'Peak TV' Might Also Mean Peak Employment in Hollywood

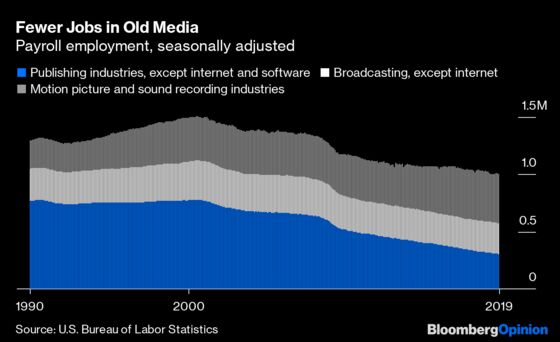

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Working in the media can be lots of fun, but it hasn’t been the greatest place to build a career over the past two decades. Employment at print publishers has plummeted with the rise of the internet, and broadcasters have downsized too. The jobs created in new media, which in Bureau of Labor Statistics’ employment data fall mostly in the ungainly category of internet publishing and broadcasting and web search portals, come nowhere close to making up for the losses elsewhere since 2000.

Still, there is one old media sector that has been holding up just fine: There are 11% more jobs in motion picture and sound recording industries in 2019 than there were in 2000.

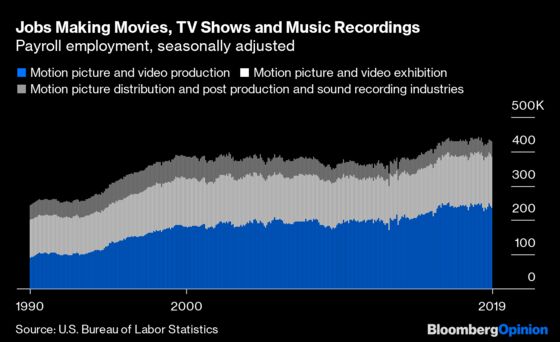

It sure isn’t the music business that’s driving these gains: according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, employment in the industry is down almost 40% since 2001. There has been an increase in employment in motion picture and video exhibition, which may in part be due to the rise of more labor-intensive movie theaters that serve alcoholic beverages and nice food. But most of job gains have come in motion picture and video production. In other words, Hollywood!

The numbers above understate the total employment effect, as more jobs in motion picture and video production also mean more jobs for accountants, carpenters, caterers and all sorts of other people. And while we call it “Hollywood,” lots of the jobs are actually in New York, Atlanta and other locales.

But it’s the trajectory that interests me here. Why has film and TV production held up so much better than other legacy media industries? And what’s up with that rise in the 1990s, the long flat stretch after 2000, and the rise from 2013 through 2017?

In answer to the first question, Hollywood catered to a national, even global audience almost from the beginning, and thus hasn’t suffered from the collapse of local media business models in the way that newspapers and parts of broadcasting have. Relatedly, it also wasn’t so advertising-dependent, and thus has been less vulnerable to Facebook and Google’s conquest of the advertising industry. And while competition from user-generated media and video games has taken screen time away from Hollywood’s products and will continue to do so, there’s clearly still a lot of demand for high-quality narrative video.

As for why Hollywood employment has risen over some periods but not others, I took a stab at annotating the chart.

OK, the 1990s employment gains probably weren’t all or even mostly about HBO’s “The Larry Sanders Show.” That acclaimed comedy was an early (although far from the earliest) landmark in the rise of original series paid for by cable channels, which provided a lucrative new outlet for makers of TV series who previously had only the three big broadcast networks to sell to. Others included cartoons such as Nickelodeon’s “Ren and Stimpy” (which premiered in 1991) and MTV’s “Beavis and Butt-Head” (1993), and early reality series such as MTV’s “The Real World” (1992) and “Road Rules” (1994). Later in the decade came HBO’s high-end scripted series “Sex and the City” (1998) and “The Sopranos” (1999).

Boom times for U.S. movie makers may have had as much or more impact on the 1990s jobs numbers than TV did. Domestic ticket sales rose after a flat 1980s, foreign markets grew in importance and the rise of the DVD created a big new revenue stream. From 1990 to 1998, according to consulting firm Monitor Deloitte, the number of U.S.-developed theatrical films rose 67%, from 319 to 534, while the number of U.S.-developed TV productions of all sorts rose 36%, from 397 to 541.

Those higher production volumes brought pressure to cut costs. One reaction was to do more filming abroad. Another was to increase reliance on reality shows, which usually require a lot fewer people (especially unionized people such as actors and writers) than scripted programs. Competition-based reality TV first took off in Europe in the 1990s, and after CBS brought “Big Brother” (originally from the Netherlands) and “Survivor” (from the U.K. and Sweden) to the U.S. in 2000, the format for a time seemed destined to completely take over broadcast TV here. Hollywood was able to keep employment steady through this reality-TV onslaught thanks to overseas movie markets plus continued growth in the number of scripted shows on cable, but the trend did not seem to be the industry’s friend.

Then Netflix came to the rescue with “House of Cards,” the first of a flood of original programming that it and rival streaming providers commissioned to lure and keep customers. The number of scripted series for television nearly doubled from 2011 to 2018, according to FX Networks, with streaming services accounting for the vast majority of the gains.

Can it continue? The 495 scripted series that aired in 2018 amounted to only a modest rise over 2017’s 487, a slowdown that seems to be reflected in the jobs numbers. The past few years might turn out to have been “peak TV,” and peak employment in motion picture and video production might turn out to have come and gone.

Or it might not. This has proved to be quite the resilient industry, after all. The Bureau of Labor Statistics is still projecting a 5.5% increase in motion picture and video industry employment through 2018. The narrow occupational categories expected to see the biggest employment gains are:

- film and video editors, 3,800 new jobs

- producers and directors, 3,000 new jobs

Part of what’s going on is that social media networks, YouTube and other nontraditional content channels — and advertisers —are hungry for programming that doesn’t require Hollywood-level production budgets but does still need people to create, direct, edit and produce it. These generally aren’t Martin-Scorsese-type jobs. Still, if you’ve always wanted to direct, it’s nice to know that you needn’t give up hope just yet.

The number of waiters and waitresses working in motion picture and video industries has risen from 510 in 2010 to 3,510in 2018, and the number of bartenders from 150 to 1,910.

That is, including distribution, exhibition and post-production as well as production.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Sarah Green Carmichael at sgreencarmic@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.