From Aristocracy to Meritocracy: the Revolution in Britain’s Top Schools

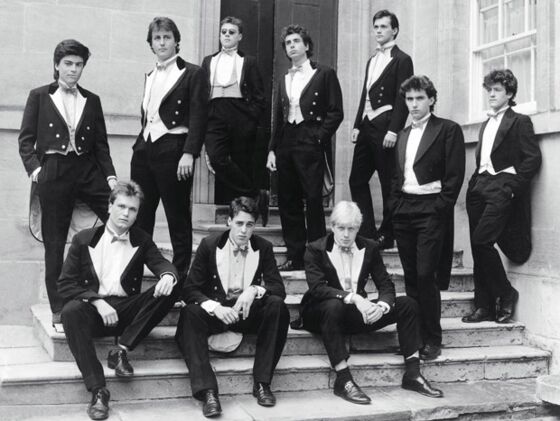

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The photograph that is most closely associated with Oxbridge shows ten young men in 1987, dressed in white tie and tails, staring at the camera with all the floppy-fringed arrogance they can muster. These are the members of the Bullingdon Club, Oxford’s most exclusive dining society: a clique whose members have been wrecking local restaurants and vomiting in local flower beds since the 1780s. Two of the young men in the photograph went on to become prime minister, David Cameron and Boris Johnson.

Yet perhaps a more appropriate photograph is one that was published on Monday. This shows 89 young men and women — the vast majority of them from ethnic minority backgrounds — standing outside Brampton Manor Sixth Form in the London Borough of Newham. Their faces are wreathed in smiles but there is not a touch of arrogance about them. If they feel that the world is at their feet, it is because they have worked hard, not because they were born to rule. These students have all been given conditional offers to study at Oxford and Cambridge universities.

Nowadays, Brampton Manor Academy regularly gets as many pupils into Oxbridge as Eton College, the alma mater of Cameron, Johnson and the majority of the privileged faces staring out from the 1987 photograph. It does this by dint of high-expectations and relentless discipline. Pupils arrive early in the morning and stay on into the evening in order to accumulate extracurricular activities. Slacking is not tolerated. Pupils are expected to be smartly dressed and always on the ball. Eton — the quintessential, privately-funded British public school — charges about £50,000 a year and selects from the whole world. Brampton Manor charges nothing and selects from one of the poorest boroughs in London. The majority of pupils are from ethnic minorities and one in five gets free school lunches because of their parents’ low incomes.

Though Brampton Manor is an unusually successful institution, it is not alone. Across the country Academy schools — free from local government control and empowered to select on academic ability in the sixth form, usually pupils aged 16 to 19 — are producing first-rate academic results. In the East End of London alone, Brampton is one of three — the others being the London Academy of Excellence in Stratford and Mossbourne Academy in Hackney — that collectively send hundred pupils to Russell Group universities, the U.K.’s elite 24 schools of higher learning.

The result of this welling up of excellence is that Britain’s elite education sector is changing fast. Oxbridge is becoming less of a playground for the Bullingdon boys and more of a multiethnic meritocracy. In 2020, almost 70% of Oxford students came from state schools, the highest percentage in the 700-year history of the University. In 2010, when Cameron — the first of the Bullingdon prime ministers in that famous photograph — came to power, the figure was about 54%, barely more than half despite the fact that state schools educate 93% of the population. A similar revolution is going on in Cambridge and other Russell Group universities.

The Tory Party’s favorite slogan when it comes to social policy is “levelling up”: a much-criticized (or perhaps nitpicked) attempt to close the gap between the north and the south. But, whatever is going on when it comes to “levelling up,” another big change is also underway: The U.K. is beginning to close the meritocracy gap.

Britain has always been notorious for the yawning chasm separating the social classes: between the towering toffs who were born to rule and the shrunken proles who were born to serve them (and pronounce their ‘aitches). But in more recent decades, another gap has taken the place of the older one — or perhaps been superimposed upon it. The credential gap between the exam-passing and the exam-flunking classes.

The traditional rich have embraced meritocratic values. For all his aristocratic affectations, Johnson was in fact a scholarship boy at Eton and then at Balliol College, Oxford. At the same time, the new rich who made it in the go-go days of the 1980s and 1990s have tried to consolidate their position at the top of society by sending their children to private schools (that is, those privileged public schools like Eton and Harrow) or buying houses near first-class state schools. The result was the formation of a composite meritocratic-plutocratic elite at the top of British society that hogged all the best jobs.

