Dining Out, Digitized

Many restaurants dropped printed menus during the pandemic in favor of QR codes. Will eating out be the same?

(Bloomberg) -- Add the analog menu — soggy from wet glasses, or ketchup-stained — to the long list of things the pandemic disrupted.

Although by now there’s scant evidence that germy surfaces aided the transmission of Covid-19, thousands of eateries across the globe responded to the threat by introducing touchless, digital ordering. Diners venturing back into restaurants that have re-opened to full capacity are often finding that some familiar icons of the eating-out experience — leather-bound wine lists, card-stock notices offering daily specials and signature cocktails — are missing. They’ve been replaced by black-and-white QR codes posted on tables and mounted on walls.

Intuitive for many internet-savvy guests, harder to swallow for older patrons, digital menus are changing the experience of eating out. When scanned with a smartphone camera, QR codes direct patrons straight to a restaurant’s website, or the landing page for a digital menu. The technology is not a pandemic invention: QR — short for “quick response” — codes were created in 1994 and caught on first in Asia. Scanning them in the U.S. required a special application, and for decades the grids were “widely seen as unsexy, even a hassle,” as the New York Times’ Lora Kelley wrote. But in 2018, Apple put the QR code scanner right into the camera and using them became more intuitive. Now, a global catastrophe has helped make these patterns ubiquitous.

“For an operator, they never really imagined a world where they didn’t have to print menus. And then you show them that world, and they’re like, ‘I’m not going back,” says Kim Teo, the CEO and co-founder of Mr. Yum, an Australia-based company that develops QR code menus and ordering systems for cafes and restaurants. Launched in 2018, Mr. Yum grew 27-fold in 2020, and closed an $11 million funding round in April 2021. Pre-Covid, just 100 restaurants in Australia used the platform for take-out and in-house ordering; that number has since surged to 1,200 globally, and the company is expanding into restaurants in the United Kingdom and across the U.S.

As the restaurant industry recovers from the pandemic, which forced 10% of the nearly 800,000 U.S. establishments to shutter in 2020, restaurateurs are rethinking longstanding practices in an effort to trim overhead and keep workers and patrons safe. But the printed menu may not go away quietly.

The art of menu engineering

Menus have been found in Song Dynasty-era China and ancient Greece, but they didn’t emerge en masse in the Western world until the 1770s, when restaurants — considered restorative spaces for the upper-class — hit the scene in France. “Previously, if you were traveling, and you stopped at an inn, and if you were lucky, and you got there around the time that people ate dinner, the innkeeper might give you dinner, but it would be pretty much whatever he had,” says Rebecca Lee Spang, a professor of history and the author of The Invention of the Restaurant. “Restaurants said, well, you can have a choice.”

