Why in India, 6% Economic Growth Is Cause for Alarm

The slowest expansion in six years has put India behind China, Indonesia and a few others in the region.

(Bloomberg) -- For almost half a decade Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi headed the fastest-growing major economy in the world. Now, what looks set to be the slowest expansion in over a decade is putting India behind China, Indonesia and a few others in the region. Waning consumption at home, troubled banks and a gloomy global outlook are being blamed, prompting a flurry of government measures. Surging food prices are adding to the malaise. At risk are efforts to reduce poverty in Asia’s third-largest economy and the ability to generate jobs for the more than 10 million young people entering the workforce each year.

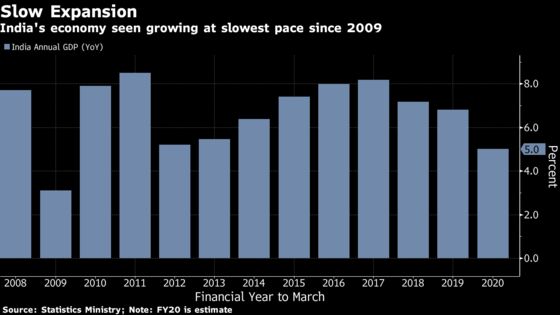

1. How deep is the slowdown?

The Statistics office estimates growth slowed to 5% this fiscal year, which ends March 31. That is a far cry from the 8.2% expansion seen in 2017 and the slowest since 2009, when the global financial crisis hit. The government sees manufacturing output growing at just 2%, compared with 6.9% last year, while expansion of the dominant services sector is down to 6.4% from 7.7%. The slowdown across sectors highlights a slump in consumption, which makes up about 60% of GDP. That can be attributed in part to a crisis among shadow lenders and a build-up of bad loans at banks, which in turn curbed lending in the economy. Waning consumer confidence and unemployment at a more than four-decade high have also hurt.

2. Is 5% not good enough?

Not really. If Modi wants to make his pledge to turn the country into a $5 trillion economy by 2024, from $2.7 trillion now, India needs its economy to expand at a 9%-10% pace for a sustained period of time. With growth slowing for the past six straight quarters, and little sign of a sharp rebound, that’s a setback for efforts to fix the extreme income gap. In a country of 1.3 billion people, India’s per capita income is about $2,000 a year -- dwarfed by China’s $9,800 and the U.S.’s $62,600. So while 5%-plus expansion might look good on paper, India needs faster growth just to catch up with other Asian countries such as Indonesia, where per capita income is at $3,900, and South Korea’s $31,000.

3. But isn’t growth slowing in the rest of the world?

Yes, the U.S.-China trade war is rippling across the globe, putting a brake on world growth. That and various internal factors have been weighing on China’s growth, which some economists expect to slow to just under 6% this year. The trade fallout is hurting India’s exports as well, but the bigger problem is the slide in domestic consumption. International Monetary Fund Chief Economist Gita Gopinath said in December that poor business sentiment and declining rural consumption were among the reasons for weakness in India’s economy, adding that its growth forecast was likely to be cut.

4. Why is consumer spending so weak?

The economy has been shedding jobs, for one thing. The unemployment rate jumped to a 45-year high of 6.1% in 2018 and anecdotal evidence suggests that there’s more pain to come as the struggling auto sector -- which makes up almost half of India’s manufacturing -- continues to cut jobs. With overall manufacturing, which contributes about a fifth to the economy, barely growing, businesses are curbing investment. Farm income also has been subdued. Making matters much worse, prices of almost everything are soaring. Headline inflation surged to a more than five-year high in December, breaching the central bank’s 6% tolerance limit -- making it harder for policy makers to stimulate the economy. Most worryingly, food price inflation accelerated 14.1%, led by a jump in vegetable costs.

5. What do India’s banks have to do with the slowdown?

Banks have been cautious about lending in the past few years as they grapple with non-performing loans. Their withdrawal saw so-called shadow banks emerge. In the past year or so, these non-bank lenders have faced their own troubles following a default by one of the biggest institutions, IL&FS Ltd., which set off a liquidity crisis. Shadow lenders fund everyone from small-time entrepreneurs seeking startup funds to property tycoons looking to roll over debt, and when they curbed loans, consumer spending started to tail off.

6. What do experts say?

Reserve Bank of India Governor Shaktikanta Das says the slowdown is cyclical, which means business activity will pick up when the cycle turns. He cut interest rates five times last year to help cushion the economy and pumped liquidity into markets, but says the government also needs to fix structural weaknesses, like making it more easier to do business in India. Many economists say the outlook is subdued.

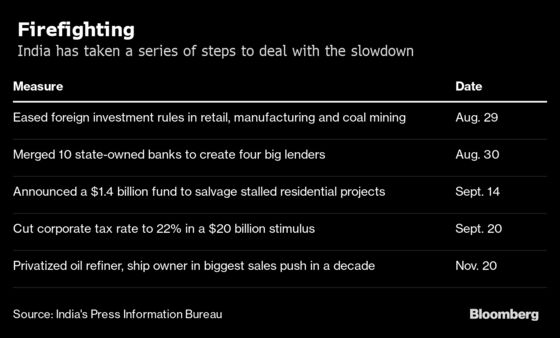

7. What’s the government doing?

Most of the measures have focused on encouraging investment rather than domestic demand. It announced $20 billion in tax cuts to companies. It plans to merge weak state-run banks with stronger ones, hoping that can spur lending. Foreign investment rules were eased and a special real-estate fund was set up to salvage stalled residential projects. It also will sell state assets in India’s biggest privatization drive in more than a decade. In December, the government outlined a $1.5 trillion plan to build infrastructure over the next five years. It got a windfall from the central bank in excess of $24 billion to help finance its spending.

The Reference Shelf

- Festival of Lights fails to revive India’s sullen ‘animal spirits.’

- QuickTakes on India’s troubled shadow banks and the default of IL&FS.

- Oxfam International examines India’s extreme inequality.

- A look at India’s contentious GDP numbers.

- Bloomberg Opinion’s Andy Mukherjee assesses India’s broken tax system and the government’s growth plans.

--With assistance from Grant Clark.

To contact the reporters on this story: Vrishti Beniwal in New Delhi at vbeniwal1@bloomberg.net;Anirban Nag in Mumbai at anag8@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Nasreen Seria at nseria@bloomberg.net, Paul Geitner, Karthikeyan Sundaram

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.