'Popularism' on Climate Won't Help Biden or the Planet

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- We all buy insurance, but as a product it’s still a tough sell. Paying for the intangible risk of the unthinkable happening might be necessary. But popular? That would be a stretch.

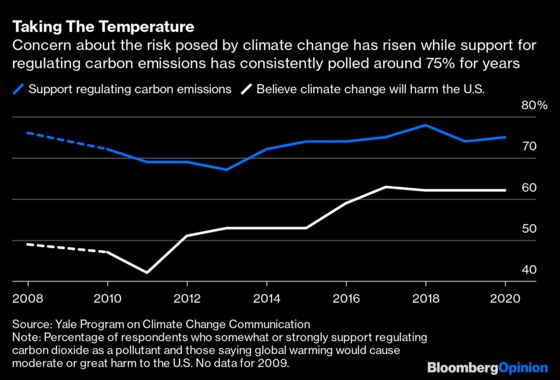

Climate policy is similar. Americans’ concern about climate change has risen over time, and most favor measures to address it.

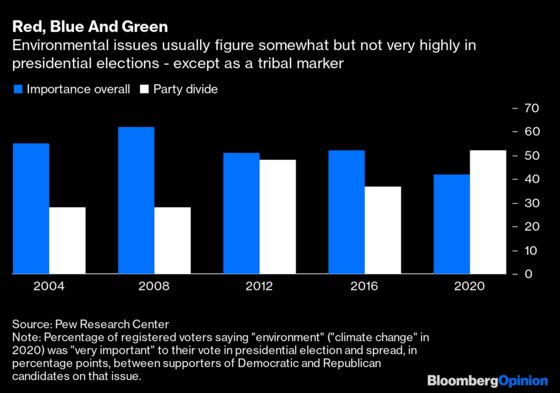

Yet it’s never quite a priority come election day. In the past five presidential contests, “climate change” or “environment” usually ranked reasonably high in terms of importance, based on Pew Research Center polling, but always well below other issues such as the economy. It actually dropped lower in 2020.

However, the issue has offered a reliable and growing wedge issue for Democrats and Republicans. It divided voters more than any other major issue in all of those elections barring 2008, when it was still the second-most divisive. This includes 2020. Think about that: The divide on climate change last summer was actually wider than over Covid-19 or racial inequality.

This is the context for climate’s place in the debate about “popularism,” pollster David Shor’s thesis for Democratic campaigning that was dissected in a recent New York Times op-ed by Ezra Klein. A tactical approach rooted in former President Barack Obama’s victories, popularism essentially involves incessant polling to rank the popularity of the party’s views and then talking a lot about the popular ones while staying quiet on less-popular ones.

Straight away, this presents a problem with comprehensive climate policy, which entails refashioning swathes of U.S. industry. So a plan to sotto voce that stuff and then slip it onto the president’s desk after you’ve won just seems a bit unrealistic. By definition, addressing climate change means upfront costs to head off a seemingly abstract threat. It’s insurance; not unpopular, necessarily, but hardly electoral dynamite either.

That’s why it piggybacks on other things. During Obama’s first term, the push for emissions cap-and-trade legislation benefited from then-recent record oil prices and national security concerns about dependence on imports. It failed anyway. Similarly, while President Joe Biden hasn’t downplayed his climate agenda, he has certainly up-played its other aspects: economic recovery, infrastructure, even rivalry with China. Yet, despite also not letting a good crisis go to waste, his program faces Republican stonewalling and Democratic division.

Kevin Book of ClearView Energy Partners, a Washington-based analysis firm, suggests that, in both cases, time ran, or is running, out: “It’s that “thud” you hear when a slow-moving government tries to piggyback onto a fast-moving crisis.” Oil’s collapse in late 2008 was linked to the financial crisis, which eclipsed environmental concerns. The nascent shale boom then neutered the national security argument and provided jobs Obama needed. Today, the economic recovery from Covid-19, while fitful, has at times blunted the jobs argument while stoking critiques centered on inflation or public debt.

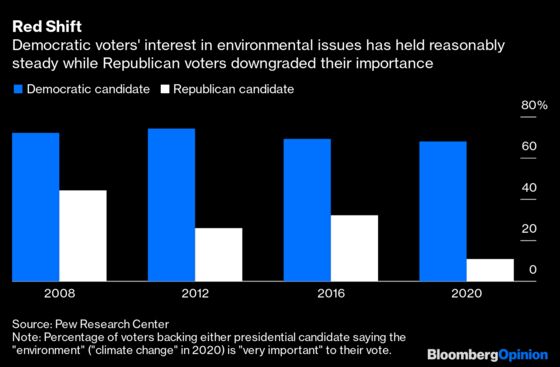

The attempt to leverage crises in part reflects the need to overcome that divide in the Pew polling. While the environment’s importance has decreased somewhat for Democratic voters, virtually all of the widening reflects Republicans downgrading the issue.

