(Bloomberg Opinion) -- If one day you’re banned from buying your dream second home (or third, or tenth, or whatever) in the country of your choice, you’ll know whom to blame: tech tycoon Peter Thiel.

Fears about a property bubble in New Zealand reached a denouement last week with a law banning nonresident foreigners from buying a home. The trend for billionaires like Thiel to discreetly snap up prime real estate in the country — some in preparation for the coming apocalypse — certainly didn’t enamor local people and politicians to overseas buyers.

The ban, which won’t affect Thiel because he’s gained New Zealand citizenship, is admittedly a crude measure and one that might make a geographically isolated country appear somewhat xenophobic. Barriers to foreign ownership aren’t a panacea for rocketing house prices. If they were, Switzerland would be cheaper.

There may be a negative impact too on the building of new housing in New Zealand and foreign direct investment there, as the International Monetary Fund warns.

Still, as a millennial priced out of several property markets, it’s hard for me not to feel some sympathy with the Kiwis here. It’s a clumsy approach, to be sure, but at least they’re trying something. The global housing bubble has been inflated in part by speculative international capital. New Zealand’s angry rejection of the itinerant, propertied classes probably won’t be the last.

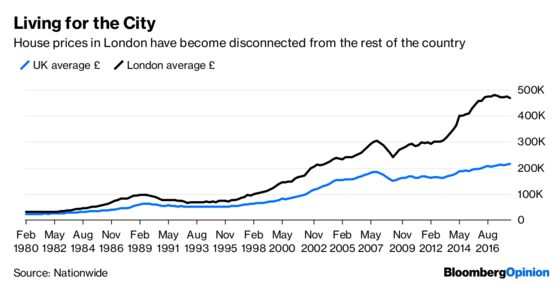

The root cause of the resentment is well-explored. A house has ceased being a mere necessity — a roof over our heads — and has morphed into an asset class. Prices have soared in desirable cities around the world. Local people weren’t consulted; it just happened. Existing homeowners, primarily older people, have benefited while everyone else is forced to spend much more of their pay on rent.

In fairness, foreign buyers are only part of the problem. In New Zealand, they make up a sliver of purchases — although the proportion’s much higher in exclusive locations like central London. They can become scapegoats for things politicians can’t or won’t control. House prices have risen primarily because of rock-bottom interest rates, driven by central-bank policy.

London’s sky-high prices reflect much more than its emergence as a playground for plutocrats. They’re also a function of population growth and barriers to more home building.

But pretending that foreign capital doesn’t affect local property markets is naïve. Overseas buyers are often concentrated in prime areas, but there’s a trickle-down effect. Wealthy domestic buyers are displaced from those locations and bid up prices for smaller homes or those in less desirable areas. According to a study from the Royal Economic Society, average house prices in England and Wales in 2014 would have been about 19 percent lower in the absence of foreign investment.

Globe-trotting buyers are probably less price-conscious, too. A foreigner purchasing a home in Berlin, say, might reflect on how cheap it is compared to similar in London or New York. Hence, they’ll pay a price a local person would consider obscene.

In theory, this extra demand should provoke a supply response, causing prices to fall again. But in practice that often isn’t the case because of tight planning or building regulations. Or the wrong type of accommodation is built to attract overseas capital. In London, there’s a surplus of luxury riverside flats, but at 1 million pounds and upward most are unaffordable for locals.

There are measures to curb speculation that are less drastic than New Zealand’s, such as higher stamp duty or capital gains tax on homes purchased by foreigners. Prices in London are moderating slightly after various tax changes, although Brexit has played a big part, too.

Looked at globally, however, trying to deter foreign money can be a bit like playing Whac-a-mole. As soon as you legislate in one city, buyers pop up elsewhere, as Canadians will attest. That’s because these interventions target the effect, not the cause of property speculation.

And that cause? Foreign money looking for a home. Only Beijing has the power to discourage wealthy Chinese from snapping up overseas property, for example, something that’s helped feed bubbles from Sydney to Toronto.

In the absence of being able to control this demand, we should at least make the market more transparent. Forcing foreign buyers to disclose the ultimate owners of their property, as the U.K government has belatedly proposed, is a necessary step. It’s far too easy for people to launder money through real estate, often via anonymous shell companies.

In one way at least, New Zealand is right. Instead of indulging the doomsday fantasies of billionaires, we should be pulling on every lever to deal with the very real affordability crisis in housing.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Chris Bryant is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies. He previously worked for the Financial Times.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.