America’s Immigration Crisis Goes Beyond the Border

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Call it progress: When President Donald Trump unveiled a plan in May to reform the U.S. immigration system, he said that the number of immigrants granted green cards each year would remain unchanged. That’s a U-turn from his 2017 endorsement of a bill that could’ve halved annual admissions, currently running at about 1.1 million. The new plan promotes a merit-based system that privileges skills and education over extended family ties. But it is short on detail, lacks political support even from Republicans, and is at odds with the administration’s record of imposing new restrictions on skilled immigrants.

This ambivalence and disarray, although more pronounced in Trump’s administration, exemplifies the approach America has taken to the issue for decades. Even as the country grows more dependent on new arrivals, its policies toward immigrants — skilled and unskilled, legal and illegal, refugees and asylum seekers — remain confused and ill-considered. Change has rarely been so urgent.

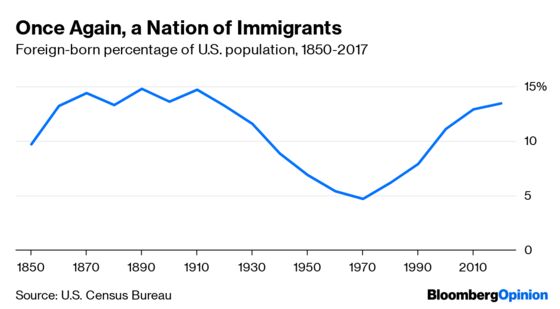

It’s true that the U.S. has undergone a significant demographic shift in recent decades. In 1970, only 4.7 % of its inhabitants were foreign-born. By 2017, the number had risen to 13.6%, close to its historical peak of 14.8% in 1890.

But the fact is, the country needs more immigrants of every kind. It needs innovators, entrepreneurs, scientists, engineers and other skilled workers for its economy to thrive. It needs crop-pickers and health-care workers to do jobs native-born Americans generally don’t want. It also needs to resolve the status of more than 10 million undocumented residents. And as the world’s most powerful democracy, whose strength and legitimacy depend on living up to its values, it has compelling reasons to fix its broken systems for aiding asylum seekers and refugees.

The starting point for thinking about these challenges is to recognize how important immigrants are to the U.S. economy. According to the New American Economy Research Fund, immigrants and their children established nearly half of today’s Fortune 500 companies. In 2017, they made up about 17% of high-skilled working males. In Silicon Valley, more than half the workers in STEM fields — and an even higher proportion of software engineers — were born overseas.

In all likelihood, the importance of immigrants will grow in the digital age. There’s good evidence that high-skilled immigration promotes innovation. Immigrants are almost twice as likely as the native-born to start new businesses, and in 2014, they made up about 20% of all entrepreneurs. Figures compiled by Bloomberg show that “states with the greatest concentration of immigrants create the most jobs and biggest increase in personal income.”

Demographics, meanwhile, are making America’s needs more acute. A country with fewer babies and more old people has greater need of immigrants. Last year, the U.S. population grew at its slowest pace since 1937. Nearly one-fifth of states have lost residents during the last two years. Alaska, Maine and Vermont — along with numerous cities and towns across the country — are even offering bounties to newcomers.

Other things equal, this means slower economic growth, and an aging workforce pushes the same way. Fewer workers supporting more retirees will put Social Security and other public pension plans under further strain.

In short, the U.S. can’t afford an immigration system that saw its last major overhaul half a century ago.

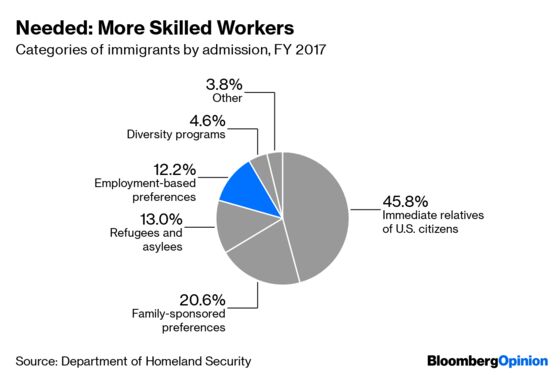

By any measure, America’s formal immigration processes are confusing and often arbitrary. Every year, for instance, 50,000 visas are allotted by lottery (in 2018, nearly 15 million people applied). Currently, the U.S. allocates 140,000 visas each year to employment-based immigrants — only about 12% of the total admitted in 2017. Two-thirds were granted on family ties.

