16th-Century Traders Could've Predicted Zero Rates

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Critics of ultra-low interest rates keep waiting for a correction that might not come. Far from being an anomaly, near-zero borrowing costs may be the historical norm and a product of powerful forces at work for the past 800 years.

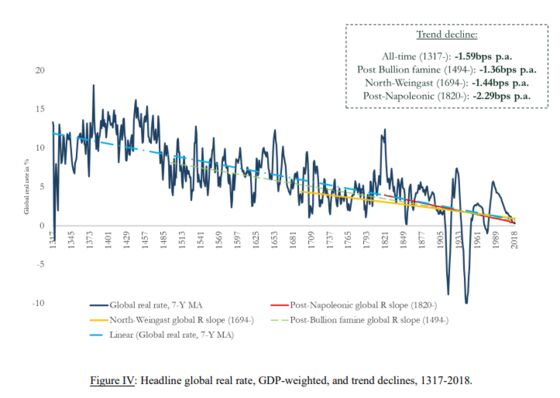

The price of money has been marching lower since the late Middle Ages, says Paul Schmelzing, a postdoctortal researcher at Yale School of Management and visiting researcher at the Bank of England, who traced this phenomenon in a paper last year. So pronounced is the long-term decline that neither wars nor monarchs — nor the arrival of central banks — have stood in the way, he reckons.

In that context, whether the Federal Reserve nudges its main rate up by a hair next year or the following seems like a small question. I corresponded with Schmelzing via email about negative rates, inflation targets and the next global benchmark for sovereign debt. (Schmelzing, who is working on a book based on his 2020 paper, said his views are personal and don't represent the U.K. central bank.)

Below is a lightly edited and condensed transcript of our exchange:

DANIEL MOSS: You've shown that interest rates have been grinding lower for centuries. Could we have predicted hundreds of years ago that rates would be as low as they are today?

PAUL SCHMELZING: An investor in the mid-16th century, or at the time of the French Revolution, could have extrapolated interest-rate trends in their own time, and would have concluded that roughly around the turn of the 21st century, the world economy would be grappling with the “zero lower bound.” On the eve of the Thirty Years War, global real rates had fallen by an average of 1.3 basis points per annum for 300 years, broadly in line with what continued over the following 400 years. Despite all the wars, sovereign defaults, or financial crises in history causing short-term reversals, the structural trend of falling rates has been remarkably consistent since the late Middle Ages.

DM: Markets are fixated on when interest rates will rise again to “normal levels.” Given the context of your research, is this the right question to be asking?

PS: Our definition of “normal” has been wrong for many years. Most observers who grew up in the 1960s and 1970s regard the rate levels during the oil shocks as an outlier in the upward direction, and rates since 2008 as an outlier in the reverse direction. They conclude that, eventually, these two shocks will cancel each other out, and things should go back to the 2%-4% real rate range with which they grew up. There will always be short- and medium-term volatility based on fiscal and monetary decisions, even years of apparent “regime changes.” But whether or not the Fed hikes, or another stimulus package is passed, long-run average rates have, in every case, eventually resumed their downward drift. Real rates actually show no tendency to “mean revert.”

DM: When some interest rates in Europe and Japan went negative a few years ago, there was a lot of commentary that suggested this was a freakish anomaly. Are there examples in history where this happened and life has moved on?

PS: We are, indeed, in uncharted territory on the nominal side. Long-term advanced-economy debt yielding negative nominal rates — as German bunds or Japanese government bonds have for a while — haven’t been seen since the time of Dante and the Crusades. However, what really matters are real (inflation-adjusted) yields. I am trying to show that on average around 20% of the time since the 14th century, advanced economies have seen negative real yields, with the 16th, 18th and 20th centuries being particularly notorious. Over the long run, investors have tolerated such poor returns because holding sovereign debt for them had other advantages.

DM: So what has been the driver of this relentless decline over time?

PS: Major switches in interest-rate regimes have until now been associated with a handful of “institutional revolutions,” like the founding of the Bank of England and the strengthening of Parliament in Britain in the 1690s. But that doesn’t really cut it. There is something more fundamental at play. People are generally becoming more risk-averse over the very long-term. We are also seeing the downward trend in other assets, such as private debt. So it's not a sovereign-specific story. Capital longevity increased every century. A typical bridge collapsed every few years during the Renaissance, houses burned down, wars destroyed major portions of the capital stock. Modern wars destroy less capital, while buildings can last centuries today. In turn, demand for real investments keeps falling.

DM: You note in the paper that financial centers have evolved over time. The U.S. 10-year wasn't always the global benchmark. You devote some space to Spain, for example. What happened to Spanish capital preeminence, and then to the Dutch?

PS: Changes of the reserve asset happen at glacial speed, historically. Transitions are preceded by years of growth, legal and innovative divergence between the old and new reserve center. Major geopolitical events then often mark the decisive catalyst for the final shift. Paul Kennedy popularized the term “imperial overstretch.” In practice, imperial overstretch went hand in hand with “financial overstretch.” The Spanish Empire by the late 16th century spent the equivalent of $1 trillion annually in the Dutch war theater alone, while growth rates hovered around zero. On some level, Cardinal Richelieu and the Dutch simply outsmarted the Spanish strategists during that crucial period. Of course, military spending can eventually turn out to be productive in many ways, boosting innovation and infrastructure projects such as the “Spanish Road” in this case. That argument is harder to make for modern state budgets, which mainly concentrate on welfare spending.

DM: We are often told that the most effective central banks are independent and with some kind of inflation target, usually around 2%. Does long-range history bear that view out?

PS: Current inflation volatility is at unusually low levels, even in the very long-run context. Only a handful of episodes really come close: the early 17th century, the mid-18th century and the Long Depression prior to World War I. Certainly, deflation was a much more frequent phenomenon in the early modern economy. Almost half of the years between the 14th and 18th centuries recorded price declines for the average urban household. Does this make modern central banks “effective?” Arguably, the risk of potential deflationary events may have historically disciplined debtors much more. There is evidence that fiscal and financial risks are today comparatively high, with debt levels at all-time highs. The two phenomena may be more closely connected than we appreciate.

DM: The past year has seen fresh projections that China's economy will surpass the U.S. in size. But the dollar is unchallenged as the global reserve currency and American interest rates are considered the global benchmark. Can this dichotomy between size and financial muscle remain indefinitely?

PS: Size isn’t the decisive factor. Venice was a city-republic of no more than 100,000 people, but the global reserve center for 200 years. Why? Venice patiently built a track record of not debasing its currency at will, keeping international promises, and ensuring that foreign creditors always had full legal recourse. French kings, ruling over the largest European economy and military in the early modern period, never managed to provide a “safe asset” because they kept throwing their creditors into jail, forcibly reducing interest rates at will, and permanently meddled with the value of their currency. As long as it resembles the France of Louis XIV much more than Italian city-states in terms of trustworthiness and institutional quality, China lacks very elementary requisites for gaining reserve status.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Daniel Moss is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian economies. Previously he was executive editor of Bloomberg News for global economics, and has led teams in Asia, Europe and North America.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.