Lincoln Broke the Constitution. Let’s Finally Fix It.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- As Republicans develop a strategy for the 2022 and 2024 elections, expect them to borrow at least one trick from the playbook that Glenn Youngkin used to win the 2021 Virginia governor’s race: tar Democrats with the brush of “critical race theory.” Almost no one can say exactly what CRT is, but that doesn’t seem to have mattered last month in the northern Virginia suburbs, where the Republican made inroads among Democrat-leaning voters.

The attack on CRT is a proxy for a vulnerability that Republicans correctly see Democrats as having. The consciousness-raising of Black Lives Matter and a new focus on the legacy of slavery has left the party flailing. Democrats — and progressives and liberals more generally — find themselves without a coherent narrative about race in American history, or one that Americans of all races can embrace.

They are vulnerable to the charge that they have adopted what is sometimes called Afropessimism, the view that the slavery present at the American founding created an unchanging and unchangeable fundamental structure of White supremacy and racism that can never be eliminated or improved on.

Democrats can’t go back to whitewashing the story of American origins, as most White Americans have long done. And they can’t embrace an account of race that leaves no room for progress, amelioration and the moral arc of history that the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. preached and President Barack Obama affirmed.

The solution is to develop a new narrative, one that is historically accurate and also leaves room for the possibility of future improvement.

That narrative must deliver honesty about slavery in the Constitution of 1787. It must highlight and celebrate the breaking and repudiation of the slave Constitution by President Abraham Lincoln and the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments. It must acknowledge the betrayal of the equal-protection promise in the era of segregation — and the revival of that promise through the efforts of the Civil Rights movement and the enactment of the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act. Americans can acknowledge both the wrong of the past and efforts to reverse those wrongs. Doing so will make the U.S. a better nation, and a more unified one.

Democrats have no way of sidestepping the need to settle on a unifying narrative about race, history and the national future.

The party relies on turnout from Black voters, and those voters need to know what the party believes about race.

It needs White voters, too, and they also care about race in American history. White Americans, regardless of political affiliation, now acknowledge the reality of slavery and segregation, even if only to insist that they are now in the past. The question is what to make of that history, and what collective meaning to assign to it.

‘We the People’

The distinctive way that Americans talk and think about the Constitution helps explain why the historical narrative about race matters so much. As written, the Constitution purports to unite “We the People” in a common collective project of self-governance that stretches across time. To sustain a sense of that collective consciousness, the meaning of “We the People” circa 1787 needs to be defined.

The first crucial truth that must be told about the Constitution is that it entailed a compromise between Northern and Southern Whites over the question of slavery. The Constitution guaranteed that Congress would not eliminate the international slave trade for 20 years. It counted each enslaved person of African descent as three-fifths of a human being. Through the fugitive slave clause, it enshrined the principle that free states would recognize the constitutionality and legality of slavery by returning escaped slaves to their masters.

Some of the framers were embarrassed by these compromises, which is why the Constitution didn’t use the word “slavery,” but instead adopted euphemisms like “persons held to service or labor” and “other persons.” On this flimsy basis, some defenders of the Constitution have argued since the 19th century that the original document didn’t actually recognize the institution of slavery.

In the past, that view was mostly adopted by people who knew it was historically false but wanted, for excellent political reasons, to enlist the Constitution on behalf of opposition to slavery. That included a minority of abolitionists.

Frederick Douglass, who began his career condemning the Constitution as a proslavery document and later described it as self-contradictory, ultimately settled on this argument. He knew that the Constitution of 1787 was not antislavery as drafted or intended, but concluded, reasonably, that if he wanted to convince White Americans that slavery was wrong, he would be better off enlisting the Constitution than condemning it.

Today, it’s impossible to maintain seriously as a historical matter that the original Constitution did not embody a compromise that recognized slavery. The fugitive slave clause of Article IV is, legally speaking, the most explicit conceivable recognition of the validity of slavery. It was intended to require Northern states to extend formal constitutional or legal recognition to the status of slavery — and it did so, both in practice and in theory.

In 1772, in a landmark British case called Somerset v. Stewart, the Court of King’s Bench in London had held that an enslaved person brought to England from the colony of Jamaica became free on arrival in the mother country, because the laws of England contained no positive recognition of slavery. Under this legal principle, escaped slaves who reached free states could have argued that they must be declared free.

The framers knew this case. The fugitive slave clause was intended to repudiate the doctrine as applied to the U.S., at least with respect to escaped persons who fled on their own. Courts in the Northern states upheld the clause as binding law, thus recognizing that the Constitution considered slaves to be the property of their Southern masters even when they managed to make their way to free states.

An honest account of slavery in the Constitution of 1787 must admit that American slavery was based on a theory of White supremacy. It follows, painful though it may be to acknowledge it, that the original Constitution recognized and upheld a worldview that today is rightly considered repugnant.

It’s understandable that White people raised in a political culture that venerates the framers would not want to admit that the Constitution they drafted and ratified was so morally flawed. But they should also grasp the difference between childhood worship of parents as ideal beings, and adulthood, when recognition of parental limitations requires loving them no less. It’s high time for the U.S. to enter adulthood with respect to attitudes toward political progenitors. Americans can continue to honor the debt to them while recognizing things they did that were wrong, even when judged by the standards of their own times.

