It's 2019, But It Sure Feels a Lot Like 1998 for Stocks

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- If you like historical parallels, as I do, and particularly about markets, then here’s an intriguing one: What’s happening now in 2019 looks and feels a lot like it did in 1998. The obvious similarities are that, now as then, a U.S. president faces the threat of impeachment against the backdrop of a strong economy and surging stock market. Even “Friends” is still popular today, just as it was then. But it’s the finer affinities within those broader parallels that are most interesting, and in some ways instructive. Let’s take a look.

For starters, when the U.S. House of Representatives commenced impeachment proceedings against Bill Clinton in October 1998, the then U.S. economic expansion was nearing the longest on record and would become the longest just over a year later. Donald Trump’s impeachment inquiry also coincides with an unusually long expansion, which overtook the Clinton-era boom last summer.

Another similarity is that the Federal Reserve cut short-term interest rates three times this year, as it did in 1998, to ward off concerns that the economy is slowing. Both times, the necessity of those cuts was far from evident, as the Fed’s dual mandate of maximum employment and price stability appeared to be safely in hand. The unemployment rate averaged 3.7% during the first 10 months of this year, compared with 4.5% over the same time in 1998. And core PCE, the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge, has averaged 1.6% so far this year, compared with 1.3% in 1998.

Then there’s the equity market. The freakishly resilient economy has been overshadowed by a stock market propelled to all-time highs by investors’ renewed obsession with technology. In 1998, every conceivable business — from pet products to groceries and toy stores — put up a website and called itself a tech company. Sound familiar? Everything is technology again, including retailers, office buildings, media companies, car makers and, yes, even the drivers.

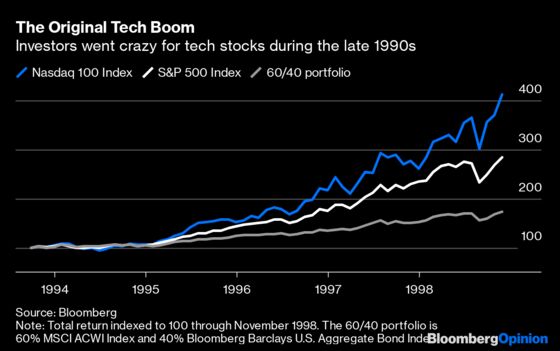

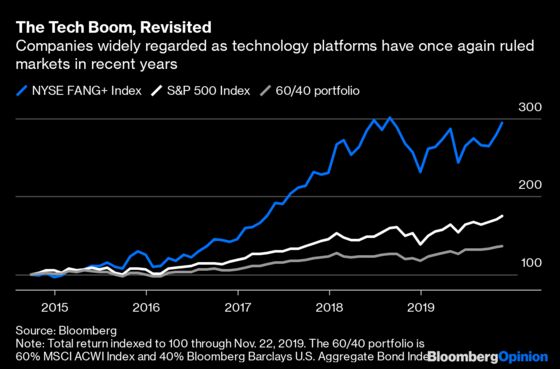

Tech enthusiasts are back on the chase. The NYSE FANG+ Index is to techies today what the Nasdaq 100 Index was in the late 1990s, housing investor darlings such as Tesla Inc., Netflix Inc., Amazon.com Inc., Facebook Inc. and Google parent Alphabet Inc. It has returned a blistering 23.2% a year from October 2014 through Friday, including dividends, the longest period for which numbers are available. That’s 11.8 percentage points a year better than the S&P 500 Index over the same period, nearly the same margin by which the Nasdaq 100 outpaced the S&P 500 over the same time through November 1998.

And once again, it’s been a miserable period for investors who declined to ditch their portfolios and chase tech. The FANG index has outpaced a balanced 60/40 portfolio of global stocks and U.S. bonds — as represented by the MSCI All Country World Index and Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index — by a crushing 17 percentage points a year since October 2014, a reflection of low interest rates and sluggish foreign stock markets. Here, too, that’s nearly the same margin by which the Nasdaq 100 outpaced the 60/40 portfolio over the same time through November 1998.

Those similarities are coincidental, of course, but it’s worth bearing in mind what followed back in November 1998. Over the next 16 months, rather than reverse course, the economy, the stock market and technology stocks all raced ahead, never mind the political circus swirling around them. The Nasdaq 100 gained another 183% from December 1998 to March 2000, while the S&P 500 and the 60/40 portfolio settled for 31% and 20%, respectively.

The fear of missing out unleashed on investors already raw with tech envy during those fateful 16 months was more than many could bear. Perhaps most famous among them is billionaire investor Stanley Druckenmiller, who scooped up internet stocks in 1999 after betting against them earlier that year. Drunk with success, he plowed an additional $6 billion into tech stocks just before they collapsed in early 2000, handing him a $3 billion loss. Druckenmiller later recalled, “I already knew that I wasn’t supposed to do that. I was just an emotional basket case and couldn’t help myself.” He may as well have been speaking for an entire generation of investors.

That doesn’t mean the end of the FANG era is imminent. On the contrary, 1998 is a good reminder that the agony of investors who managed to sidestep the fad so far may become the catalyst that keeps the party going a while longer.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nir Kaissar is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the markets. He is the founder of Unison Advisors, an asset management firm. He has worked as a lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell and a consultant at Ernst & Young.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.