China’s Secret Children Step Out of the Shadows

Survivors of the one-child policy recall forced adoptions and derailed careers.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- As China enters a year that could finally bring an end to the world’s biggest social-control experiment, parents and children who suffered under the one-child policy are beginning to step forward to share their stories.

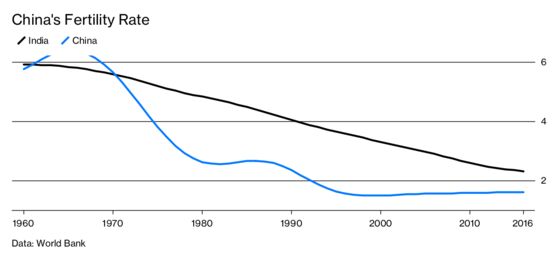

Introduced in the 1970s in a series of local trials that coalesced, after years, into a national policy, China’s birth restrictions fundamentally altered the fabric of its society. Communist Party officials say the one-child directive prevented 400 million births, though academics have argued that figure is too high, because the country’s fertility rate would have declined gradually without government interference, owing to factors such as improved living standards, rising education levels, and more women entering the labor force.

Despite the threat of hefty fines, forced abortions, and dismissal from public sector jobs, some Chinese couples chose to defy Beijing’s family planning edicts. There are no reliable estimates for how many children have been born illegally since the government began restricting births, but they likely number in the hundreds of thousands, if not millions.

“A public policy can only proceed smoothly if it is understood and supported by the public—or it must rely on coercion and violence,” says Zhang Zhihu, 54, who was fired from his teaching position in 2012 after fathering a second child. “The birth policy is the case in point.”

The challenge now facing China’s policymakers is how to reverse the policy’s legacy: an aging population with 30 million fewer women than men. In 2016, the government announced a two-child cap and has since moved to scrap birth limits entirely after an expected baby boom failed to materialize. The National Health Commission dropped the words “family planning” from its name last March, while China’s legislature removed references to regulations on family size from the latest draft of a sweeping civil code slated for adoption in 2020—the clearest signal yet that the policy’s days might be numbered.

With its end looming, some of the people whose lives were forever changed by the policy have been emboldened to speak publicly about their plight. Here are three of their stories.

“We are like strangers”

For Xie Xianmei, 28, the one-child policy has meant a life of wondering what could’ve been.

She was born to parents in the southwestern province of Sichuan who already had a child, just days after Beijing publicly warned local government officials that population control would be a key metric for assessing their performance. The local Family Planning Office gave Xie’s parents a choice: pay a 8,500 yuan ($1,600) fine—more than 12 times the average income for a rural resident—or give her away.

The infant Xie was “reallocated,” in China’s bureaucratic parlance, to a single father who paid 200 yuan—a sum he raised by selling two pigs.

Xie struggled in her foster home, mocked as the “picked-up girl” by other villagers. She dropped out of school at 14 and started a series of odd jobs around the country, from housekeeping to inspecting leggings at a factory. In 2013 she decided to track down her birth parents in Dazhou, Sichuan, after watching a TV show about sensational family reunions. “Was I abandoned or not?” Xie wondered. “I cared about the answer so much.”

Learning that she wasn’t has brought a new fear: that she may never share a loving relationship with her mother, even though they now live in the same city. “We are like strangers, and we don’t have much to talk about,” says Xie, now a housewife and the mother of a 1-year-old. “Life would have been completely different if I were growing up with my family. To my birth mother, I’m just an outsider and intruder.”

“My right to work shouldn’t be deprived”

Guo Chunping’s decision to have a second child cost him his career.

A onetime government bureaucrat in the central province of Jiangxi, Guo, 42, decided to tempt fate seven years ago after reading about the emotional and financial struggles of parents whose only child had died. “I thought to myself: What should I do if something happens to my only daughter?”

The threats came even before his second daughter was born, with local family planning officials urging the couple to terminate the pregnancy. Abortions were a central feature of the one-child policy, with many parents electing to abort female fetuses and others forced to terminate if they couldn’t pay the fine.

Guo not only paid a 124,000 yuan penalty, he was also fired from his job with the local finance bureau. His demands for a written explanation and compensation were ignored. He wound up teaching math at a local middle school, making $8,800 a year, about 40 percent less than his former salary. His wife’s income as a village doctor is half that.

For decades, public employees fired for flouting the one-child policy have agitated for restitution. In nine provinces, civil servants who have more than two children still face the risk of dismissal, even though the policy was relaxed in 2016. “My major claim is to get the job back,” Guo says. “My right to work shouldn’t be deprived for having one more baby.”

“I felt like a guest”

Darry Chen is one of an untold number of “unplanned children” whose parents entrusted them to relatives or neighbors to avoid the wrath of family planning officials. The 23-year-old film student lived for years with the family of his grandfather’s sister in the southern province of Guangdong, unaware that the “aunt and uncle”—an elementary school teacher and a civil servant—who visited regularly from Shenzhen were his birth parents.

When Chen was 6 years old, his parents revealed their secret and brought him to the city. The adjustment was difficult. “I felt like a guest,” Chen recalls. “I didn’t feel comfortable speaking out. I was always afraid of doing something wrong.”

Now, as he pursues a graduate degree in documentary filmmaking from the University of the Arts London, Chen has felt a growing desire to tell his story. He has posted on a Chinese social media platform called Zhihu that hosts a group called “Secret Child” and produced a 15-minute documentary that features interviews with his biological parents and foster family. Although Chen uploaded the video to a public site, he’s restricted access to it as his parents still hold public jobs.

“Our stories should be told,” he says. “No generation before or after us will have to go through this. I’m not criticizing the policy or blaming the government, I just want to document this phenomenon of a specific era. This group should not be overlooked.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Brendan Scott at bscott66@bloomberg.net, Karen Leigh

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.

With assistance from Bloomberg