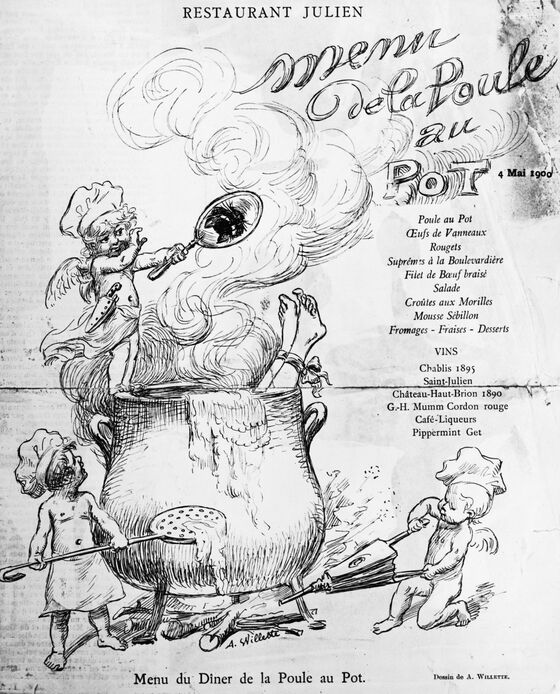

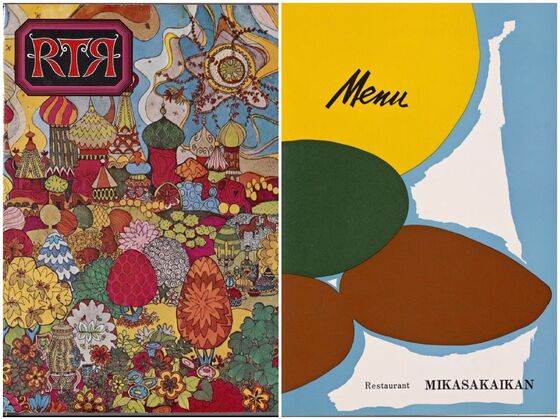

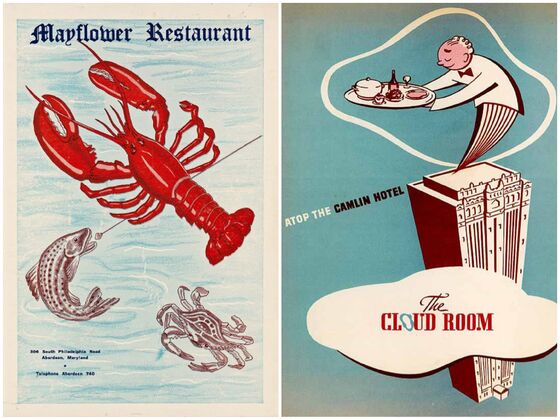

From the 1800s up to 1840, early menus — a French term for a small, detailed list — looked a lot like newspapers, with the wine list printed along the bottom, where the serialized novel would usually go, she says; later, they looked more like paperbacks; new printing technologies of the end of the 19th century ushered in elaborate Art Nouveau menus illustrated by artists like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. In the 20th century, menu design reflected changing cultural tastes and the rise of eating out as an option for a growing urban middle class; the post-war era brought spill-proof plastic lamination, fun novelty shapes, and kids’ menus; the 1960s featured psychedelic graphics. By the late 20th century, the menu had become a dining staple, a computing tool, and a synonym for “choice.”

Beyond their immediate functionality, menus have also always played a key role as marketing objects, says Alison Pearlman, a professor of art history and the author of May We Suggest: Restaurant Menus and the Art of Persuasion. The 1920s advent of “scientific management” applied to businesses brought renewed attention to the language menus used, and the early 1980s introduced the concept of “menu engineering,” which focuses “on maximizing the profitability of menu ‘real estate.’” Psychologists and color experts consulted with restaurants on how best to direct consumers’ eyes and lure them into spending lavishly. In his book Priceless, William Poundstone unpacked the behavioral science engineered into menu design, with high-profit items and super-costly “anchor” dishes listed on the eye-catching top right corner, so that less-expensive entrees will appear more affordable in comparison. (Unprofitable dishes, meanwhile, get exiled to “menu Siberia.”)

Cocktail menus are often provided by alcohol distributors themselves, who develop copies to give to restaurants. In exchange for handling graphic design and printing for bars and eating establishments, the alcohol distributors can control the order and placement of cocktails in the book, elevating certain flavors and drinks.

Pre-Covid, some of this marketing activity had already migrated online; restaurants have been building out their websites since the early days of the World Wide Web. But when the pandemic hit, establishments that already had a robust digital presence were better equipped to manage the sudden shift to take-out only. In those early days, BrandMuscle, the U.S.’s largest purveyor of alcohol marketing materials and menu books, launched a new product called SpotMenus, which allows restaurants and bar owners to create custom QR-code based menus and host them. By now, more than 5,000 establishments across the country have turned their menus digital with BrandMuscle, and menus are being shown online every minute of every day.

The advantages of online menus and ordering platforms are obvious: At a time when food supply chains have been disrupted, QR codes offer flexibility. “In the print world, it would be very expensive and cumbersome to keep printing your menus,” says Richard Mendis, BrandMuscle’s chief strategy officer. “In the digital world, it’s a couple of clicks and you’re done.”

Some restaurant staff agree. Digital menus are one less thing to clean and clear each night, say servers and bartenders I talked to recently in New York and Minneapolis. Seasonal menu changes don’t have to come with the sacrifice of trees. Restaurants can show a special brunch menu on Sunday morning and another one on Wednesday, using the same QR-generated link. Instead of black marker edits on laminated menus, restaurants can hike prices without drawing attention to the change. (“It’s hard to get angry about something you didn’t know happened,” says Spang.)

Russell Jackson, the head chef and owner of a California-style fine-dining restaurant in Harlem called Reverence, never had a printed food menu, or even a direct telephone line into the restaurant: Reservations are made online, or by scanning a QR code affixed to the front door.

This reliance on technology wasn’t born out of Covid. Lafitte, Jackson’s San Francisco restaurant that closed in 2012, had a video feed aimed at the kitchen and front of house to increase transparency; the restaurant was one of the first to adopt iPad menus in 2010. Digital menus helps him avoid one of his own pet peeves: “To be told, ‘Oh sorry, we’re out of that, we don’t have that bottle’ drives me f---ing bonkers,” he says. “I never wanted somebody to have that kind of experience in one of my restaurants.”

But Spang, the author of The Invention of the Restaurant, finds the act of whipping out one’s electronic device to begin or punctuate a meal disruptive. “It makes the whole thing so solipsistic,” she says. “There’s no communication. It really does make the people serving the table less and less like people — and more and more like robots.”

A death knell for servers?

Jesse Johnson, 66, has worked at the San Francisco International Airport for 40 years, 33 of them spent as a bartender. He’s also on the executive board of the labor union Unite Here, where he serves as a shop steward. After a year of living off unemployment during a pandemic furlough, Johnson was eager to return to his $15.10 an hour job at SFO’s Union Street Gastropub in June. But management of the bar, the global company SSP America, proposed a restructuring plan, laying off servers and allowing customers to order drinks via QR code menu instead.

While Johnson’s role mixing drinks would be safe, he and other union representatives pushed back on the plan. Decades ago, Johnson worked on an assembly line on an auto plant, he says, so he knows what happens when automation comes for good-paying jobs; he’s worried that other airport restaurants may reduce full-service options in response, he says. “Sooner or later they’ll be coming for you, in some form or another,” he says.

