The Most Important Number of the Week Is 85.6

For 2021, the MSCI All-Country World Index was up 16.9% through late Thursday, after surging 14.3% in 2020 and 24.1% in 2019.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Now comes the hard part. That’s the clear message from the world’s most sophisticated investors, controlling about 15% of all tradeable assets. You have to go back to the end of the 1990s to find a three-year stretch as good as the current one for the global stock market. For 2021, the MSCI All-Country World Index was up 16.9% through late Thursday, after surging 14.3% in 2020 and 24.1% in 2019.

These results may seem like a paradox given the raging global pandemic that has led to more than 5.4 million deaths globally, massive disruptions to supply chains that have made many goods scarce, evidence of accelerating climate change that has resulted in more severe natural disasters and soaring rates of inflation that have put the cost of such staples as food and shelter out of reach for many.

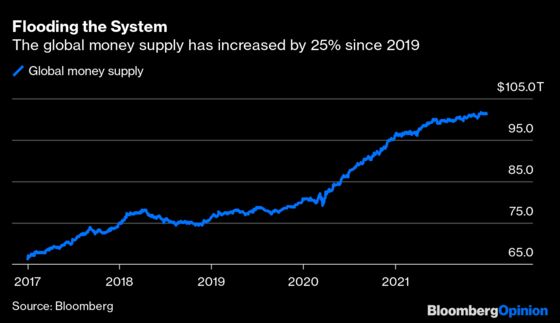

Nevertheless, it shouldn’t be hard to understand why financial assets have performed so well. Chalk it up to the rapid response by governments and central banks at the start of the pandemic to keep the initial economic shock from doing lasting damage. It would have seemed unimaginable in early 2021, but the Centre for Economics and Business Research now says the world economy is set to surpass $100 trillion for the first time in 2022, two years earlier than previously forecast. How did they do it? By throwing money at the problem. The combined fiscal and monetary stimulus efforts of the U.S., China, euro zone, Japan and eight other developed economies caused their aggregate money supply to increase by $20 trillion over the course of 2020 and 2021 to a record $100 trillion, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Let that sink in: The amount of money sloshing around the global economy and financial system surged by 25% over the course of two years. That’s unprecedented in modern times. There has to be consequences — and there are, namely in the form of bloated asset values and inflation, which just reached the highest in the U.S. since the early 1980s. So now the concern is that governments and central banks have done too much, and the only way to rebalance is to force economies into recession by abruptly shutting off the money spigot — and quick!

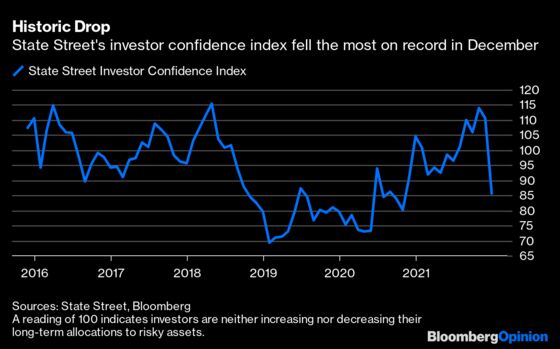

It should be obvious that such a scenario won’t be good for the stock market, which helps explain why State Street Global Markets said this week that its Investor Confidence Index suffered its biggest one-month drop on record in December. The gauge plunged 25.9 points to 85.6 from 111.5 in November. The reason why this measure is worth heeding is because it’s derived from actual trades rather than survey responses . It’s also important to know that the index is well below 100, the neutral level that indicates investors are neither increasing nor decreasing their long-term allocations to risky assets.

“Investor sentiment soured notably at the end of the year,” Marvin Loh, senior macro strategist at State Street Global Markets, said in a statement. “Positive investor sentiment will nonetheless be challenged by tightening financial conditions, high inflation and fiscal headwinds as we start 2022.”

