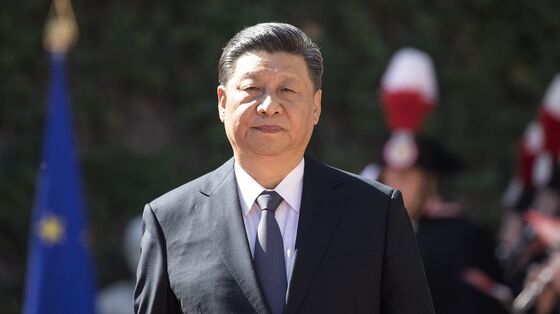

Xi’s Toughest ‘Common Prosperity’ Test Is Raising China’s Taxes

Xi’s Toughest ‘Common Prosperity’ Test Is Raising China’s Taxes

(Bloomberg) -- Whether silencing Hong Kong dissent or countering U.S. sanctions, China can move faster than almost any country in the world to approve complex legislation.

That’s why the yearslong delay to pass sweeping property tax reform, called “crucial” by a top official in 2018, is so telling. The Chinese legislature’s most recent five-year agenda made drafting a real estate tax a priority, but now, more than halfway through, President Xi Jinping’s recently announced property tax plans fall far short of what lawmakers hoped.

As part of the “common prosperity” campaign, which seeks to promote economic equality and narrow China’s wealth gap, the government announced that it will initiate a series of local property tax pilots. Hainan, which is being turned into a free trade hub, and model socialist city Shenzhen, are considered among the likely candidates.

It’s the latest baby step toward tax reform, to which Beijing has aspired for years without much success. With one-party control and little overt political opposition, using the tax code to advance social policy wouldn’t seem so difficult. But the Communist Party is sensitive to public opinion, particularly among the middle class, and taxes are as politically fraught in China as they are anywhere else.

In 2013, China’s top governmental body called for broader property taxes and moving toward an inheritance tax, according to an official notice. Months of internal debate downgraded the recommendations from guidelines to “opinions.” To further weaken their impact, the State Council released them right before the country’s busiest holiday.

“All the sharp corners were smoothed out,” said Jia Kang, director of the China Academy of New Supply-side Economics and the former head of the Ministry of Finance-backed Chinese Academy of Fiscal Sciences which was a party to the talks.

Beijing’s latest move on property taxes shows how much Xi relies on the support of China’s massive middle class, which in turn has gotten richer under his leadership. The government hasn’t wanted to alienate them with unpopular new taxes, but if it grows bolder, here’s what it might do:

Property tax

Beijing has long been trying to establish a national tax on real estate, which for city dwellers represents roughly 70% of their household wealth. A property tax would effectively be a wealth tax, with the potential to stabilize prices in the country’s hottest housing markets.

Soaring home prices, though, have enriched local governments. Land sales generated about 35% of their income in the first nine months of 2021, so they resist any measures that could suppress real estate values.

Central government officials tried to reassure the public the purpose of the register was not to levy a property tax, and the project wasn’t finished until 2018 -- the same year China’s top legislature made property taxes a priority in its five-year agenda.

Opponents to such levies are “not only broad but powerful,” Macquarie economists Larry Hu and Ji Xinyu wrote in a note last week. They are “much more than a wealth redistribution from rich to poor, but from older generations and high-tier city residents to the rest.”

Whether the taxes would even work as designed is an open question. A decade ago, Shanghai introduced a property tax of 0.4%-0.6% for newly purchased homes and for local residents’ second homes. The levies generated more than 19 billion yuan in municipal revenue last year, just 3.4% of total local tax income and less than 7% of the amount generated from land sales in Shanghai last year, according to Hu and Ji. Meanwhile, home prices in the city have continued to soar.

Bottom line: Beijing will settle for local pilot programs for now.

Income tax

China overhauled its individual tax system several years ago to ease the burden on lower-income earners and boost overall consumption. But the system still favors the rich, taxing business and investment income at much lower rates than personal income tax rates.

That’s an easy target for change, said Jason Mi, a tax partner at accounting firm EY. “The main source of income for high-income individuals is business income, income from studios, which could all be included into individual income tax in the future,” he said.

At the same time, China may lower the overall rate, including on wages and salaries, from 45% to 35%, a measure that aims to encourage the middle classes, Shi Zhengwen, director of the Center for Research in Fiscal and Tax Law at China University of Political Science and Law, told state media.

China has managed to push through reform before on individual income tax. In 2018, authorities raised the income tax threshold from 3,500 yuan ($548) to 5,000 yuan per month and added new deductibles including children’s education and treatment for serious illness. Political and business leaders have called to further raise the floor to 10,000 yuan a month.

More recently, Beijing has emphasized enforcement, offering amnesty for people who owe back-taxes and making examples of high-profile celebrities such as Zheng Shuang, who was ordered to pay 299 million yuan in overdue taxes, fees and fines in August.

Bottom line: China has shown a renewed determination to tackle tax evasion by the wealthy, but no clear time frame has emerged for further reforms.

From the Archives: China Issues Revised Regulations on Individual Income Tax

Inheritance Tax

China is one of only a few major economies that doesn’t levy an inheritance tax. Until recently, it didn’t need one, as there wasn’t much generational wealth to pass on. But the growing ranks of China’s millionaires and billionaires are increasingly interested in protecting their wealth for their children, while the government sees it as a way to interrupt long-term patterns of inequality.

The government first flirted with an inheritance tax in 1995, when the country’s tax bureau drafted regulations aimed at those with more than one million yuan, then worth about $157,000, according to reports in local media. Four years later, finance ministry officials said the inheritance tax law could pass as soon as 2000, but it never did.

Chinese officials last talked about an inheritance tax in 2013, when the State Council said it would study the measure. Still, rumors have swirled, and in 2017, state media encouraged the government to focus on the accumulation and pursuit of wealth, suggesting that an inheritance tax would just encourage rich people to move capital offshore.

The objections are practical -- there’s no system that could track or verify an individual’s assets -- but also deeply political. Before the rank-and-file would agree to pay, they might want to see senior government officials disclose their own personal fortunes, Jia Kang wrote in an essay on his personal Wechat account. That may be a deal-breaker.

Bottom line: If implementing an inheritance tax requires the wealthy to fully disclose their assets, it’s not on the table.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.

With assistance from Bloomberg