(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The last decade began with the narrow passage of the Affordable Care Act — President Barack Obama’s signature health-care legislation — over the strenuous objections of Republicans. It ended with most of the 2020 Democratic presidential field pushing for even more substantial change to a system the ACA only began to fix, and with Republicans once again in opposition. The debate continues.

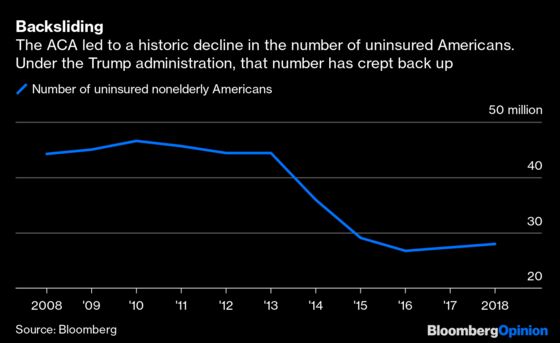

Under Obamacare, more than 20 million previously uninsured Americans now have health coverage, and many more have robust consumer protections. That has helped turn what was a controversial electoral weakness for Democrats in 2010 into a strength — so much so that failed Republican efforts to repeal the law helped Democrats take back the House majority in the most recent midterm elections.

Health care in the U.S. is still an expensive mess with big coverage gaps. If Democrats prevail in the 2020 election and can navigate some tricky policy and political barriers, America could get reform that begins needed fixes, or even paves the way for the universal coverage envisioned by some candidates’ Medicare for All plans. We don’t know as much about what Republicans would do. The party seems to have given up on coming up with a replacement for the ACA, even as it continues to pursue a lawsuit, backed by the Trump administration, that could eliminate it. It would almost certainly look like a less generous version of the status quo.

While Obamacare managed to achieve one of the most significant shifts to American health care in decades, the compromises required to push it through and Republican sabotage left it diminished. The law aimed to create a robust individual insurance market for people without employer coverage and boost Medicaid — and there has been progress on Medicaid expansion in holdout states. But the individual market never took off the way it was projected to, and even saw declines in recent years as premiums as out-of-pocket expenses often remained too high for many to want to join or stay in it.

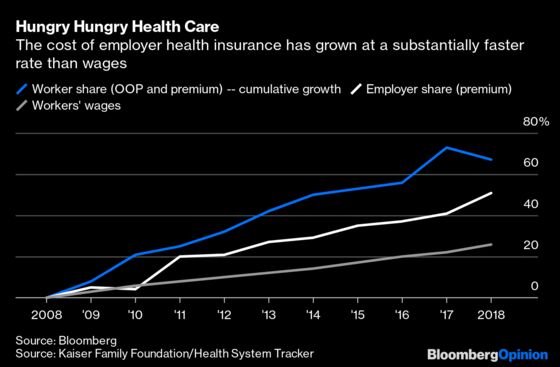

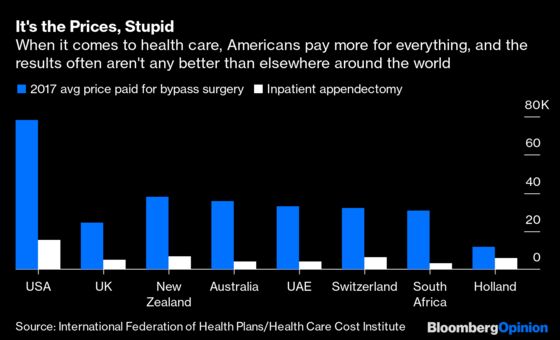

Even in a best-case scenario where Congress managed to fix its glitches, the ACA wouldn’t do enough to combat the biggest issue in U.S. health care: the fact that everything is entirely too expensive. To its credit, the law did a great deal to even out costs for consumers and expand coverage. That’s helped prevent bankruptcies and save lives. But the high prices that have resulted in rampant growth in health-care spending didn’t get as much attention. One crucial cost-control measure, a “Cadillac” tax on expensive employer plans, was scrapped in December after years of delay.

This big blind spot isn’t an accident. Health reform is difficult; there are entrenched provider, insurer, and drugmaker lobbies lined up against change. By focusing largely on measures that added customers instead of crimping profits and scrapping a planned public-insurance option, Democrats were able to get broad support that helped pass the ACA.

The GOP spent years impeding Obamacare’s implementation and arguing for repeal. When the party retook the White House and Congress in 2016, it attempted to follow through. That effort collapsed in the Senate after the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office projected that the party’s proposed replacement would skyrocket costs for sick people and see more than 20 million Americans lose health insurance.

Many in the Republican party now accept that something like the ACA’s protections for pre-existing conditions should exist, and probably hope that President Donald Trump’s lawsuit fails. That’s a significant move from the Tea Party “burn-everything-to-the-ground” days, though the GOP has a long way to go. Existing Republican policy sketches for a replacement fall well short of the ACA’s patient protections. Meanwhile, the Trump administration has slashed funding to market Obamacare plans and has boosted sales of shoddy short-term coverage. With administration encouragement, red states have pushed Medicaid work requirements. These policies don’t promote work, but do effectively use bureaucracy to cut health coverage for vulnerable low-income Americans.

On the positive side, some Republican lawmakers have joined modest bipartisan efforts aimed at surprise billing, abusive hospital contracting , and cutting drug spending by seniors. The Trump administration has independently proposed rules focused on drug cost and pricing transparency. Many of these ideas are well-intentioned and could conceivably reduce costs somewhat. If any manage to overcome internal dissension and make it past the effort stage, however, they’ll still fall well short of what Democrats have in mind.

Democrats’ next-generation plans are more willing to take on the health industry, which gives them a chance to do far more to rein in costs as they further expand coverage. Nearly every Democratic presidential candidate supports allowing the government to negotiate or curb drug prices. Several also propose threatening the patents of firms that don’t comply. These reforms would dramatically shrink spending on medicine.

Medicare for All — the most progressive of the proposals being debated, backed candidates Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren — would approach coverage and costs in a more effective but more disruptive fashion by moving everybody onto a single tax-financed plan and putting lower price controls in place.

But even on the moderate side of the primary field, proposed public options from candidates including Joe Biden, Pete Buttigieg and Michael Bloomberg go far beyond the one removed from the ACA. Some candidate plans allow people with employer insurance to jump to the public option and auto-enroll chunks of the population. That would add scale that should help push down costs. Multiple candidates also have proposed additional limits on what providers can charge, which would be a crucial restraint on the biggest source of health spending. (Bloomberg is founder and majority owner of Bloomberg Opinion parent company Bloomberg LP.)

All of these proposals tackle costs and it is among their biggest strengths, but it adds degrees of difficulty. Even if Democrats win back the White House and Senate, passage and implementation of even a moderate plan won’t be a cakewalk, as the bitter wrangling over the ACA forcefully demonstrates.

Reform takes longer than a single election cycle, and inevitably contains unpopular elements. If that once again leads to electoral difficulties, the GOP — not a fan of public options or a single-payer system — will once again become an impediment. If corporate lobbyists can’t derail reform altogether, they will work to delay, soften, or cut the more medicinal portions. There will be willing ears in Congress, as is evidenced by the repeal of the Cadillac tax and continued delay of surprise-billing legislation.

There’s a chance America will see reform that builds on or replaces the ACA over the next 10 years. The 2020 election will go a long way toward determining what more will still need to be done in 2029.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Max Nisen is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering biotech, pharma and health care. He previously wrote about management and corporate strategy for Quartz and Business Insider.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.