On balance, it makes sense to prioritize an increase in skill-based immigration — as Trump proposes — where the economic benefits are greatest and most obvious to current citizens. But how might this be done?

Consider the system as it stands. Like most U.S. immigration procedures, the road from bright student to happy permanent resident is tortuous. Let’s say you get a student visa. Upon graduation, you’re entitled to a period of paid practical training. If your goal is to stay in the U.S., you find a company to sponsor you for an H-1B visa as a specialized worker. But Uncle Sam allocates only 85,000 of these annually, so you have to pray that yours is picked in a lottery. This year, 201,011 petitions were submitted. If you’re one of the lucky ones, your petition and visa must then be approved. Retaining your visa depends on retaining your job. Hold onto both and you can apply for a green card. But guess what? There’s a per-country cap of 7% of allotted visas each year. If you’re from a high-demand country like China or India, you’re in for a long wait — as of April 2018, it amounted to 17 years for Indians with bachelor’s degrees and, perversely, 151 years for those with advanced degrees.

No wonder Canada has made the U.S. process a selling point for its own visa program, or that Australia came out ahead of the U.S. in a recent survey of national attractiveness to talented migrants.

The Trump administration seems determined to make things worse. Student visa issuances fell from about 678,000 in 2015 to 390,000 in 2018. Even though the law regarding H-1B visas hasn’t changed, the denial rate surged from 5% in 2012 to 32% in 2019, including for seasoned petitioners such as Amazon.com Inc. Proposed regulations will put new limits on the time students can stay in the U.S., strip work permits from spouses of H-1B holders, and narrow eligibility for work visas.

In fairness, the still-undefined points system Trump has aired could be an improvement. Similar systems in Australia, Canada and New Zealand balance the need for high-skilled workers with longer-term objectives, and create a more transparent and objective process. A comparable approach could be applied to semi-skilled workers in agriculture, health care or other fields in demand. Among other benefits, such an arrangement could avoid the per-country caps that have kept the U.S. from turning China and India’s brain drain into America’s gain.

But the transition will face a big obstacle: What to do about the nearly 4 million immigrant petitions, most of them family-based, already on file? To keep faith with those applicants, give them the option of staying in the existing lengthy queue or submitting an application under a new system that awards some points for family ties, with the prospect of a speedier entry. The U.S. could also afford to ease the overall backlog — so long that applicants are dying out of the system — by increasing the number of green cards per year, say to 1.4 million or so.

******

Unfortunately, Trump’s approaches to the other huge challenges facing the immigration system are less coherent — or even counterproductive.

Start with the undocumented. Trump’s fixation on an expensive and ineffective border wall has diverted resources from other priorities. His slandering of undocumented immigrants has sown division and made it harder to resolve their fate politically. And his administration’s cruel and incompetent enforcement strategies have gravely harmed families and children while failing to deter newcomers and damaging America’s reputation and relations with its neighbors.

If Trump wants to reduce illegal immigration, he should instead be pushing long-delayed initiatives such as an effective entry/exit system that can curb the visa over-stayers who have outnumbered illegal border crossers in recent years. He could encourage wider use of the E-Verify system to block illegal workers, and step up prosecutions of those companies that employ them; last year, only 11 employers faced charges. Instead of cutting aid to Central America, he should bolster it, while also using U.S. leverage to persuade its leaders to invest more in their people instead of exporting them to earn remittances.

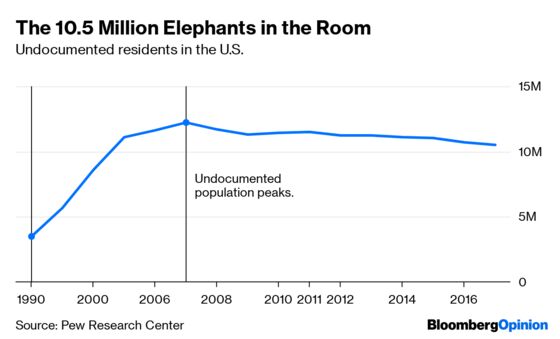

As for the millions of undocumented already living in America, Trump proposes mass deportations — an idea that would take years, cost several hundred billion dollars, and likely cause U.S. GDP to contract by more than $1 trillion. (The U.S. deported about 295,000 people in 2017, down from 435,000 in 2013 under Obama.) For all Trump’s hyperventilating about an “invasion” of the U.S., the undocumented population fell from 12.2 million in 2007 to 10.5 million in 2017.

