A $33 Billion SPAC Deal Looks Even Stranger Up Close

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Before property developer Ophir Sternberg began exploring a $33 billion deal to take trial lawyer John H. Ruiz’s health-care litigation firm MSP Recovery public, the pair discussed a very different transaction: the purchase of Sternberg’s condo at the Ritz-Carlton Residences, Miami Beach.

The terms of the real estate sale they agreed on, which include a possible exchange of MSP shares for monies Ruiz owes to Sternberg, are detailed in a prospectus published last week by Sternberg’s special purpose acquisition company, Lionheart Acquisition Corp II, ahead of its merger with MSP.

I’ve looked forward to reading that document ever since the eye-popping SPAC deal was first announced in July and Bloomberg News unpicked its many oddities, which encapsulate the problems people associate with SPACs. At the time, one prominent investor said the deal gave the whole SPAC asset class “a bad rep.”

Founded in 2014 and now with around 80 employees, MSP seeks to identify instances where the wrong health-care payer has been billed. After acquiring those claims, it tries to recover the money through the courts from insurers who should have paid. My colleague Matt Levine called the enormous price tag “psychological anchoring,” while The Financial Times asked: “Can this US healthcare litigation company really be worth $33 billion?”

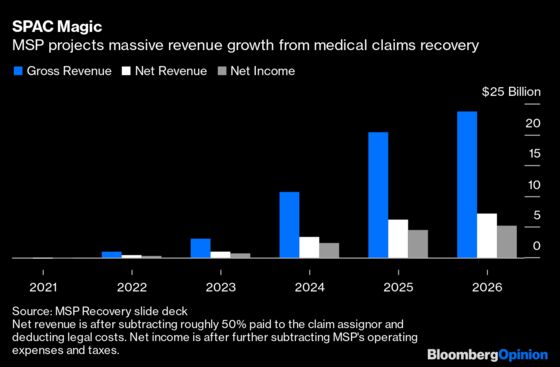

It’s a fair question and the prospectus doesn’t inspire much confidence. MSP hasn’t generated meaningful revenue yet.

I’ve often worried that in their desire to complete deals and secure lucrative compensation, sponsors don’t aggressively negotiate the deal price. Targets are fine with this, of course — they’d rather agree on the value with the SPAC rather than leave it to an unpredictable IPO process. They tend to rely on optimistic financial projections to justify their prices, which generally isn’t possible when going public the traditional way. Plus, unlike in a regular IPO, there’s no underwriter with liability for what appears in the merger prospectus. No wonder the post-merger performance of SPAC deals is often disappointing.

Litigation finance is booming, but at more than 30 times the net revenues MSP anticipates in 2023, its purported valuation is certainly ambitious. After contributing at most $160 million to the merged company , SPAC shareholders will end up owning less than 1% of MSP, while more than 90% will remain with Ruiz and his business partner.

In an interview, Ruiz told me the $33 billion valuation reflected the strength of the company’s current claims portfolio, future claims and financial model, and was the result of months of negotiations and “a lot of due diligence.” On why MSP hadn’t yet generated substantial revenue, he explained that “legal cases in the United States take a significant amount of time.”

So how does the deal value relate to rivals? “Traditional benchmarking metrics, such as comparable transactions, or the trading prices of comparable companies, were unavailable to this transaction, given that MSP is essentially a missionary company, helping to establish a new category of business enterprise,” the prospectus notes, rather unhelpfully.

It’s worth noting that Lionheart did not seek a fairness opinion (a third-party evaluation) nor did it secure an institutional PIPE investment (a separate pot of institutional money typically announced in conjunction with a SPAC transaction), both of which might have helped validate the agreed-upon transaction price to the outside world.

A Lionheart spokesperson told me that fairness opinions aren’t required and the vast majority of SPACs don’t seek them, that MSP didn’t have any immediate need for PIPE money to fund the business post-merger and that Lionheart’s officers have “substantial experience” in evaluating companies from a wide range of industries. The transaction was unanimously approved by Lionheart’s independent directors “after numerous board meetings” and “careful consideration.”

