader look at U.S. trends show a society that is coming apart in some ways but has knit itself back together in others. An observer time-traveling from 1990 might be astonished at how the social panics of their day — spiraling violence, self-destructive behavior by young people — seem to have receded.

As for loneliness and social disconnect, these may not resolve themselves in the way that sociologists such as Putnam expect. Volunteer work and church attendance may be replaced by online activities as people substitute physical interaction with digital.

None of this should be taken to imply that Americans don’t have deep economic problems that need addressing. Policies such as national health insurance, regional revitalization, a better social safety net and a corporate system that rewards workers more are good ideas regardless of the nation's other social ills. Political polarization may yet tear the country’s institutions apart. But the vision of the U.S. as a disintegrating society isn't as dire as many believe.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.