After the Virus, Can the EU Seize Its ‘Hamilton Moment’?

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- As the coronavirus pandemic continues, Bloomberg Opinion will be running a series considering the long-term consequences of the crisis. This column is part of a package on monetary policy. For more, see Clive Crook on the end of central bank independence, Dan Moss on Asia’s growing influence and Mohamed El-Erian on creating a sustainable recovery.

Around the world, central banks have been forced to take dramatic action thanks to the Covid-19 pandemic. After a slow start, the European Central Bank has been one of the most ambitious. In mid-March, it adopted a wide-ranging package, including a major asset-purchase scheme with far fewer restrictions than it imposed in previous rounds.

Such a program was necessary to preserve the stability of the euro area. But it raises long-term questions about the future of monetary policy and of the euro itself. The fear is that the central bank will face excessive constraints once the outlook stabilizes and the emergency subsides.

With some prudence and forethought, however, this crisis could also offer a once-in-a-generation opportunity to undertake the reforms necessary to not only manage rising debt loads, but to place the entire European project on a firmer footing. What steps policy makers take once the immediate crisis passes will make all the difference.

*****

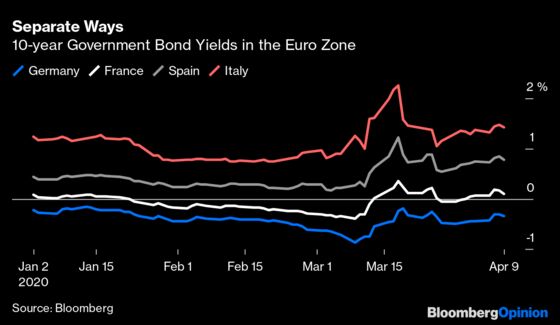

By any measure, the ECB bungled its initial response to the outbreak. As late as Feb. 21, Philip Lane, the central bank’s chief economist, was saying that he expected a “V-shaped” recovery, implying that the bank saw little need for imminent action. ECB President Christine Lagarde was the last among the chairs of the major central banks to promise intervention if needed. Then she made a serious error when she told reporters that the bank would not act to close spreads between government bonds in the monetary union. The yields of fragile countries such as Italy soared, prompting fears of a new sovereign-debt crisis.

Thankfully, the ECB soon bounced back. A few days later, Lagarde announced a “Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program” (or PEPP), a temporary $820 billion scheme involving both government and private debt. This was no ordinary quantitative-easing program. For one thing, it included Greek sovereign debt, which had been deemed too risky for inclusion in previous rounds. It also allowed the ECB to allocate purchases as it saw fit and dropped the bank’s self-imposed restrictions on how much of a country’s debt it could buy. Finally, Lagarde announced that the bank had “no limits” on its commitment to the euro area.

Taken together, these steps meant that the ECB could direct its firepower at the most vulnerable countries, and it has followed through. In just the first three weeks of the program, the bank purchased more than 50 billion euros in assets, focusing on the countries that needed most support. The impact on financial markets has been sizable: The yield on Italy’s 10-year bonds has dropped from nearly 2.5% in mid-March, to about 1.7% in mid-April. Italy’s spread with Germany’s 10-year bonds has narrowed from nearly 280 basis points to less than 220.

The ultimate success of PEPP, however, will depend on the length and depth of the economic crisis, which in turn hinges on how long and severe the epidemic will be. For now, the signs are extremely worrying.

*****

Most European economies have imposed draconian lockdowns, which in Spain and Italy have extended to all non-essential activities. These restrictions are hitting the services sector particularly hard. The Purchasing Managers Index for the euro area plunged to 26.4 in March, down from 52.6 in February. In Italy, it fell from 52.1 to 17.4, the lowest reading ever recorded.

Although many countries have started to plan how and when to reopen some businesses, normalization will be hard. Among other things, scientists don’t yet know how long a recovered Covid patient will be immune to reinfection. It’s also very unlikely that countries are close to “herd immunity.” The best hope is a vaccine, but even optimistically this will take 12 to 18 months to produce and distribute, assuming one can be found.