Nevertheless, the prospectus includes a standard warning that absent such external validation, “investors will be relying solely on the judgment of the [Lionheart] board in valuing MSP’s business, and assuming the risk that the [Lionheart] board may not have properly valued such business.”

The prospectus points to other grounds for circumspection, especially regarding investors cashing out early. An external investor that funded MSP claims could receive a more than $600 million dividend within one year of closing which may be paid via share sales. MSP’s current owners are also permitted to sell as much as 10% of their shares after the merger closes. Ruiz said he’d structured the deal this way, instead of taking cash out immediately at closing, because “we are firm believers in the company.” However, a high volume of share sales, if that should happen, could depress the stock price.

Some of the related-party transactions also raise some eyebrows. Some 20% of the gross revenues generated from MSP’s legal cases will go to a law firm affiliated with Ruiz, which will be hired as exclusive lead counsel to pursue those claims. And Ruiz and Sternberg are together involved in a couple of entirely separate business transactions, which might sow doubt about how objective Lionheart was able to be when evaluating MSP.

Besides purchasing a powerboat company together, Ruiz and Sternberg are on opposite sides of that Miami condo sale I mentioned.

MSP’s founder paid $15 million upfront for the $35 million property, according to the prospectus, with the balance (plus interest) covered by an assignment of MSP health-care claims. In the event that MSP completes a merger with Lionheart, Sternberg has the option of being paid in MSP shares. If the SPAC deal doesn’t close, Ruiz told me he’ll still buy the apartment using the claims as the part-payment currency, as originally anticipated.

A Lionheart spokesperson said that “rather than presenting a conflict, it is the exact opposite: [payment in MSP claims or shares] demonstrates that Mr. Sternberg … has confidence in the fundamental business model of MSP” — a sentiment Ruiz echoed.

At least Lionheart and MSP compromised in their price discussions: MSP initially valued the company at up to $50 billion but Lionheart told me it “wanted a lower valuation so as to provide its shareholders with a greater upside.” The SPAC also negotiated a highly unusual sweetener. Lionheart shareholders who agree to fund the merger instead of exercising their redemption right will split 1 billion warrants between them, exercisable at $11.50 a share. In theory, these warrants are valuable, and because the shares issued in exchange will be sold by MSP’s founders, conversion won’t result in dilution.

Yet shareholders still don’t seem convinced they’re being offered a good deal.

The prospectus is preliminary and the Securities and Exchange Commission hasn't yet provided feedback. It's normal for such documents to have multiple iterations before they are declared effective.

“Ultimately, the seller (the target) and the buyer (the SPAC) are both looking for the highest valuation possible,”a Cowen banker not involved in the MSP transaction wrote last year. “The SPAC is not terribly sensitive to what the valuation is as long as it clears the public market.”

Net revenue is the amount left after deducting the 50% of gross revenueowed to the claim assignor and 20% of gross revenue for Ruiz's law firm.

Net of the $70 milion transaction expenses

Oddy the slide deck published in July does include some valuation comps. Among those listed are private equity giants Blackstone Inc and KKR & Co Inc.

This applies if the balance has not already been covered by proceeds from the claims it owns. If shares are sold they'll come either come from Ruiz and his business partner, or by issuing new stock. Alternatively Ruiz and the business partner will pay any shortfall themselves.

The remainder is subject to a six months lock-up

Ruiz told the FT that “My number was much higher than $32.6bn. When we came back with the first models, they were at $50bn"

To put those numbers in context there will be roughly 3.3 billion shares outstanding post-merger and the exercise price is 15% higher than the per share transaction value. Exercising the new warrants won't deliver cash to the company; it will go to MSP's current owners.

Another indication of investor doubt is that Lionheart’s publicly traded warrants (separate from the 1 billion pot I mentioned) are selling for less than 90 cents. These may entitle the holders to receive a share of the company effectively for no additional outlay – the prospectus says the exercise price is expected to decrease to $0.0001 after giving effect to the issuance of the New Warrants and therefore “they are expected to be in the money as of closing”.The current price might reflect skepticism that the deal will close. It’s also possible market participants don’t fully understand the warrant structure. However, it might also indicate warrantholders don’t believe MSP is worth as much as its owners say.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Chris Bryant is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies. He previously worked for the Financial Times.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.