(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Pity the poor saps who piled into shares of Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. when it was a $750 billion behemoth and the sky still appeared to be the limit. That includes a lot of retirement savers in Hong Kong, who became involuntary investors last year when the company was added to the city’s benchmark Hang Seng Index.

By any yardstick, the timing of that inclusion was extraordinarily bad. Alibaba shares reached their lowest this week since they started trading in Hong Kong in November 2019. The stock has fallen by half since joining the index Sept. 7, 2020, and has been by far the biggest drag on the gauge. Alibaba contributed three times as much to its decline in the past year as the next-biggest laggard, Tencent Holdings Ltd., according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

That in turn has contributed to the Hang Seng Index being among the world’s worst-performing stock measures in the past 12 months. Of 92 primary indexes tracked by Bloomberg, it ranks 91st, with a decline of 7.2% for the year through Wednesday. The only worse performer is the Hang Seng China Enterprises Index — of which Alibaba is also a member.

The addition of the Chinese e-commerce company wasn’t an obvious or inevitable choice. Hang Seng Indexes Co. had to change its rules to admit secondary-listed companies and those with weighted voting rights, which it did last year after completing a market consultation. (The Hong Kong stock exchange had adjusted its own regulations to let New York-listed Alibaba sell shares in the city in 2019.)

Most global fund managers measure their performance against rival gauges, such as the MSCI China. However, the Hang Seng Index retains prominence in the Mandatory Provident Fund, the compulsory pension system introduced by the Hong Kong government two decades ago. Leading MPF providers such as Manulife Financial Corp. and HSBC Holdings Plc offer Hang Seng Index tracking funds, for example. That means investors with allocations to Hong Kong stocks will have found a portion of their retirement savings starting to go into Alibaba at just about the worst possible time.

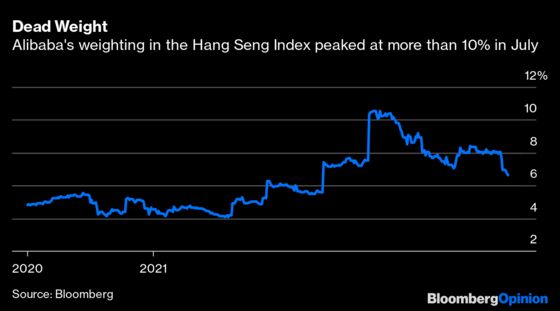

In a May 2020 press release, Hang Seng Indexes said it would cap the weighting of secondary listings at 5%. But that doesn’t appear to have lasted long. Having entered with a weighting of 4.8%, Alibaba’s peaked at 10.5% in July this year, by which time the stock had already fallen by almost a quarter, Bloomberg-compiled data show. As of Thursday, it was back to 6.8% (the index compiler said earlier this year that it would cap the weighting of any individual stock at 8%).

Does the decision deserve criticism? The Hang Seng Index needs to evolve to retain relevance, and the proposal to admit the likes of Alibaba drew overwhelming support in the market consultation. In September 2020, the internet giant was riding high: dominating e-commerce at home, expanding in Southeast Asia, and preparing for a world-record $35 billion initial public offering by its Ant Group unit. Who could have foreseen that within weeks, China’s government would scuttle the IPO, banish founder Jack Ma from public view, and turn Alibaba into one of the primary targets of its anti-monopoly and “common prosperity” drives?

“The HSI has not gone anywhere over the last few years even as other indices have moved up a lot over the same period,” Brian Freitas, an analyst who publishes on Smartkarma, said in an email. “The expectation was that these companies and their stocks would do well, the index would move higher and there would be more assets benchmarked to these indices (which is one of the ways that Hang Seng Indexes makes money).”

We have the benefit of hindsight. Still, there was nothing compelling Hang Seng Indexes to act with such haste — moving to admit a company that wouldn’t normally have been eligible just at a peak of investor enthusiasm. The HSI advisory committee has full discretion on which stocks to include or delete from the index, Freitas pointed out. That’s unlike other global indexes that are mainly rules-based.

Index compilers shouldn’t try to be market-timers. It wouldn’t have hurt to wait. Hong Kong’s future retirees, at least, would have thanked them.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Matthew Brooker is a columnist and editor with Bloomberg Opinion. He previously was a columnist, editor and bureau chief for Bloomberg News. Before joining Bloomberg, he worked for the South China Morning Post. He is a CFA charterholder.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.