A 1.17% Return for a 98-Year Bond Issue? Sign Me Up

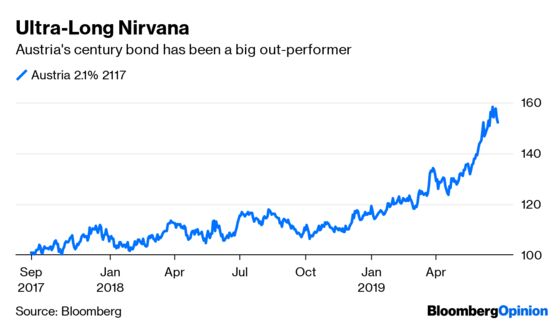

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- So even 1.2% wasn’t a low enough yield for Austria’s magic 100-year bond. The country managed to get a new sale away of this ultra-long duration paper with a staggeringly cheap 1.17% interest rate, and still the debt crowd was queuing up to buy it.

There were 5.3 billion euros ($6 billion) of orders for the 1.25 billion euro offer, which tells its own story. As I wrote on Tuesday, this must be the most vivid example yet of the markets’ desperate hunt for yield – any yield.

Rather than creating a new 100-year issue, Vienna decided to reopen its existing 2117 century bond to new takers. It did tap this same note three times last year to raise 1.1 billion euros, but that was when it was priced at between 108% and 116% of the bond’s original face value. The latest sale required new investors to pay 154% of the face value. It’s incredible that it was four times over-subscribed regardless.

The yield spread that was offered to investors above Austria’s benchmark 30-year bond (which yields about 0.7%) was also “walked in” (or reduced) by 7 basis points from the initial price discussions to get to that 1.17%, another sign of strong demand.

Now forgive me as I indulge in some real bond geekery, but it’s so-called “positive convexity” that these investors are really paying up for here – a big deal in the debt world. The market price of a bond rises when its yield falls and declines when its yield rises. But the attraction of ultra-long maturities with very low coupons is that their prices rise more sharply when yields fall than they decline when yields rise – hence the “positive” bit of that convexity phrase.

This all means the price outperforms when interest rates drop (as they’re doing now), which is overall good news for investors. It’s a little like owning a share in a company whose stock price is rising faster than its dividend yield is falling.

Still, it’s truly a first in global finance to raise funds of this size over a time period that’s beyond the expected mortality of any adult alive, but at yields that are beneath the euro area’s inflation rate. It shows how buy-and-hold investors such as pension funds and life insurers are having to secure high-quality assets that offer any form of yield. What it says about the future of Europe’s savings industry is another thing altogether.

The takeaway from this remarkable financing is that in 98 years’ time, Tuesday’s new investors can look forward to getting two-thirds of their money back after having enjoyed an annual return of barely 1% over the course of the rest of the 21st century and well into the next. Let’s hope the great-great-grandchildren are grateful.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Marcus Ashworth is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering European markets. He spent three decades in the banking industry, most recently as chief markets strategist at Haitong Securities in London.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.