(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The U.S. labor movement has been moribund for decades, but a high-profile unionization drive at Amazon.com Inc. may be just what it needs to revive its fortunes. That's because Amazon workers embody a new working class that may start to develop the kind of solidarity that existed among factory workers last century.

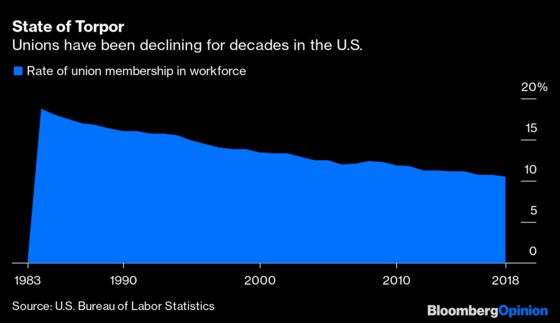

The last 40 years haven't been good to unions in America. Since 1983, union membership has fallen by almost half, to the point barely one worker in 10 is organized:

There have been some rumblings of discontent with this trend in recent years. Economists, dismayed at rising inequality, have slowly become more favorable toward the once-maligned mid-20th-century labor movement. Some legislators have been trying to make it easier to unionize, and policymakers and thinkers have begun to consider changing the U.S. labor system in ways that would expand the reach of collective bargaining. And there was a small wave of strikes in 2018, which might hint at a labor movement that’s rising from its long torpor.

The pandemic of 2020 put a damper on that newfound enthusiasm, as workers struggled just to retain their incomes. But it might make a strong comeback in 2021. Amazon warehouse and delivery workers, frustrated by the company’s grueling work conditions, have been attempting to organize -- starting with a warehouse in Bessemer, Alabama. President Joe Biden has endorsed the Bessemer union drive, and Amazon workers around the country are now considering getting organized as well.

There's reason to think the Amazon unionization drive might be the start of a more general U.S. labor revival. Over the past decade and a half, as its warehousing and delivery operations have expanded, Amazon has gone from being a fairly insignificant employer to the country’s second-largest after Walmart Inc.

About one out of every 110 American workers are now employed by Amazon.

That could affect the labor movement in a number of ways. First of all, it gives pro-union sentiment a single high-profile opponent. As my colleagues Nir Kaissar and Tim O’Brien documented, Amazon’s public campaign against the unionization drive was particularly ham-handed. The company unleashed various proxies on Twitter to scoff at reports that Amazon workers have to resort to peeing in bottles and defecating in bags because of their grueling schedules. Muckraking journalists at The Intercept and elsewhere quickly obtained leaks from inside the company demonstrating that the practice is widespread. Meanwhile, Amazon executives’ claim that the company has great working conditions, but as Kaissar and O’Brien note, it has been fined repeatedly by the government for unsafe practices.

The sheer cartoonishness of Amazon’s anti-union public relations campaign could clarify moral perceptions around the issue — workers forced to pee in bottles going up against a megacorporation where executives make hundreds of millions of dollars a year and anti-union consultants are paid $10,000 a day.

Amazon also happens to be a big technology company in an era where big-tech companies are increasingly targets of popular ire. In 2021, 45% of Gallup respondents reported a negative view of companies such as Amazon, Facebook Inc. and Alphabet Inc.'s Google, compared to only 34% who held a positive view; this marks a sharp reversal from 2019. Most big technology companies don’t employ a lot of working-class people; Amazon, thanks to its warehousing and delivery businesses, is the big exception.

Amazon’s sheer size might help breed a sense of solidarity among the U.S. working class that has arguably been fading in the modern age. In the heyday of the U.S. labor movement, mass employment in manufacturing was the norm; “working class” could include domestic servants and agricultural laborers, but for a very large segment of the populace it meant someone who worked in a factory on an assembly line. Those workers were largely unionized.

As the U.S. transitioned out of manufacturing and into services, however, job types fragmented and proliferated. A substitute teacher, a Walmart cashier, a server in a burrito restaurant, a janitor at a contracting firm, a construction worker, a trucker and a telemarketer may all have similar income, but the work they do is so different that it might be hard to think of them as a single “working class.” Now, however, an Amazon warehouse worker or driver might become the new archetype of the American working class — the mental image of someone who endures grueling days of labor while their employer lives high on the hog.

This is all fairly speculative at this point, of course. The Bessemer warehouse’s unionization drive might fail, or other shops around the country might not join in. Or if Amazon does unionize, it might turn out to be the exception rather than the rule. The key factor might be federal policy. In the near term, the most important thing Biden can do if he actually wants to resuscitate the U.S. labor movement is to appoint strongly pro-union people to the National Labor Relations Board and other government bodies. As Ronald Reagan’s appointment of anti-union people demonstrated, the attitudes of bureaucratic personnel can have a big and lasting effect.

In an age when even many Republican voters are warming to the idea of unions, Biden could have a once-in-a-generation chance to breathe life into the dying embers of American labor power. If that happens, we might one day look back and see the Amazon fight as a turning point.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.