The quickest, smartest and most compassionate way to shrink the undocumented population further would be to legalize the million-plus people in the U.S. already under some form of temporary protection. More than 400,000 immigrants, for instance, have been given Temporary Protected Status from deportation back to countries suffering from natural disasters, war or civil unrest. Another 700,000 — the so-called Dreamers — have had temporary protection under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program.

Both groups deserve compassion. Dreamers were brought to the U.S. by their parents, raised and educated there, and know no other home. Many under TPS have now been in the country for decades. In 2017, the two groups contributed more than $5.5 billion in taxes, and represented $25 billion in spending power. The lives they’ve built include businesses, jobs and homes, as well as nearly 300,000 children who are U.S. citizens by birth. Sending them back to their countries of origin, especially the Dreamers, would not only betray America’s values but squander taxpayers’ investments in their educations and upbringing. Far better to legislate a path to legal status and terminate or revamp TPS to avert the creation of similar limbos in the future.

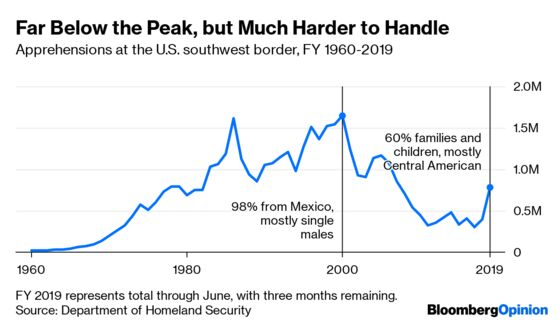

Asylum is another area where Trump’s approach is making a bad situation worse. Nothing illustrates the absurdity of his wall preoccupation more than the tens of thousands of Central American asylum-seekers wanting to turn themselves in to the Border Patrol rather than evade it. The system is undeniably broken: Families seeking to escape poverty, not persecution, exploit its inconsistencies and weaknesses with the help of criminal gangs that profit from their misery.

But the answer to these problems isn’t more troops at the border or overblown states of emergency. It’s more judges and clerks for the immigration courts, more asylum officers who can process cases quickly, and more humane shelters that don’t prompt fervid comparisons with concentration camps. The best way to deter future unmerited claims is to resolve them quickly so the word gets out. And yes, there’s nothing wrong with deporting families whose asylum claims have been rejected: If you want the public to support asylum, it must believe that the system is credible as well as compassionate.

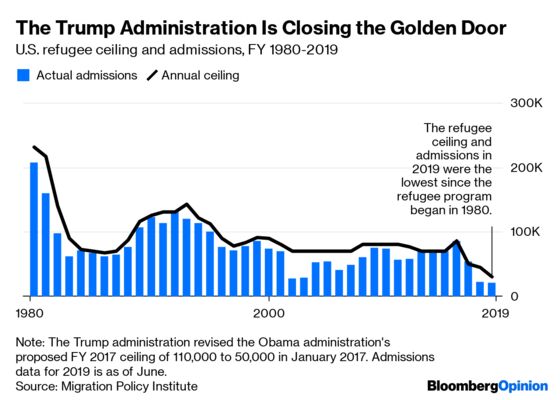

A final concern is refugees. Trump has done his best to transform America’s policies from a beacon of global hope into a darkening blot on its reputation. One of his first acts in office was to suspend refugee admissions, citing dubious security threats. (Unlike asylum applicants who simply show up at U.S. borders, refugees must undergo extensive screening before they’re approved for resettlement.) Since then, he has repeatedly lowered the ceiling for refugees and slow-rolled even those reduced admissions: Last year, when the ceiling was set at 45,000, the U.S. admitted just 22,491 refugees — the lowest number since passage of the 1980 Refugee Act. This year, with the number of displaced people worldwide at a record high, the ceiling is even lower: 30,000. In 1980, the U.S. admitted 207,116.

