Investors Shun Indian State Bonds as Lockdown Slashes Revenue

India’s states are being forced to borrow more to pay for spending to combat the coronavirus crisis

(Bloomberg) -- India’s states are being forced to borrow more to pay for spending to combat the coronavirus crisis, while at the same time facing rising debt costs that’s putting their finances under even more strain.

The Reserve Bank of India has cut interest rates and injected more than $50 billion in liquidity since last month to help drive down borrowing costs in the economy. Yet, in an auction earlier this month investors charged a significantly higher premium to buy states’ bonds, highlighting their uneasiness over the deteriorating finances of regional governments.

That’s a double whammy for the nation’s 28 states, which already face severe revenue pressures because of delayed payouts from the federal government and a halt in economic activity following the coronavirus outbreak.

The states gave up the bulk of their tax-making powers to the federal government in 2017 in return for a share of revenue from a nationwide sales tax. Punjab, home to 28 million people, says it’s still waiting to receive its share for the fiscal year that ended in March so that it can pay salaries and keep the state government machinery going. In addition, the 40-day lockdown to contain Covid-19 has cut states’ tax income from fuel and alcohol sales and real estate transactions.

At an auction held April 7, states were charged a spread of 133-173 basis points above the 10-year federal government bond yield of 6.42% prevailing at the time. That was higher than the 109-114 basis-point spread at the previous sale on March 30.

As a result, large Indian states such as Andhra Pradesh didn’t accept any bids for the 13- and 14-year maturity debt, while Punjab declined offers for the 10-year notes. The provinces of Gujarat, Kerala and Rajasthan accepted only part of their bids.

State finance ministers, like Kerala’s Thomas Isaac, were left disappointed after the sale, as they were hoping for the RBI’s monetary easing to lower their borrowing costs.

States are calling for budget rules to be relaxed, including easing a fiscal deficit cap of 3% of state’s gross domestic product and for the central bank to purchase their bonds, either in the market or directly from the government.

“The RBI should also consider buying state government bonds under its open market operations,” said A Prasanna, chief economist at ICICI Securities Primary Dealership in Mumbai. “States are sovereign as well and it would be dereliction of duty if the RBI and the federal government decide to force a cash crunch on states.”

Bigger Hit

Punjab, which pegged its deficit at 2.82% of state GDP for this financial year, is now staring at a tax shortfall of as much as a quarter of its 880 billion-rupee ($11.6 billion) revenue target, the state’s Finance Minister Manpreet Singh Badal said.

Plunging oil prices are another headache for states, reducing their royalties earned on crude production. States received about 40% of the petroleum sector’s total contribution of 5.75 trillion rupees in the fiscal year that ended March 2019.

In addition, lower fuel taxes from a slump in demand will probably result in an annualized loss of as much as 350 billion rupees for states in terms of fuel revenues, said Rahul Bajoria, an economist with Barclays Plc in Mumbai.

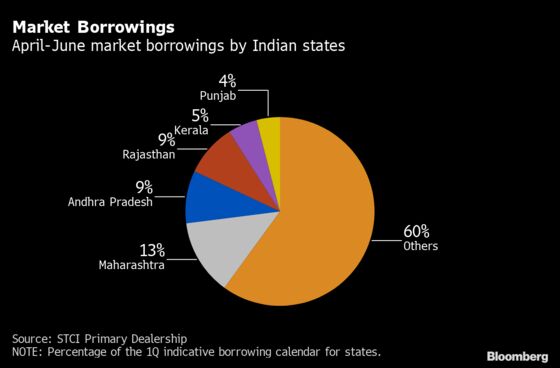

To plug the shortfall, states have front-loaded borrowings, raising almost 600 billion rupees in April, compared to 295 billion rupees in the same month last year.

“The situation needs to be looked into,” said Arvind Mayaram, a former top Finance Ministry bureaucrat for the federal government and now an adviser to the western state of Rajasthan. “It is expensive for states to borrow,”

The central bank has stepped in and increased states’ access to short-term cash requirements -- also called ways and means advances. While that has provided some comfort, borrowing costs remain sticky, putting the onus on policy makers to do more.

Samiran Chakraborty, Citigroup Inc.’s chief India economist, estimates the fiscal deficit for states will reach 4% of GDP this year compared with a target of 2.4%. That would push up the consolidated budget gap of the federal government and states closer to 12% of GDP, he said.

That’s not good news for policy makers, who are trying to open up the government debt market to foreigners, with plans to get India included into global bond indices. The ballooning deficits could also hasten a credit rating downgrade to junk.

Despite attractive yields on states’ debt, there’s tepid interest from global funds, which have used only 1.1% of the 715-billion rupee investment limit available to them in such notes. Even domestic investors are cautious.

“At this point we are avoiding state bonds. It is better to avoid uncertainty,” said Pankaj Pathak, fixed income fund manager at Quantum Asset Management in Mumbai. “We will see increase in borrowings. My view is yields will quickly move up.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.