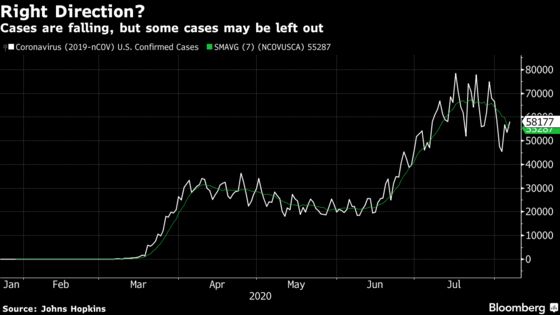

Covid Cases Go Undercounted With Muddy Data From U.S. States

The number of Coronavirus cases might not be reliable.

(Bloomberg) --

After a spiraling coronavirus outbreak that pushed California to the most infections in the U.S., the trends appear to be brightening: Daily reported cases have plunged, as has the rate of tests that come back positive.

The trouble is, it’s unclear if those figures are accurate.

California officials have uncovered a bug in their virus reporting effort -- the nation’s largest, with more than 120,000 people tested each day. On Monday, Governor Gavin Newsom touted a 21% drop in the average daily rate of new cases from the prior week as a sign of stabilization. The next day, his top public health official warned the numbers were likely too low -- by how much he couldn’t say -- and the state didn’t know when the problem would be fixed.

The glitch doesn’t affect the accounting of deaths and hospitalizations. California on Friday became the third state to lose more than 10,000 people to the virus, behind only New York and New Jersey. But hospitalizations have fallen 17% from a July 21 high, perhaps a sign that the current surge is peaking. Without confidence in the number of new cases, officials can’t quite be sure what’s going on.

“We don’t know if our cases are plateauing, rising or decreasing,” Sara Cody, public health director for Silicon Valley’s Santa Clara County, said at a press briefing. “I would say that right now, we’re back to feeling blind.”

Months into fighting the pandemic, officials across the country are still struggling with some of the most basic, necessary steps: spotting infections, counting cases and reporting deaths. Testing is so chaotic that a coalition of seven governors on Tuesday announced they would try to create a nationwide program from the ground up, roping in every state willing to join.

Florida -- home to the second-most U.S. cases -- briefly paused its own testing program due to Hurricane Isaias, a disruption that could happen again in storm-prone states as the heart of the hurricane season nears. Texas, meanwhile, has adjusted its data-collection methods several times for both new cases and death counts, at one point sending its reported fatalities surging 13% in one day.

Tracking the trajectory of the outbreak is key: States trying to restart their economies need accurate, up-to-date numbers to monitor their progress against the pandemic. So do school districts debating when to allow students back on campus. And “contact tracing,” calling people who may have come into contact with an infected person, is impossible without fast results.

“We’re trying to walk this tightrope of keeping as much business open as possible without letting this thing explode,” said Carl Bergstrom, a biology professor at the University of Washington in Seattle. “We need data that’s both accurate and timely.”

That said, such problems may be inevitable in a pandemic of this scale. “Coming up with timely, high-quality aggregate statistics is just plain hard,” Bergstrom said.

Data ‘Stuck’

California officials have not yet described in detail what has gone wrong with their case reporting system. Mark Ghaly, the state’s Health and Human Services secretary, reported the problem during a Tuesday briefing, saying it appeared that data sent from testing labs to the state was “getting stuck.” Officials have been working “around the clock” to fix the issue, he said in an emailed statement Thursday.

“We will not rest until this problem is resolved,” Ghaly said. “All Californians and local public health officials must have accurate data, and we pledge to share a full accounting of when these problems began and their magnitude as soon as we have a clear understanding -- and the solutions to address them.”

County health officers don’t even know how far back the undercounting began. Cody said the bad data may reach back to mid-July.

California has seen its daily case count decline from a peak of more than 12,000 two weeks ago to just 5,258 on Wednesday, though it climbed to 8,436 yesterday. Ghaly said Tuesday that while the data glitch may be undercounting new cases, the more accurate hospitalization numbers were encouraging.

“We feel confident that they are beginning to stabilize,” Ghaly said.

Florida Uncertainty

In Florida, all state-run drive-through and walk-up testing sites were closed last week in anticipation of Hurricane Isaias, cutting overall testing capacity dramatically and artificially slashing new reported cases on Monday to the lowest in more than a month.

With the case data muddied, analysts were left to scrutinize positivity rates and hospitalizations, measures that appear to signal improving trends but have issues of their own. Speaking Tuesday in Jacksonville, Governor Ron DeSantis raised questions about his own state’s positivity rate, a data point he had previously promoted but that’s recently been at stubbornly high levels, undermining his case for restarting schools.

“Some labs don’t report the negatives religiously; sometimes they do data dumps,” he said. “I’d be very cautious of tying a child’s future to the efficacy of some private lab dumping the results into a system.”

His concerns about unreported negatives -- which would shrink the denominator in the ratio and theoretically inflate the rates -- appeared to echo a Fox 35 Orlando report last month. In a response at the time, his own Department of Health confirmed that some “smaller, private labs” were wrongly failing to report negatives, but that the state had immediately contacted them to rectify the problem. To be sure, Florida’s cumulative positivity rate appears broadly similar even if you exclude all smaller labs.

Texas has made data revisions rippling back through March that make historical comparisons difficult. At the end of July, the state decided to change its data source for fatalities, relying on the cause of death listed on death certificates instead of local government reports.

But since coroners and hospitals are given 10 days to file those certificates to the state, that’s resulted in a two-track death count: a daily measure of how many virus deaths are reported on the certificates received by the state each day, and a count based on the actual date of death that is in constant flux for every rolling 10-day period, making it difficult to gauge the true toll.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.