Management responded by continuing to delay the restaurant’s reopening date. (SSP America did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

Labor shortages in the hospitality industry mean that restaurants are scrambling to hire back staff fast enough, making the streamlining of ordering an attractive fix. But workers like Johnson, who are eager to return, see the potential of pairing QR code menus with new digital ordering and payment systems as a death knell for servers. Mr. Yum’s Teo says that while digital ordering has been slower to catch on in the U.S., it has “really heated up in the last three months.”

Suzy Liebowitz, who’s worked at Winfield’s Restaurant and the Gazebo Bar & Grill at the Hyatt Regency in Greenwich, Connecticut, for two decades, has been caught in limbo for the past year as she waits to know whether her pandemic layoff will be made permanent. Already, room service at the hotel has been replaced with a to-go option that involves online ordering and delivery fees that colleagues say cuts into tips; management has told her Unite Here union chapter that the still-closed Winfield’s is weighing a similar transition. The Hyatt did not respond to requests for comment.

“The hospitality industry is trying to get back to full occupancy without ever bringing back its full workforce. That’s bad for workers and guests, because restaurants are using Covid-19 as an opportunity to eviscerate jobs and cut services, and when you think about a restaurant without real hospitality, that’s almost like a college dorm experience,” said D. Taylor, the president of Unite Here, in a statement. “Servers, bussers, hosts, bartenders, and more are the backbone of the service economy, and taking these jobs away means that many working families and especially communities of color might never recover.”

Restaurant labor organizations seem to recognize that the introduction of features like QR codes could herald broader automation. Culinary Union, which represents 60,000 hospitality workers in Las Vegas, built a technology clause into their contract in 2018, stipulating that every time a restaurant brings in new tech, workers need to be notified in advanced, and involved in the roll-out. “Hospitality jobs will continue to change and evolve as they always have,” a union spokeswoman said in a statement. “The Culinary Union’s innovative technology language ensures that workers can grow with technology, have a seat at the table, that new technology is implemented in a worker-centered way, and that workers have the opportunity for job training or re-training in order to access any new jobs created due to technology.”

Jackson, the head chef at Reverence, says tech should be welcomed, not feared, by servers, because it lets them do their jobs more quickly and focus on other elements of hospitality. He compared it to Bruce Lee demonstrating Jeet Kune Do, his martial arts fighting style. “He said, I’m taking classic karate, and I’m cutting away all of the dance moves and all of the superfluous movement and steps. And I’m going straight to the power,” he says. “I’m being efficient with my actions and my energies and not wasting. That’s the core mandate of what we’re doing.”

A menu that looks back at you

There’s another thing about dining technology that might give patrons pause: When you look at an online menu, the website begins to track you, too, opening up a new universe of behavioral nudges and menu engineering options. “In this phase, menus merge with data streams,” says May We Suggest’s Pearlman.

On sophisticated websites, restaurants are able to tell how many people are looking at their menus, for how long; where their eyes linger and whether people ever scroll down to dessert. (The top 5% of any given menu gets two and a half times more clicks than the next 5%, says Mr. Yum’s Teo.) Restaurants can use the information they glean online to influence their food offerings, or fine-tune the order of the food they list.

That means that scanning at a menu in a restaurant might soon be a little bit more like scrolling Facebook: Sponsored content and featured drinks and dishes custom-tailored to guests based on their browsing history are not far away, says Sly Cosmopolous, the director of beverage marketing for Republic National Distributing Company. “I think it’ll just be a lot more advancement and offerings above and beyond just being able to scan and look at a menu,” she says.

Cosmopolous says she wouldn’t advise restaurants get rid of all printed options — there are always going to be the phoneless, or the phone-averse, and to bridge a language gap, nothing beats pointing to the words on the page. Many fine-dining restaurants have not hesitated to bring their handsomely bound menus back. But even this incomplete transition to online ordering has triggered some preemptive nostalgia among those who fret that dining is losing something essential.

Jan Whitaker, a writer and restaurant historian who writes the Restaurant-ing Through History blog, uses old menus as a primary source, and a visual guide through the evolution of eating out. At antique book and collectibles shows, she often leafs through menus that had been taken home by guests, creased in the middle to stash in pocketbooks or signed by the diners as a souvenir. Each tells a story about some long-lost special occasion

When she first saw the barcode displays, she figured they’d be a temporary “desperation measure.” Like the plastic igloos in which winter diners huddled, she assumed they’d disappear when the threat of Covid passed. “If everybody were to go [digital], it would be very boring,” she says. “I don’t know if it would hurt their bottom line, but they would lose a big chunk of what gave restaurants a certain character. They would lose some richness, I think, that the printed menu can have.”

She’s not convinced that the time- and labor-saving efficiencies that the new technology promises are worth this trade-off. Removing the act of browsing a physical menu runs the risk of removing some of the timeless mystique of dining out.

“I think the restaurant always treads a little bit on dangerous ground when it tries too much to rationalize the system,” she says.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.