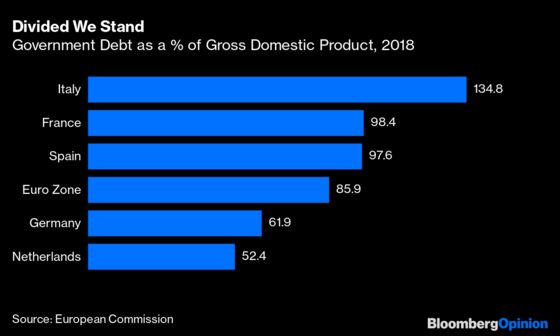

The ECB may therefore have to remain active for some time. Worse, countries will reemerge from the crisis with much higher levels of debt. Greece, Italy and Portugal have already incurred debts exceeding 100% of gross domestic product. Were the crisis to add, say, 20 or 30 percentage points to these piles, investors would surely question their sustainability. This suggests that the bank’s aggressive support will be needed long after the epidemic has ended.

The ECB hasn’t yet specified what it will do with the sovereign and corporate bonds it will accumulate under PEPP. In theory, it could seek to shrink its holdings as soon as the crisis is over. More likely, though, it will retain them for an extended period. The ECB’s mandate is to keep inflation below but close to 2%. Yet the pandemic may have strong deflationary effects, as companies struggle to sell their goods and workers accept lower wages to keep their jobs.

This suggests the ECB will roll out a program of reinvestments, just as it did after its previous rounds of asset purchases, which would allow it to continue pushing down interest rates and hence stimulating the economy, even after it has stopped adding new debt to its balance sheet.

In that case, the ECB will likely face one of two problems — both of which policy makers must now be preparing for.

*****

For a start, there’s the risk that inflation remains too low, or even negative, for a prolonged period. The euro area could start looking like Japan, which has been stuck in deflation for the better part of two decades. The ECB would then likely continue adding to its debt holdings, but monetary policy would have very little impact on inflation.

The second and opposite problem is that inflation returns. At that stage, the ECB would need to raise rates to comply with its mandate, even though this would put pressure on vulnerable countries with very large public debt. A rise in inflation rates could coincide with a return of economic growth, which would help to make debt levels more sustainable. But it could also result from a supply-side shock, or because Europe’s economy picks up mainly in the regions with the lowest debt levels. In that case, by raising rates, the ECB would be undermining financial stability.

One way or another, the euro area will have to decide what to do about the excess debt that will be accumulated during the pandemic. One radical option would be for the central bank to monetize it. However, this is illegal under EU treaties and it is very unlikely that member states will agree to a change of that magnitude.

This leaves three options:

- A sizable wealth tax. This would be relatively straightforward, since it would be decided and imposed nationally. However, it could further depress the economy after years of crisis and could lead to capital flight.

- Debt restructuring. Although this would spread the burden among all creditors — foreign and domestic — it would have a knock-on effect on the banking sector, which still holds large amounts of government debt.

- Debt mutualization. This could be achieved through (say) a joint debt-reduction fund, which would make all euro-area member states responsible in joint-and-several fashion for a portion of their debt. But it would face major legal hurdles, since EU treaties do not allow one member-state to bail out another.

Legal obstacles aside, though, this final option could reduce the risk of financial instability by removing some of the burden from those with the weakest shoulders. Crucially, it could also create a pan-European safe asset, which banks could then use in the same way as their American counterparts employ Treasuries.

*****

Which brings us to the opportunity that this crisis presents. The issue of debt mutualization may sound technical, but it is, above all, political — with significant consequences for the future of the EU itself.

To be sustainable, the euro area needs to graduate one day into a fully fledged fiscal union, with a common treasury endowed with its own taxing and spending powers. It needs, in other words, a “Hamilton moment,” mirroring the agreement reached by U.S. Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton in 1790 to assume the Revolutionary War debts of the various U.S. states, thereby binding them more tightly to the federal government and stabilizing the country’s finances.

Any similar advancement of the European project will require devolving some income streams to Brussels, and setting up tougher enforcement rules to ensure that member states don’t act as free-riders. Neither is easy. But it will also require a more helpful narrative: At the moment, fiscally strong states such as the Netherlands and Germany don’t want to take on debts that have been accumulated as a result of sheer fiscal mismanagement. A debt-reduction fund limited to sharing the costs of the Covid-19 pandemic would minimize this political problem. After all, the virus is no one’s fault. As such, it could be a useful stepping stone on the road to broader and deeper economic and political integration.

The future of the EU may therefore depend on what actions governments decide to take after the pandemic. The ECB is doing all it can to reduce the pressure at a time of crisis. But Lagarde will surely be hoping that political leaders return the favor afterward.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Ferdinando Giugliano writes columns on European economics for Bloomberg Opinion. He is also an economics columnist for La Repubblica and was a member of the editorial board of the Financial Times.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.