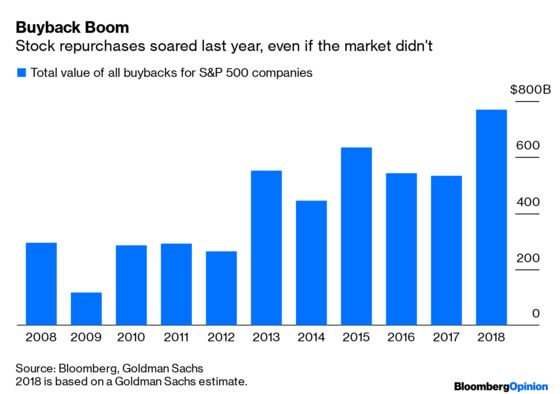

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Stock buybacks are a fraught and confusing issue. In recent years, the value of corporate share repurchases has soared:

A number of politicians have decried this practice, and sought restrictions or a ban. U.S. Senator Tammy Baldwin has led the charge against buybacks, while Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has labeled the practice a “pyramid scheme.”

Many observers are mystified by this animosity. Conventional wisdom says that share repurchases are like dividends -- a way to return money to shareholders. When companies don’t have any way to invest their money profitably, they might as well give the money back to investors. More companies are paying dividends now compared to a decade ago, so maybe buybacks are up for the same reason -- companies just can’t figure out how to invest their money productively. If so, that’s bad news for the economy, but it’s not a nefarious corporate scheme.

Complications arise, however, once the effect of repurchases on stock prices gets taken into account. Ocasio-Cortez’s claim that buybacks are a pyramid scheme relies on the notion that share repurchases artificially push up stock prices, thus providing a big reward to executives who are compensated with equity and options. That’s not really a pyramid scheme, but it could still represent a failure of corporate governance, if executives are being paid to take money out of their companies instead of investing it productively for the future. It would also mean that executives are using repurchases to manipulate prices -- the very reason that buybacks used to be illegal until 1982.

But it’s very hard to tell if buybacks actually have this effect. When companies repurchase their stock, it increases their earnings per share (by reducing the number of shares), so if investors value stocks based on a simple price-to-earnings multiple, the price will go up. But this would be a mistake on investors’ part, because removing cash from a company in a repurchase actually decreases the company’s value -- the investors who don’t sell their shares are now holding a larger piece of a smaller pie, so the share prices should remain unchanged.

Of course, that’s just theory; in reality, investors aren’t always rational, and corporate actions like buybacks can also send signals about what executives think about the company’s prospects. So ultimately it’s an empirical question. There is evidence that stock prices tend to rise after buybacks, but that doesn’t necessarily mean the latter causes the former. It could be that executives simply know when their companies are undervalued, and are timing the market on behalf of themselves and those shareholders who didn't sell. Or it could be, as some economists argue, that executives are using buybacks not to raises prices to irrationally high levels but to prevent them from going irrationally low after a run of bad news. Because the true value of stocks is very hard to know, it’s difficult to assess which of these stories is true. It’s also questionable whether stock-based compensation actually has anything to do with buybacks; executives who get paid in company stock don’t spend a higher share of their companies’ profits on repurchases than other executives, according to a Goldman Sachs report.

There are other concerns about buybacks besides price manipulation. Some worry that buybacks encourage companies to take on too much debt; economist J.W. Mason has noted that there is now very little correlation between corporate borrowing and capital investment. That suggests that companies are taking on debt to pay for buybacks, which could make them more vulnerable to bankruptcy. Yet other analysts argue that issuing new shares to employees tends to cancel out the shares retired in buybacks, and thus they see buybacks as a sneaky way to pay executives more.

In other words, no one really understands why repurchases happen or what they do. So should they be banned? On one hand, going back to the way things were before 1982 would still leave companies able to return cash to shareholders via dividends -- and if buybacks are just another form of dividends, then the effect wouldn’t be that large.

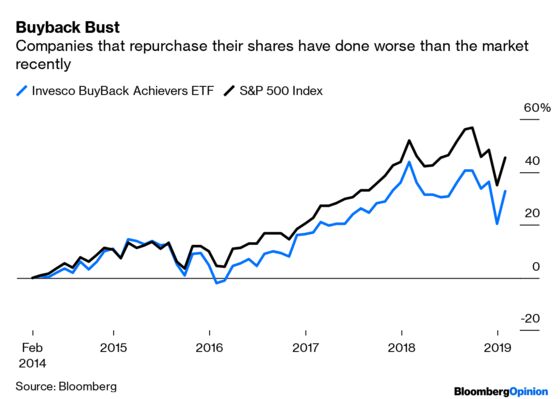

On the other hand, many of the concerns people have with buybacks probably could be better addressed by reforming other parts of the corporate system. If executive short-termism is the problem, stock- and option-based compensation should be discouraged. If debt is the problem, tax corporate borrowing more heavily. And it’s also possible that the issue could simply resolve itself -- in recent years, buybacks haven’t done much to help the stock prices of the companies that have tried them:

If repurchases really are supporting stock prices, legislators should be very careful about banning them. A market crash would wipe out a lot of personal wealth and could throw the country a recession. Perhaps instead of attacking buybacks, reformers should focus on fixing other parts of corporate America.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.