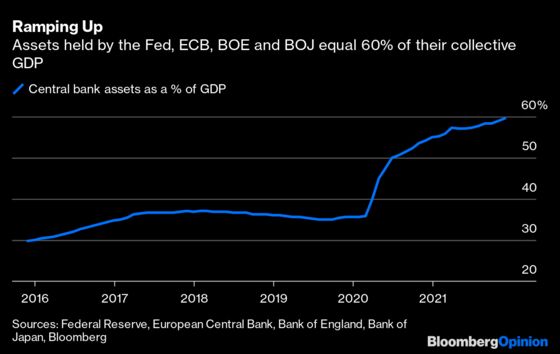

Of those challenges Loh highlights, perhaps the biggest is tighter financial conditions. Central banks have been very accommodating during the pandemic — perhaps too accommodating for too long. The collective balance sheet assets of the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, the Bank of Japan and the Bank of England shot up from about 36% of their countries’ total gross domestic product at the end of 2019 to 59.5% in November, Bloomberg data show. The Fed has started to taper the $120 billion a month it was pumping directly into the bond market, and plans to cut it to zero come March, sooner than the mid-2022 that it first forecast.

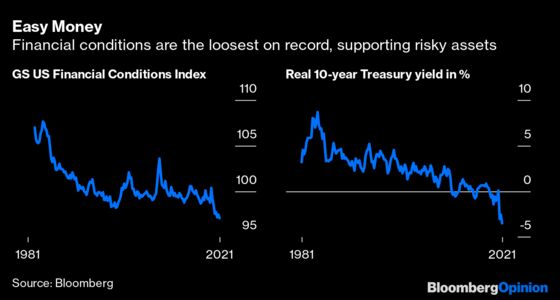

The net effect of all this central bank largesse has been the loosest financial conditions on record as tracked by a Goldman Sachs Group Inc. index. And a by-product of these loose conditions is that interest rates after adjusting for inflation are deeply negative, making cash and fixed-income assets unattractive relative to just about any other option. The Bloomberg Global Aggregate Index puts the average bond yield at just 1.33%, when inflation in the U.S alone is running at around 7% annually. That should continue to provide support for riskier assets.

To be sure, the global economy and financial markets are in unchartered territory. There is no playbook for how to unwind massive fiscal and monetary stimulus amid an ongoing pandemic and higher-than-average unemployment without inflicting damage. What is encouraging, though, is how the broad economy has managed to surprise to the upside these past two years. For example, members of the S&P 500 Index have exceeded earnings estimates by at least 10% on average for six quarters in a row, according to Bloomberg News.

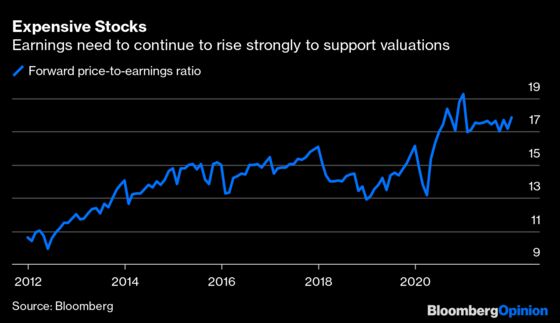

What worries those investors tracked by State Street is that the tailwinds that led to those pleasant surprises are about to quickly diminish. Simple discounted cash-flow analysis shows that higher interest rates make future earnings less valuable in the present, making it hard to justify the current high multiples for stocks without another year of above-average strong profit growth.

To be honest, one didn’t have to be a financial whiz to make money in these markets the last two years. Governments and central banks did all the heavy lifting for you. But it’s increasingly apparent that the rules of the game will change in 2022. The only questions are by how much and how bad the fallout will be.

More From Other Writers at Bloomberg Opinion:

- What Inflation in 2022 Will Say About Capitalism: John Authers

- Behold the Paranoid Style in American Investing: Chris Bryant

- Finding Cheaper Alternatives to Expensive Stocks: Nir Kaissar

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Robert Burgess is the executive editor for Bloomberg Opinion. He is the former global executive editor in charge of financial markets for Bloomberg News. As managing editor, he led the company’s news coverage of credit markets during the global financial crisis.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.