(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Another blowout quarter for Amazon.com Inc. earnings spurred a 10% jump in its shares in post-market trading, pushing the retail giant’s value past $1 trillion.

To gauge just how powerful Amazon.com Inc. truly is, though, look beyond its market cap, top-line sales or membership revenue and look at the so-called Amazon Tax.

This is how much the company gets from asking merchants to pay, in the form of advertising, for the privilege of being noticed by consumers.

The concept of an Amazon Tax is not new. Stratechery writer Ben Thompson talked about an AWS Tax four years ago. At that time, he was describing the e-commerce company’s cloud-services business and its membership service. And my former Bloomberg Opinion colleague Shira Ovide wrote about advertising as a toll last year.

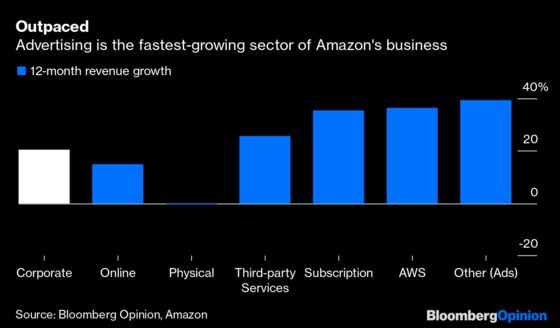

But what was once a minor category for Amazon has become its fastest-growing business. For the 12 months ended December, the revenue category it describes as “other,” which is largely ads, climbed 39%, outpacing both AWS and subscriptions for at least the fifth consecutive quarter. At its current trajectory, advertising revenue may catch up to subscriptions within two years.

The idea of a retailer leaning on advertising isn’t unique to Amazon. People often describe Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. as the Amazon of China. This is largely inaccurate. Alibaba, through its Taobao Marketplace platform, is primarily an ad-driven business.

Advertising in the retail space can be tough to pull off because companies can only make money from ads if they have enough eyeballs to sell to advertisers that want to reach them. Those with muscle, such as retail chains, often leverage their size by forcing suppliers to cut their wholesale prices. Alibaba can lean on advertising because, over two decades, it has built a ubiquitous shopping platform that sellers regard as imperative for their businesses. It also carries little of its own inventory, making wholesale discounting less of an option.

Once on the platform, vendors are told that if they want any chance of being noticed by Alibaba’s nearly 700 million Chinese customers, they’ll need to buy ads. It’s “fear of missing out” writ large. This kind of pay-for-play model has recently started working at Chinese delivery company Meituan Dianping, which turned profitable in the middle of last year thanks in large part to its ability to extract advertising revenue from food vendors.

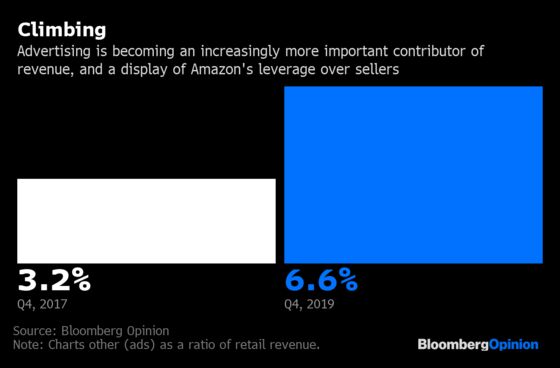

By comparison, Amazon is relatively new to the pay-for-play business, but it’s making up for lost ground. It’s also important to distinguish it from commissions, a fee Amazon takes only when it helps vendors sell a product on its site. The “other” category now accounts for 5% of total revenue, up from 2.6% two years ago. But to get any idea of its leverage over sellers, consider how much it derives from ads compared with all retail revenue. That figure climbed to 6.6% for the 12 months to December, more than double what it was two years ago.

Amazon’s ability to get customers to pay for the privilege of shopping is often seen as the strength of its platform. Recent data from Consumer Intelligence Research Partners estimates that the company has 112 million Amazon Prime customers in the U.S., accounting for 65% of shoppers in the December quarter. That’s true retail muscle.

But a real measure of power is how desperate vendors are to be noticed by those customers, and how much Amazon can extract from them to provide such an opportunity.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Tim Culpan is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering technology. He previously covered technology for Bloomberg News.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.