Bond Market Suggests Fed Isn’t the World’s Central Bank

Bond traders see Fed as the world’s most influential central bank, not the world’s central bank. And that makes a difference.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- For U.S. bond investors, the summer hiatus from Federal Reserve speakers couldn’t have come at a better time.

Since the central bank left interest rates unchanged on Aug. 1, only two officials have made public comments: Richmond Fed President Tom Barkin on Aug. 8 and Chicago Fed President Charles Evans on Aug. 9. None are scheduled to talk again until Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic on Aug. 20. Of course, traders around the global have fixated almost exclusively on Turkey since Aug. 10, when President Recep Tayyip Erdogan declared his refusal to bow to U.S. political demands and market pressures. The ensuing meltdown has rippled across emerging markets, from South Africa to Argentina.

It’s times like these that might have caused past Fed leaders to point to “global risks” and the need to be patient with future interest-rate increases. After all, part of the reason for concern about emerging-market countries is that non-U.S. borrowers have added trillions in dollar-denominated debt in the post-crisis years. With rate increases come higher borrowing costs and usually a stronger U.S. dollar, making it harder to repay creditors.

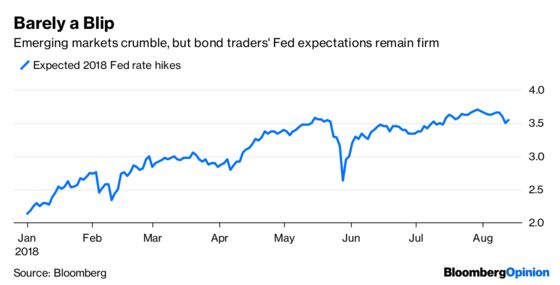

You’d never know of the consternation from glancing at the $15 trillion U.S. Treasury market. The benchmark 10-year yield is hovering just above its 2018 average after trading little changed on Monday. The futures market is still pricing in closer to two additional Fed rate hikes by the end of the year, just about the same as a week ago. Interest-rate volatility is up but remains 18 percent lower than at the end of May, when Italian yields soared in a fleeting bout of panic.

Why the subdued reaction from the supposed safe haven? For one, the consensus seems to be that there’s not going to be much spillover into developed markets. The biggest threat comes from the European banks that had large exposure to Turkish assets, but even that seems mostly contained.

The lack of Fedspeak doesn’t hurt, either. With no new information on the central bank’s thinking, traders are left to take at face value officials’ recent median projection of two more hikes in 2018. And with that, U.S. yields seem to have a floor.

Even if Fed Chairman Jerome Powell were speaking, though, it’s doubtful he’d fret much about the market fluctuations. The central bank has largely looked past the hiccups since the end of 2016. Plus, the U.S. unemployment rate is below 4 percent and the Fed’s preferred inflation metric has been at or above 2 percent for four consecutive months, the longest stretch since 2012. There’s really very little to doubt their resolve, aside from souring market sentiment.

What makes Treasuries’ resilience all the more impressive is that speculators have huge one-way bets on yields moving higher. They’ve never held a larger net short position in five-year note futures, and their wagers on losses in 10-year futures are also near a record. Chaos in emerging-market assets is usually a time to cut back on those positions for fear of even steeper losses in a haven rally. But so far, there’s little evidence of a shakeout.

That speaks to the fact that bond traders see the Fed as arguably the world’s most influential central bank, but not the world’s central bank. And that distinction makes a big difference.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.