China's Rich Can Run From the Taxman, But Hiding Is Harder

China's Rich Are Finding It Harder Than Ever to Hide From Taxman

(Bloomberg) -- At home and abroad, wealthy Chinese are facing myriad new tax rules as Beijing ratchets up the pressure on tax dodgers.

State media are filled with articles trumpeting the revision of the tax code and government efforts to name and shame offenders. Familiar faces have already been caught in the clampdown. China’s highest-paid movie star, Fan Bingbing, was ordered to pay more than $100 million in back taxes and fines in October after a months-long tax probe, sending a deep chill through the domestic film industry.

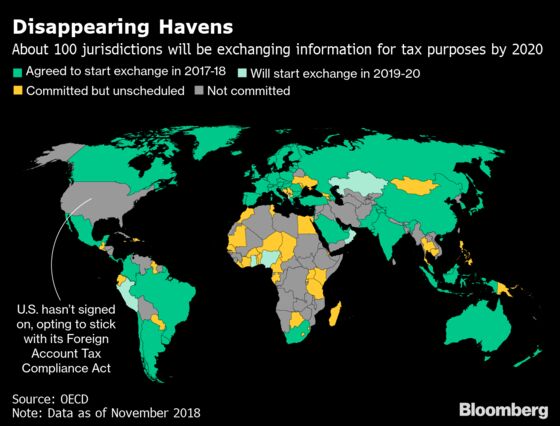

A global financial-disclosure system -- the Common Reporting Standard -- is beginning to bite for those stashing money overseas. Last year, China started automatically exchanging information alongside roughly 100 jurisdictions about accounts belonging to people subject to taxes in each member country.

The crackdown comes as wealth in the Middle Kingdom reaches new heights. A Chinese billionaire was minted every few days in 2018, according to a UBS Group AG estimate, and Boston Consulting Group said personal wealth in the nation surged to a record $24 trillion, with $1 trillion held abroad.

It means the global game of cat and mouse between the armies of accountants and asset managers working to minimize the tax payments of their clients, and the governments and regulators arrayed against them, is particularly heated in China.

“After the introduction of the CRS rules, high-net-worth individuals are pretty nervous and overwhelmed,” said Liu Shuang, a former anti-avoidance specialist for the Chinese tax bureau who now leads a wealth tax management team in Beijing and has seen demand for her advice soar since last year. “In addition to concerns about back taxes, they are also worried about the exposure of overseas assets.”

Some Exclusions

The tax authorities of CRS member countries share annual reports that detail reportable accounts, their balances and their beneficiaries. So if a Chinese tax resident opens a bank account in the U.K., British authorities will send this information to Beijing as part of their report, and vice versa. It’s a broad remit -- a reportable person under CRS is any entity or individual who’s a resident of a CRS signatory state -- although some assets such as real estate are excluded.

“Even tax havens have signed up,” said Tania Waterhouse, a tax lawyer and former director at the Australian Tax Office. “There’s just no hiding from it.”

A few holdouts remain but political, economic or social upheaval in those places makes them less favored as tax shelters. Another quirk is that the U.S. hasn’t signed on to the accord. The world’s wealthiest nation has opted to stick with its 113 separate bilateral agreements, called the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, or FATCA, which requires foreign banks to scour client lists and report anyone who could be a U.S. citizen, or face being barred from operating in the country.

Disclosure Requirements

While the wealthy of all nationalities have sought to legally circumvent CRS, some Chinese may have embraced such products with particular zeal, according to tax specialist Liu.

“Chinese people are keener to spend money to solve problems via shortcuts,” she said. “It’s this kind of mentality that has caused many people to fall into traps, not only exposing their wealth but also losing money.”

China’s State Administration of Taxation didn’t respond to a faxed request for comment.

Chinese citizens were among those who flocked to certain residence and citizenship schemes offered in places such as Cyprus and the Seychelles that could have been used to undermine CRS, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, which oversees the initiative. In October, the OECD sought to clamp down on many of these.

Plenty of strategies don’t even get that far, Liu said. “More than 99 percent of the so-called CRS-avoidance methods or products in the Chinese market aren’t very reliable,” she said, adding that many of her clients had lost money after paying for passports and products that didn’t work.

