The Agony of Caring for a Dying Parent During the Pandemic

Life in isolation is complicated enough, but the onslaught of Covid-19 is especially terrifying for the elderly and ill.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Every day now, I go to visit my father and mother in a care home in the English home counties, where they have retreated to what we all hope is a kind of safety from the Covid-19 coronavirus. And every day, as I walk into the building, perform the three-stage hand-disinfection process, and have a temperature gun pressed to my forehead, I feel guilt: No one should be allowed in to visit, and yet I am glad they make an exception. I have been isolating for weeks, my father is in the final stages of brain cancer, and I love him. I do not want to miss a day.

Losing your parents is inevitable and never easy; all adults know this. But in the time of this coronavirus, it is hard to describe just how much more complicated and fearful that process has become. Policy makers, as well as politicians and commentators brave or foolish enough to scream tactical advice from the sidelines—whether to risk the economy by closing businesses, or build “herd immunity,” or isolate only the U.K.’s 1.5 million most vulnerable—need to understand how this vicious circle works.

They need to understand because it dooms to reversal or irrelevance such responses as “America isn’t built to be shut down” and “THIS IS WHY WE NEED BORDERS!” that U.S. President Donald Trump has sent from his Twitter account. So, too, the denials from U.K. government officials that London might be locked down, like Paris and some other capitals on the continent, because the U.K.—“a land of liberty” as Prime Minister Boris Johnson put it—is not that kind of country.

On March 23, the U.K. nevertheless announced a partial lockdown of the capital, shortly after shuttering the schools it had said would stay open just a week before. As for borders, the Trump administration shut them only after the virus had arrived and then was slow to test and track those arriving with the disease. The only borders that matter now to my parents and millions like them around the globe are those between themselves and the rest of humanity. Isolation is impossible when you need care.

I have been helping my mother and sister, a former nurse, to look after my Dad at home since February, when he received the news we hoped would never come: His cancer had returned and was no longer treatable. Long before self-isolation became a thing in the U.K., we were self-isolating in their three bedroom apartment.

It has been brutally sad, at times also joyful. When we wheeled my father to meals, the four of us retold family stories repeated, no matter how often, over the years and cried with laughter. My mother took him on “trips” they’ve been on together and won’t make again. “Where would you like to go today?” she’d ask. Yellowstone was a favorite. And each time my sister lifted him in or out of bed, using an old-school double “bear hug” maneuver, he’d pat her back affectionately with his right arm wrapped around her.

Every morning while we tried to keep my father at home, we could hear the Macmillan nurses—a very special group of people from a charity that gives palliative care to late stage cancer patients—cackling behind the bedroom door as he jousted with them. But even they, the nearest that someone as irreligious as myself can imagine to angels, posed a threat. They could carry the virus to my parents, age 86 and 81, without even being aware they had it. Some had children in school, some had husbands and wives who worked and took public transport; all of them had to eat and therefore, to shop. So long as the government tried to mitigate rather than stop the disease, and life went on more or less as usual, they had to push the same shopping cart handles and press the same buttons of the “pay and display” parking machines as everyone else.

The same was true of the National Health Service’s district nurses who came to visit, of my parents’ doctor, of their friends from the apartment complex, and of my sister and me and our spouses and children. We began to isolate from our families and friends weeks ago. Yet, as my father became more ill and needed more help, even the morning nurse visits, combined with the devotion of my sister and mother—waking to help him as many as 16 times per night—were not enough. Forced to choose between shifts of agency nurses coming into the flat to care for him or having him go into a home, we asked my father what he’d prefer. As always, he went with what he thought was best for us: a home, where staff could look after him.

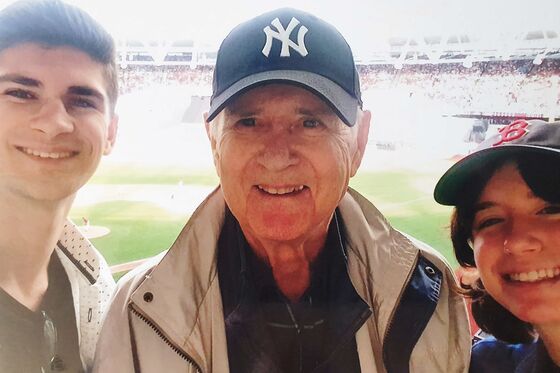

A New Yorker marooned among Brits since 1968, my Dad may have lost the use of his left side and other functions in recent weeks, but the ease, curiosity, and humor he’s always had with other people remain. He wants to know where the home’s nurses and caregivers are from; in most cases, he’s been there. He ran cargo all his life, first on trucks through Europe to the former Soviet Union and Iran. (He was in Tabriz when the revolution struck.) Later, he built a small company that organized freight on passenger planes to all points, from Thailand to Cuba. He contracted Russian aircraft with Ukrainian pilots to drop food aid in Africa. His caregivers mostly have native English accents, but their origins are in Benin, Latvia, Spain, Zimbabwe, and pretty much everywhere else. Working nonstop across 12-hour shifts, they are extraordinarily kind. He invents nicknames for them, rather than use the ones on their badges. One petite nurse is “Muscles.” A burly male caregiver is “Skinny.”

The home is beautiful and probably more locked-down in terms of hygiene than the rotations of agency nurses we would have had to rely on at home. Even so, it poses the same threats. There are about 30 patients, as well as 50 caregivers and nurses, plus cooks and other staff to look after them. They all live out in the world, and all have to eat and shop, even in the age of online deliveries. “Muscles” has five children.

My mother checked herself into the home, too, so she could be in the same room with my Dad at night, when he’s most anxious, to help him and hold his hand. It was their 60th wedding anniversary last year. “She pokes,” my father says. The other night, she called me, distraught after watching a TV news item about a care home in the next county, where this coronavirus had ripped through the building and infected three quarters of residents. “It’s like being on one of those cruise liners,” she said, worrying that we might have made the wrong choice and that she and my father could become trapped in a fatal petri dish of Covid-19. Her care home has since told its residents they are confined to their rooms, to prevent mingling in the common areas.

Of course, there's a debate even among epidemiologists about just how different this coronavirus is from the flus that kill tens of thousands people every year. Given that every country so far has imposed radical measures to slow the spread of the virus once hit, we may not know for years what happens if you don't. Yet the doctors who have struggled, and in some cases died caring for patients in China and Italy seem pretty convinced that Covid-19 is very different indeed.

For my parents and for thousands, if not millions, of others in our aging societies, there are no safe choices while the herd is getting immunity. There is no way to separate the elderly and vulnerable from the general population because they need younger, healthier people to care for them. The only way to stop them dying in numbers is to dramatically slow the spread of the virus through the population as a whole, a conclusion that some countries have come to sooner than others. China, after initially doing everything possible wrong, halted the spread by cracking down decisively on movement and mingling. South Korea also seems to have turned the tide through mass testing to track and block the spread of the disease. Italy has discovered the cost of being behind the curve, of trying to balance human life against personal freedom and economic pain; only now, after a nationwide lockdown made more devastating by its delay, has the death rate stopped accelerating.

The U.K. and the U.S are catching up. Whatever their leaders may have said before, as the death toll begins the same geometric climb seen elsewhere they have found that theirs, too, are the kinds of societies that are ready to curb personal liberties. They, too, have started locking down life and business and no doubt will keep doing so for as long as it takes to get the contagion under control. Because it's that kind of disease.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.