(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The time may finally be right for another big railroad deal. All it took was another economic downdraft.

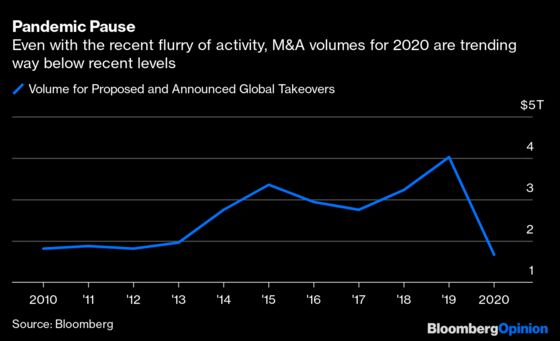

Private equity firms Blackstone Group Inc. and Global Infrastructure Partners are reportedly weighing a joint bid for Kansas City Southern that would value the railroad at about $21 billion including debt. Any takeover would also add to an aggressive flurry of dealmaking over the past few days after a pandemic-inspired lull. Siemens Healthineers AG agreed to buy U.S. radiotherapy company Varian Medical Systems Inc. for about $16 billion, while 7-Eleven owner Seven & i Holdings Co. is paying $21 billion for Marathon Petroleum Corp.’s Speedway gas stations. Waiting in the wings is a potential takeover of the popular video-sharing app TikTok and a Nvidia Corp. buyout of SoftBank Group Corp.’s Arm Ltd. chip-designing business. The sudden rash of dealmaking suggests buyers with supple balance sheets are getting more comfortable with the trajectory of an eventual recovery from the coronavirus pandemic, even as cases surge again.

It’s notable that railroads may be included in this latest deal frenzy. There hasn’t been a major takeover of a North American railroad since Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway Inc. struck a $36 billion deal for Burlington Northern Santa Fe in 2009. There were attempts by Canadian Pacific Railway Ltd. under the leadership of legendary railroader Hunter Harrison to seek a merger first with CSX Corp. in 2014 and then Norfolk Southern Corp. in 2015, but the carrier was rebuffed each time amid antitrust concerns. The failed talks showed the hurdles for any merger between the largest North American train operators after a wave of dealmaking in the late 1990s consolidated the industry into effectively seven main players, of which Kansas City Southern is the smallest and one of the few with major infrastructure in Mexico. As Buffett proved, though, a private investor is a different story.

The irony may be that Harrison, a big believer in the benefits of consolidation who died in 2017, may have done more to prolong the lull in railroad dealmaking than bring it back. Before his death, Harrison served a brief term as CEO of CSX. His tenure there was tumultuous and he managed to ruffle quite a few feathers, but in the end, he was able to prove to both investors and his fellow railroad CEOs that his signature “precision-scheduled railroading” — a strategy for reducing the capital, cars and people needed to run trains efficiently — could work for U.S. carriers.

Analysts had previous contended the U.S. railroads’ circuitous lines across mountainous terrain would make it more difficult for them to reach the levels of profitability that Harrison had produced at Canadian Pacific and at Canadian National Railway Co. before that. Posthumously, nearly all of his rivals — from Union Pacific Corp. to Norfolk Southern and, yes, Kansas City Southern— have adopted some form of precision-scheduled railroading. Burlington Northern is the only odd man out. The problem with this for would-be buyers of railroads is that this push for efficiency has increased both the profit margins and the stock prices of said railroads.

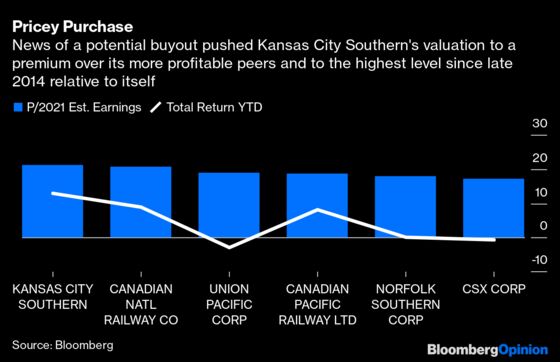

Before news of the potential private equity approach on Friday, Kansas City Southern was actually up about 2% for the year, compared with a nearly 12% slide for the S&P 500 Industrial Index and a virtually flat performance for the broader benchmark. The reported $21 billion price tag would value Kansas City Southern at a premium to its all-time high set in February and Bloomberg Intelligence analysts warn even that may not be high enough.

To justify a deal at these levels, the private equity buyers would have to be able to argue that the full scale of profit improvements under precision-scheduled railroading isn’t fully appreciated by the public markets. It’s hard to see how they do that. In January, before the worst of the pandemic, Kansas City Southern had predicted it would meet its 2021 goal of bringing its operating ratio — a measure of profitability where a lower number is better — down to the range of 60% to 61% a year early. The pandemic obviously undermined those plans. But even amid the sharp slump in volumes that’s ensued over the intervening months, Kansas City Southern in July raised its target for estimated cost savings this year to $95 million, excluding benefits from labor cuts and lease negotiations. That’s up from $61 million. After the rally on the deal news, the company trades at about 22 times estimated 2021 earnings, above the valuation commanded by other railroads that are further along in the process of precision-scheduled railroading.

This makes any transaction more of a bet on the future of trade between the U.S. and Mexico and a push to relocate manufacturing away from China. It’s a decent wager given the recent resurgence of interest among U.S. industrial companies to consider factories a bit closer to home. The caveat to that is Mexico’s more volatile regulatory and political environment. Amidst the pandemic, many manufacturers complained of a harsher approach to factory lockdowns across the border than in the U.S., a sign that the potential for supply-chain disruptions lingers even with the recently signed United States-Mexico-Canada trade agreement. I’m reminded of an interview with Harrison that I participated in at Bloomberg headquarters in 2015: “I don’t like Kansas City Southern because of the Mexico play,” he said. “I don’t like Mexico. I like to play in an arena where I know the rules, and I understand what might happen. That’s crazy down there.”

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brooke Sutherland is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering deals and industrial companies. She previously wrote an M&A column for Bloomberg News.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.