The 1944 Education Act — with its vision of a tripartite school system divided into grammar schools, technical schools and an exam system that sorts pupils by academic merit from the age of 11 — had been designed to prevent any such hogging from happening and to produce a truly mobile and meritocratic society. And for a while it looked as if it was succeeding. The public schools’ share of Oxbridge places declined from 55% in 1959 to 38% in 1967, with the difference made up almost entirely by grammar school pupils. The proportion of eldest sons of peers who gained admission to the two ancient universities declined from nearly 50% in the 1950s to 20% in the late 1960s. William Waldegrave, who went up to Oxford in the late 1960s and is now provost of his old school, Eton, noted that the new grammar school boys and girls were cooler than his public school counterparts. “They were confident, clever and at last as widely cultured as we were… a surge of new, meritocratic ability refreshed Britain…”

This brave new world was destroyed by the Labour Party’s conversion to equality of results rather than equality of opportunity. Two powerful secretaries of state for education, Anthony Crosland (1965-67) and Shirley Williams (1967-69), both of them products of private schools, set about abolishing grammar schools and direct grant-schools (which provided subsidies for poor students to go to fee-paying schools) in the name of levelling the playing field. The new comprehensive schools they created in turn adopted mixed-ability and progressive teaching methods on the grounds that, if the 11+ exams couldn’t be relied on to sort out children accurately, then the same would go for every other test. This happened at exactly the same time that private schools embraced academic excellence in the name of modernization.

I have vivid memories of the impact that this double revolution had on Oxford during my own time there. In 1977, the tone of the university was set by grammar school types, and the Etonians were a defensive clique who kept themselves to themselves. By the mid-1980s, however, when I was completing my D.Phil. the number of public-school pupils was rising once again and the Bullingdon boys (and their paramours) were back on top. I remember seeing a young Boris Johnson striding through the front quad of Balliol as if the world was his oyster and the prime ministership as good as in the bag.

The push back against this anti-meritocratic revolution began in the 1980s. Margaret Thatcher encouraged schools to compete for pupils, and her successor as prime minister, John Major, published league tables of school performance. But the great breakthrough came later under Tony Blair and then David Cameron. In the Blair years, Andrew Adonis, the head of the policy unit at No. 10 Downing Street, and Michael Gove, the Secretary of State for Education, pursued reforming agendas. The result was a revolution — or rather a counter-revolution — that can be seen in the 89 faces caught in the Brampton Academy photograph.

Britain’s progress in closing the meritocracy gap needs to be applauded. The country is finally moving in the right direction after decades in which it was moving in the wrong one. But much more needs to be done: after all, 30% of Oxbridge students still come from schools that educate 7% of the population and large swathes of the country don’t have any high-performing schools. Academies should be allowed to select for intellectual promise at the age of 11 rather than having to wait until 16. It is absurd that such schools can select for promise in drama or music or sport at the younger age but not for brain power. Direct-grant schools should be reinstated. The reintegration of great northern schools, such as Manchester, Leeds and Newcastle Grammar Schools, into the state system would advance levelling up as well as helping to close the meritocracy gap.

Above all, public schools should be restored to their original purpose. Winchester and Eton and their later imitators were originally created to provide free educations for “poor and needy scholars” who would go on to work for the church or the state — which is one reason why they enjoy charitable status. But today they provide expensive educations for the children not only of British plutocrats but of foreign ones as well, not least Russian oligarchs. The Independent Schools Council reported in 2019 that just 1% of private school pupils had all their fees paid for by their schools and just 4% had more than half their fees covered. More than a third of the boarders at elite public schools were born abroad.

During the Second World War, Winston Churchill, a proud Old Harrovian, concluded that the public schools could only survive if they compromised with the meritocratic spirit of the times and gave away 60% to 70% of their places to poor scholars who received grants to study based on need. The least that the Churchill-admiring Johnson can do to make amends for that dreadful 1987 photograph of toffish entitlement is to oblige schools to give half of their places away for free and pay for them out of their gigantic (and tax-free) endowments. That way, the meritocratic revolution that is gathering pace so splendidly will finally be completed.

More From This Writer and Others at Bloomberg Opinion:

- Can You Afford to Join the Great Resignation?: Stuart Trow

- America Is Facing a Great Talent Recession: Adrian Wooldridge

- The Anti-China, Pro-Immigration Coalition: Matthew Yglesias

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Adrian Wooldridge is the global business columnist for Bloomberg Opinion. He was previously a writer at the Economist. His latest book is "The Aristocracy of Talent: How Meritocracy Made the Modern World."

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.