Breaking the Constitution

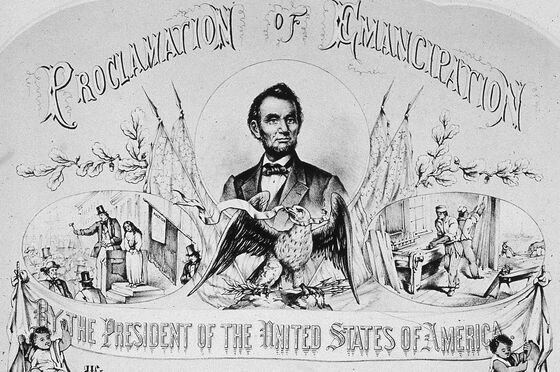

The next, crucial step of the new narrative must focus on the moment when the Constitution broke, and was broken. Every American today understands that the Confederate states broke the Constitution when they seceded from the Union. What is less well understood is that Lincoln also broke the Constitution by emancipating enslaved people in the Confederacy.

He didn’t do it right away, as a swift response to secession in 1860. It took a year and a half from the beginning of his presidency the following year — when he had publicly committed himself to preserving slavery as guaranteed by the Constitution — for him to announce his plans for the Emancipation Proclamation, which was not issued until Jan. 1, 1863. When he did that, however, Lincoln changed the fundamental terms on which the Union was organized.

The original Constitution was based on a compromise that preserved slavery. By emancipation, Lincoln proclaimed that the compromise would never be restored, even if the Union won the war and reasserted sovereignty over the former Confederate states. This act of epochal historical significance was then followed by the enactment of the Reconstruction amendments. Those amendments ended slavery everywhere (13th); guaranteed equal protection of the laws for all (14th); and enfranchised African-American men (15th). They were, and are, the basis for the Constitution we have today.

The Constitution created by the Civil War and the Reconstruction amendments is not the same Constitution as the one signed in 1787. The first Constitution was tainted by slavery. The second Constitution was cleansed of that taint. The first Constitution rested on a compromise that even many supporters knew to be immoral. The second Constitution embodied, and still embodies, a set of moral aspirations to equal liberty for all.

It would be convenient if the narrative could stop there, but it can’t. It must then acknowledge another painful truth, which is that the promises of the new, moral Constitution were betrayed by the ending of Reconstruction and the willingness of Northern Whites to allow Southern Whites to impose legal segregation and disenfranchisement on Blacks. (De facto segregation existed in the North as well, and shouldn’t be left out of the story.) For an astonishing three-quarters of a century, the promises of the 14th and 15th amendment were evacuated of meaning. Slavery itself was not reinstated, but systemic segregation and disenfranchisement left many Black people in circumstances that were little better than the old system.

It took Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 and a decade of intense, brave, noble efforts by the civil rights movement to overturn this dark period of constitutional betrayal. Crucially, the narrative must recognize the truth that Black people demanded and obtained legal equality through the civil rights movement. The hard-earned victories of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 represented the vindication of the post-Civil War Constitution, every bit as much as the Civil War represented the repudiation of the Constitution of 1787.

Flaws of the Founders

The last part of the new narrative is probably the most delicate. The triumph of the civil rights movement, now acknowledged by Martin Luther King Day and by a plethora of civil rights memorials and museums built in the last few decades, did not transform the U.S. into a society where people are economically and socially equal regardless of race. The way to acknowledge this truth is by saying bluntly that equality before the law is not the same as real-world equality.

American faith in the Constitution is valuable as a potential tool of unification. Yet it shouldn’t replace the understanding that no legal document, not even a reconstructed Constitution, is self-executing — that writing lofty principles into law does not transform them into reality.

Breaking and then remaking the U.S. Constitution gave the values of equality, liberty and opportunity the legal weight they deserved after four score and seven impoverished years. But it didn’t erase the result of centuries of slavery followed by segregation that continues to constrict the prospects of Blacks compared to those of White Americans.

That brings us back to the narrative needed today, in the Virginia suburbs and beyond.

The first Constitution could not be repaired except by war, and equal protection could not be established except by force. Today’s Constitution, by contrast, now expresses the high American values that were not included in the original.

Another war shouldn't be needed to vindicate those values. Like the legislative victories achieved by the civil rights movement, the progress we need now can be accomplished by the political process via a common commitment to achieving fairness.

The story of our constitutional past makes it clear that, even today, Americans of different races, on average, don’t start life with equal resources. The impact of slavery and segregation didn’t end just because the legal regimes that created them passed away. Legal equality is an important step along the way to economic and social equality. But it’s just a step.

The solution is public investment in the inputs available to Americans disadvantaged by past inequality; actual assets that can be used for education, housing and entrepreneurship. Those could be conferred on Americans who can show that they are descended from people who suffered from slavery and segregation, and that they remain less well-resourced than the average American who does not share that inter-generational experience. Framed in terms of fairness within the capitalist system, not as reparations or affirmative action, that program would represent progress that many Americans should be able to embrace.

Thus, honestly acknowledging the flaws of the founders, and then celebrating Lincoln's generation and King’s, can be seen as a step toward establishing not only a common understanding of what happened but also a common understanding of what's needed. Honesty about the past should make it easier to be honest about the present. And honesty about the present can underwrite a political program for a future in which the U.S. can make genuine efforts to overcome the inequality that still exists.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Feldman is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist and host of the podcast “Deep Background.” He is a professor of law at Harvard University and was a clerk to U.S. Supreme Court Justice David Souter. His books include “The Three Lives of James Madison: Genius, Partisan, President.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.