(Bloomberg Opinion) -- For as long as I’ve been an economics journalist (23 years, more or less), the mainstream view among economists has been that taxing capital — corporate profits, dividends, capital gains, savings and wealth in general — is:

- Counterproductive, because capital investment fuels productivity gains and economic growth, and

- Usually futile, because capital owners have so many ways to avoid taxes and shunt the burden onto others.

The former argument has undeniably lost a little of its oomph in recent years. The influential papers that implied that the optimal rate of capital taxation is zero (Atkinson and Stiglitz, 1976, Judd, 1985, and Chamley, 1986) have been contradicted by new theoretical models. There is some empirical evidence that high corporate income tax rates in particular may be a drag on growth, and this was one of the main justifications for the big reductions in corporate and other business taxes contained in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. But the case against capital taxation is no longer quite the slam dunk that it seemed like a couple of decades ago, in part because there is so obviously not a shortage of capital at the moment.

Argument No. 2, meanwhile, is the main target of the new book by economists Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman that has been dominating economic-policy talk for the past few weeks. This is not the aspect of “The Triumph of Injustice: How the Rich Dodge Taxes and How to Make Them Pay” that has gotten the most attention so far, with debate focusing mainly on Saez and Zucman’s advocacy of wealth taxes and their depiction of the progressivity (or lack thereof) of the U.S. tax system. But what stood out most to me about the book was its authors’ simple refusal to accept that corporations and the wealthy cannot be forced to pay up. It is a bold assertion of the primacy of politics over economics, and while I’m not sure I want to buy all the tax solutions that Saez and Zucman are selling, this aspect of their argument is both refreshing and, most likely, a sign of things to come.

Saez and Zucman are professors at the University of California at Berkeley, and frequent collaborators of Paris-based economist Thomas Piketty, whose 2013 book, “Capital in the Twenty-First Century,” did much to focus global attention on economic inequality. Earlier research by Piketty and Saez used data from the Internal Revenue Service to identify previously unexamined trends in the higher reaches of the income distribution in the U.S., popularizing the term “the 1%” even while revealing the more spectacular income gains made by the top 0.1% and 0.01%. Zucman, the youngest of the trio, has focused mostly on tax evasion and tax havens, establishing a reputation as, to quote the headline on a Bloomberg Businessweek cover story from May, “The Wealth Detective Who Finds the Hidden Money of the Super Rich.”

This has gotten easier to do lately thanks to the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, passed by Congress and signed into law by President Barack Obama in 2010, which requires foreign banks to report accounts held by Americans to the IRS or face tax penalties in the U.S. Bank secrecy in Switzerland and elsewhere was seen as a fact of life, and a big reason why it would be hard to enforce any kind of wealth taxation. Then it was gone, at least partially. “What’s been accepted yesterday can tomorrow be outlawed,” Saez and Zucman write in reference to FATCA.

Another such change is the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s recent effort to rein in corporate profit shifting across national lines, which has resulted in requirements that multinational corporations report their country-by-country profits and tax payments to tax authorities. As a result, Saez and Zucman argue, countries are now able to insist that their corporations pay tax at a minimum rate (“say 25%”) even if they’ve shunted income through low-tax jurisdictions:

Any country can in effect serve as the tax collector of last resort for its multinationals. Apple pays 2% in Jersey? The United States could collect the missing 23%. The Paris-based luxury group Kering books profits in Switzerland, taxed at 5%? Paris could levy the missing 20%.

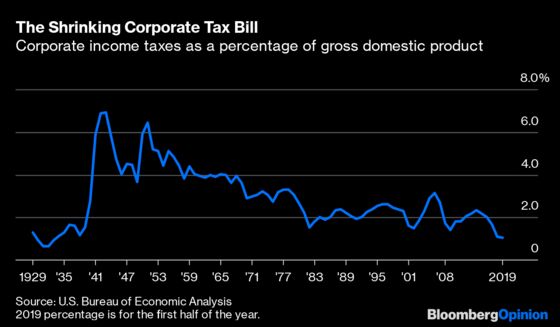

The 2017 tax bill actually includes just such a provision, albeit at a lower rate than Saez and Zucman envision: 10% now, and 12.5% in 2026 and beyond. With the regular corporate tax rate now at 21%, this means there are still ample rewards to manufacturing “stateless income” that escapes most taxation, something that large U.S. tech companies in particular have mastered. And overall, the U.S. corporate tax burden is now lower, as a share of gross domestic product, than it’s been since the Great Depression.

While corporate income taxes have fallen, the total local, state and federal tax burden in the U.S. is somewhat higher now than it was in the 1950s. The burden hasn’t gone away, it’s just been shifted.

There is a rich economic literature on the “incidence” of corporate taxes, with some arguing that, because workers have fewer options for avoiding taxes than corporate shareholders do, they bear the bulk of the burden. Saez and Zucman are — surprise! — dubious of this reasoning.

Contrary to what many ideologues would like you to believe, economics has not “proven” that workers “bear the burden” of the corporate income tax. If this were true, then unions all over the world would be begging governments to slash it. In the real world, the most vocal proponents of the view that ordinary workers — not wealthy shareholders — suffer from high corporate taxes are … wealthy shareholders.

They have a point there. What’s more, better enforcement ought to reduce the ability of those wealthy shareholders to shift the corporate tax burden onto workers. It’s a win-win.

Corporate income taxes do have some other issues. Even if they fall mainly on shareholders, who tend to have high incomes, they can’t be calibrated to impose progressively higher rates on higher incomes in the way that individual income taxes can. Taxing corporate income as well as the capital gains and dividends that corporate shareholders receive also amounts to double taxation that can distort economic behavior. Saez and Zucman see corporate income taxes more as a backstop than the main event, and they favor avoiding double taxation by giving shareholders credit for the taxes that corporations pay. They also think capital gains taxes should be indexed to inflation to avoid the “opaque and random type of wealth tax” that unindexed capital gains taxes represent.

Other kinds of wealth taxes are fine by them, of course, and there is much to debate about their proposals on that front. There’s also room for debate over whether targeting just the top of the income and wealth distribution in the U.S. can really raise enough money to meet the country’s future needs.

There really shouldn’t be controversy, though, over whether corporations and the very wealthy should be allowed to take advantage of globalization and tax havens to avoid paying taxes. Yet there has been controversy, or at least a lot of fatalism. After consulting economists, tax experts and government officials from multiple countries on corporate taxation in late 2018, the International Monetary Fund reported that “many respondents and interlocutors noted that tax competition is likely to intensify.” Which inspired this retort from Saez and Zucman:

Contrary to what the experts polled by the IMF may believe, globalization does not prevent countries from taxing corporations at high rates. Those who profess that the race to the bottom in corporate income tax rates is natural, that imposing sanctions against tax havens is a crime against free trade — they are not the defenders of globalization. What will make globalization sustainable is not the disappearance of capital taxation, but its reinvention.

Again, I think they have a point. They also have U.S. public opinion solidly on their side. It has been much remarked lately that most Americans, in contrast to many in the policy elite, are quite supportive of higher taxes on the very wealthy. But do you know what seems to be even more popular, and has been for decades? Higher taxes on corporations.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Sarah Green Carmichael at sgreencarmic@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.