There are structural factors that may align Republicans this way. Red-leaning states tend to host more fossil-fuel production and generate higher emissions per head (which could be taxed). But there is more to it than that. It hardly seems a coincidence that Republican ambivalence deepened as, motivated by the near-miss of cap-and-trade, fossil-fuel lobbyists worked to harness Tea Party activism toward their interests. Nor that it reached its nadir in the 2020 election, featuring an incumbent who decried climate change as a hoax, backed by a party that has embraced conspiracy theories on everything from vaccines to the result of that same election.

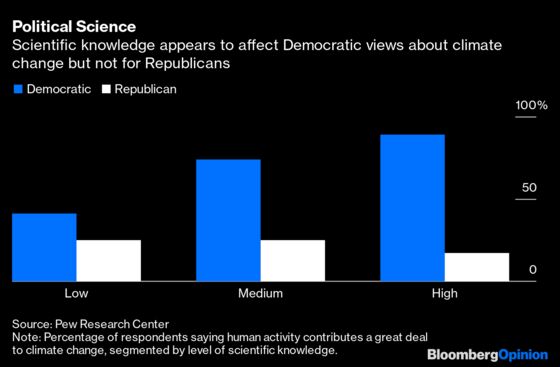

There are two other relevant aspects of Shor’s thesis here. One is that educational attainment is now a primary force for polarization, as Democrats do better with college-educated people while Republicans have won more of the larger, non-college population, especially under former President Donald Trump. The second is that, to avoid electoral oblivion, Democrats must win back some of the white working-class voters who flipped from Obama to Trump, including the non-college cohort who went heavily for the latter.

Educational polarization seems less relevant for climate policy, however. In polling conducted in late 2019, Pew assessed respondents’ level of scientific knowledge and how that matched with both their party affiliation and their view on human activity causing climate change. This showed scientific knowledge affected views among Democrats but hardly at all for Republicans. The Yale Program on Climate Change Communication reports similar findings.

All this adds to the sense that climate policy has become just another front in the culture war. On that basis, it’s even harder to see the relevance of popularism here. An issue of middling importance come election day anyway, talking climate down seems more likely to demoralize parts of the Democratic base than win many Republicans over. You can pretty much guarantee Fox News would run endless coverage of it anyway, which counts for far more. There’s a decent chance the 2024 election will feature a GOP presidential candidate still insisting he didn’t lose the last one, rendering any DNC missive along the lines of “ixnay on imateclay” a tad irrelevant.

As it stands, Biden’s repackaging of climate policy as job-creation looks like a fair stab at popularism and also about as far as he can take it within his own party. The progressive activism that elevated climate on the Democratic platform may well irk important internal gatekeepers such as Senator Joe Manchin. On the other hand, without such activism, how would the issue of climate advance with any sort of momentum at the federal level at all? Manchin reportedly may squash key parts of Biden’s climate policy. But given his obvious incentives to defend the coal business, it’s again unclear exactly how changing the messaging would persuade him to support measures at a level concomitant with the threat.

Beyond the current focus on jobs and economic renewal, it’s hard to imagine what could shift the embedded dynamics around climate policy in short order. Some other way of repackaging it may yet emerge, perhaps. One example, as argued by politics professor and author Anatol Lieven, is to harness nationalism, framing climate measures as a patriotic act rather than a multilateral effort. However, calling on people to do right by their country doesn’t seem that different a message from the familiar, and seemingly feeble, one of doing it for the kids. Plus, we just suffered an acute crisis that didn’t do much to unite us, last time I looked.

Possibly the best thing climate policy has going for it is (what else?) money. Capital markets are there already on energy transition, and the technologies to address the issue have gotten dramatically cheaper over time. As costs fall, and sectors such as auto manufacturing shift budgets decisively away from fossil fuels, so it gets harder to hold a position at odds with these trends.

The growing friction between the Republican Party and its traditional corporate allies over other wedge issues such as vaccine mandates is worth mentioning here too. As it is, the congressional GOP’s broad climate denial of yesteryear has cracked a bit, with some members now acknowledging the threat, albeit proposing limited measures against it. On that front, it’s notable that North Carolina just enacted a net-zero mandate for its power sector, the first Republican-led state legislature to do so.

Passing any sort of support for transition via reconciliation would help to speed this process along, which is vital given the urgent need for action and the likelihood Democrats will lose control of at least one chamber in the midterms. Investment leading to real benefits in the form of new infrastructure, reduced local pollution (more tangible than carbon dioxide) and good jobs offers the surest, if not necessarily quickest, route to persuading more Americans to prioritize climate change.

And at some point, the sheer weight of money behind transition might even push some future Republican leader to provide permission for their voters to back it too. Popularity, like any other commodity, can be bought.

Former President Barack Obama’s signature issue, healthcare, pipped the environmentby just one percentage point.

See, for example, chapter 20 of Christopher Leonard's "Kochland" (Simon & Schuster, 2019).

"Climate Change and the Nation State: The Case for Nationalism," Anatol Lieven (Oxford University Press, 2020).

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.