Biotechs Are Battling to Make the First Good Blood Test For Covid-19

The antibody tests are at the forefront of a push to assess who has unknowingly built up potential immunity to the new virus.

(Bloomberg) --

When Gunther Burgard read about a new coronavirus spreading in China in early January, he convened his team at PharmAct AG to find out whether the biotech’s platform of finger-prick diagnostics could be put to work in the outbreak.

The Berlin-based company uses markers in the blood to detect everything from heart attacks to early signs of diabetes, offering results in less than 20 minutes. Harnessing that experience to find Covid-19 antibodies seemed within reach, says Burgard, PharmAct’s medical director.

Four months later, PharmAct’s $40 test kit—and many others like it from enterprising startups and established players around the globe—are one tool that could allow governments and scientists to grasp the pandemic’s true scope.

These antibody tests are at the forefront of a push to assess who has potentially built up some immunity to the new virus, even unknowingly, pinpointing who can probably leave confinement and start rebuilding shattered economies. But the technology is harder to get right than for basic diagnostics, and the new tools proved unreliable in the U.K. and Spain, raising questions about whether the race to supply them has come at the expense of quality.

“Every scientist and his dog is trying to make this test,” said James Gill, a clinical lecturer at Warwick Medical School in Coventry, England. “Whichever one is the fastest, whichever one is the cheapest, and whichever one is most reliable will be adopted.”

PharmAct’s test, intended for healthcare professionals, suffered a public relations blow shortly after it went on sale last month, when a prominent virologist told a German newspaper that he had used it for research in the country’s biggest coronavirus hotspot and that it had failed to catch two-thirds of cases.

“That hurt us a lot,” Burgard said. “It was written all over that these tests are rubbish.” He calls that analysis “bad science,” arguing that his company’s test can’t identify infection early on, since people have yet to build up antibodies. The virologist’s sample size was also too small to be instructive, he said.

Still, PharmAct is working on improving its test, which has millions of orders beyond Germany’s borders, according to Burgard. By his own estimates, the test is reliable more than 99% of the time.

Adding to the attraction, the antibody tests are easier to mass produce and handle than the ones currently used to diagnose patients while they’re infected, since they have fewer components and often don’t require skilled lab technicians.

Swiss giant Roche Holding AG said Friday it's introducing its own version of an antibody test in early May and monthly production of it could reach the high double-digit millions by June.

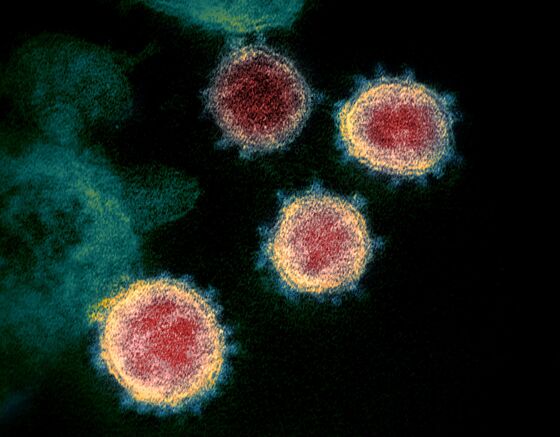

The scramble to make the new tools kicked off on Jan. 10, when Chinese researchers published the genome sequence of the new virus. That enabled scientists to analyze its molecular structure, which includes about 29 identifiable proteins.

Antibody test makers have chiefly focused on two of those: the spike protein that sticks out of the virus, giving it its crown-like shape, and one called a nucleocapsid, which is located inside and surrounds the virus’s genetic material.

When a person gets Covid-19, their immune system summons antibodies to neutralize the virus’s proteins. So a reliable test needs to contain proteins—grown in the lab—that are as similar as possible to the virus’s natural ones. (The test’s accuracy also relies on other factors, such as the selection of chemical buffers).

The publishing of the genome sequence brought about a crucial decision for test developers: should they grow the viral proteins in their own labs or buy them from a biotech supplier? The latter option was compelling, since it’s often faster and cheaper, but it comes with a risk.

That’s because a company might order a bad batch of proteins, stick it on their test and only discover weeks later that it’s compromising results. Still, many are willing to take that risk in order to speed up development.

“If you’re a company, you have about 40 competitors doing the same thing, and quickly,” says Stanley Perlman, a microbiology and immunology professor at the University of Iowa’s Carver College of Medicine. “I’d want to do everything myself.”

PharmAct started out by buying proteins, but it’s now making as much of them as possible on its own.

Once a test is made, the hard part comes—proving that it actually works. To do so, researchers check how the test performs when looking at two categories of blood: some that’s Covid-19 positive, and some that they know isn’t.

If a test can reliably identify positive samples, it’s considered highly sensitive. If it can identify negatives, it’s called specific. That means it knows the difference between Covid-19 antibodies and others raised by, say, another coronavirus that causes the common cold.

Validating the serological tests has been hard. Early on, the Chinese health care system at the heart of the outbreak was so overwhelmed that test makers operating there struggled to access blood samples of patients. That was even more difficult for companies located elsewhere.

“It was virtually impossible to get blood samples out of China,” said Volker Stadler, chief executive officer of PepperPrint GmbH, a diagnostics startup in Heidelberg, Germany, that’s developed a so-called peptide microarray to scrutinize the actual bits of protein to which antibodies attach—a level of detail that could help developers make even more discerning tests.

Things got easier after a small outbreak of Covid-19 hit Munich in late January. Blood samples from 14 patients traveled to Berlin’s Charité hospital, and PepperPrint was able to send a technician there to test its research tool. The company has also started developing its own antibody test.

Most test developers tout their products as performing very accurately when properly used, according to Marco Donolato, co-founder and chief scientific officer of BluSense Diagnostics ApS in Copenhagen. “If you see the brochure of every company, it’s 99%,” Donolato said.

In reality, the tests often don’t perform so well in the hands of inexperienced users who are often toiling in sub-optimal conditions. BluSense is working to validate its own antibody test with blood samples in Denmark. The process is often iterative, with test-makers tweaking their kits gradually to improve accuracy.

An impartial review of dozens of antibody tests will be available in coming weeks from the Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics, a nonprofit group based in Geneva. PharmAct’s test isn’t among them, though the organization plans to keep investigating more candidates on a rolling basis.

Gill, the lecturer at Warwick Medical School, has a rather clear picture in his head of what a winning product should look like.

“If your test can be dropped down the stairs by a health-care worker who has fumbled the box, and be left on a counter in Nairobi in the blistering heat, and be dunked in a river accidentally in America,” he said. “If your test can survive all that and give the accurate result, your lab is going to make an awful lot of money.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.