America’s moral standing aside, such stinginess does the country no favors. A 2017 government study, which the Trump administration tried to suppress, estimated that from 2005 to 2014, refugees actually generated $63 billion more in government revenue than they cost. They’ve revitalized ebbing communities in Maine, Missouri, New York and more. Their rate of entrepreneurship is higher even than ordinary immigrants. And they’re more likely to become U.S. citizens — a proven boost to everything from income to home ownership. Dollar for dollar, person for person, the 3 million refugees that the U.S. has resettled since 1980 have been an invaluable investment.

******

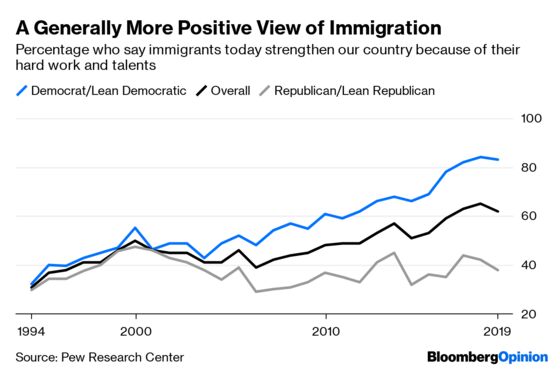

Fortunately, overall attitudes about immigration have undergone a positive sea change in the U.S. since the 1990s, the decade that saw the second-biggest jump in the proportion of the foreign-born population (after the 1850s). Polls show much greater recognition of the benefits that immigrants bring, and a diminished sense of the threats they pose.

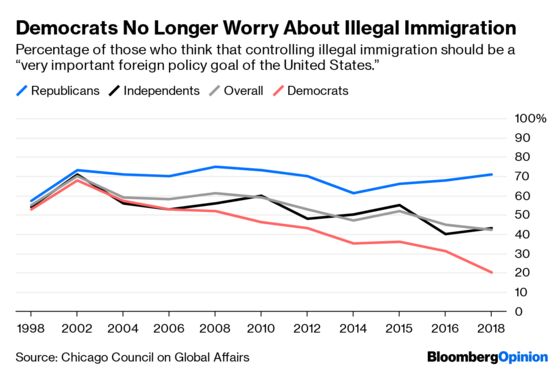

Yet underlying this shift is a polarizing trend that impedes serious reform: Even as Democrats and independents have become much more supportive of immigrants and tolerant of illegal immigration, Republican attitudes have slightly hardened. The partisan gap on immigration is by some measures at a historic high. At its crudest level, this dynamic has translated into a Republican Party that resists even modest fixes to immigration laws, and a Democratic Party that refuses to talk seriously about enforcing them.

Republican intransigence, for instance, is largely to blame for the failure of the last big attempt at comprehensive immigration reform. In 2013, House Speaker John Boehner refused even to hold a vote on the Senate’s so-called Gang of Eight bill, a bipartisan and badly needed measure that included a more merit-based system and a path to citizenship.

Today’s Democrats, meanwhile, don’t exactly talk the walk on enforcement. When the New York Times recently asked 21 of the 2020 Democratic candidates for president if they thought “illegal immigration is a major problem in the United States,” only four mustered a yes or no. The rest served up the kind of soggy waffles you’d expect at a campaign diner stop.

The fact is, both parties are going to have to commit themselves to making significant changes in the American immigration system in the coming decades and reconciling their differences. Fat chance of that, you might think — especially given the polarized discord on the issue since the failure of the Gang of Eight bill and the coming of Trump.

Yet the past offers a hopeful precedent. In 1977, Congress stiff-armed President Jimmy Carter’s proposals on immigration reform, which were sparked by rising illegal Mexican immigration. But that defeat helped birth initiatives and bills that led to the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, the last big reform Congress passed.

Resolving today’s even more complex challenges will require the kind of bipartisanship and pragmatism that have proved elusive in recent years. Let’s hope that the presence of more than 10 million undocumented residents, the crisis at the border, and the growing global competition for immigrant talent prove to be catalysts that recall Americans to their senses. The demographic and economic future of the United States depends on it.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Timothy Lavin at tlavin1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

James Gibney writes editorials on international affairs for Bloomberg Opinion. Previously an editor at the Atlantic, the New York Times, Smithsonian, Foreign Policy and the New Republic, he was also in the U.S. Foreign Service from 1989 to 1997 in India, Japan and Washington.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.