The OECD’s Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes keeps watch for anything it deems to undermine CRS. Radhanath Housden, head of the organization’s Automatic Exchange of Information Unit, said it reviewed several hundred exemptions and multiple schemes since the CRS rollout began.

“The Global Forum works continually to ensure the effective implementation of the CRS, closely monitoring all available information sources including the OECD’s avoidance disclosure facility,” said Housden, who noted the organization’s responses include engaging with tax authorities to highlight exploitative behavior by the financial sector. “Anything intended to avoid reporting must be addressed by the governments.”

Singaporean Stratagem

Bloomberg reviewed a copy of a 108-page draft document from early 2018 that seemingly outlines a Singaporean stratagem allowing Chinese persons to legally avoid CRS. Capari Asset Management, identified in the draft document as the manager of the mooted fund, says it was inadvertently prepared, outdated, never approved for marketing purposes and that the final form of the fund complies with CRS.

Still, the draft’s existence underscores the demand among Chinese clients to find ways to minimize taxes and maintain confidentiality.

Pages of flow charts and checklists lay out in Chinese and English how the fund isn’t required to report to Singapore’s tax authority or foreign governments. The package includes a sample certificate confirming the structure’s non-reporting status.

The fund may have originally contemplated designation as a non-reporting financial institution for the purposes of CRS by operating as a retirement fund, according to a tax specialist who reviewed the document, asking not to be identified because he works in the field. Bundling separate accounts together so that each made up less than 5 percent of the overall fund and fulfilling various other conditions, such as locking them up until retirement, could have seen it defined as a broad participation retirement fund, which isn’t reportable under CRS.

Last April, Singapore activated relationships with China for the automatic exchange of financial account information, likely making the approach untenable. In June, the OECD further stymied any such strategies with updated guidance clarifying that the 5 percent test should be applied at the level of the sub-fund.

Kidnappings, Extortion

Had it gone ahead, the product would have generated hefty fees. The draft stipulates a one-off establishment fee of $15,000 and annual fees of $20,000 for the vehicle, an indication of how sought-after such services are. And not just for tax reasons. A desire for privacy isn’t unreasonable, wealth advisers say. Confidential accounts may protect against kidnappings or extortion in countries where law and order is tenuous.

In any case, Capari says that the fund in its final form is registered for CRS reporting.

“These are not authorized marketing materials from Capari,” Kevin Fan, a managing director, said in an email. “None of our funds are CRS-exempt vehicles and we have every intention to meet all CRS and taxation obligations.”

A spokeswoman for PricewaterhouseCoopers, whose logo also appears on the draft document, said the accounting firm hasn’t provided CRS advice to Capari or rated any of its investment products, and isn’t involved in the marketing of Capari products. PwC’s engagement in relation to the fund is limited to providing advice for potential investors in the fund on the Australian and Chinese tax implications, she said. Amicorp Trustees (Singapore) Ltd., named as the fund’s trustee, said it didn’t author or approve the documents.

Overseas Trusts

China continues to close loopholes. In the past, rich Chinese could avoid paying taxes on overseas earnings by acquiring a foreign passport or green card, while keeping their Chinese citizenship. But this year the government has started taxing global income from all holders of “hukou” household registrations -- the most expansive way to identify Chinese nationals -- regardless of whether they are citizens elsewhere. Authorities have also introduced a new data platform, dubbed Golden Tax System Phase III, which gives them a more comprehensive picture of individuals’ finances.

China’s underground banks could now face criminal charges if they abet illegal foreign exchange transactions. Gifts of assets to relatives or third parties may be taxed while a property tax law could go into effect as soon as 2020.

Anxiety over how the new rules will be enforced has already triggered a flood of Chinese clients seeking to create overseas trusts.

Four Chinese tycoons transferred more than $17 billion into family trusts late last year with the ownership structures all involving entities in the British Virgin Islands. The moves come as China’s super rich brace for the possibility of the government going after the wealthy to push through tax cuts for the lower- and middle-classes this year.

It all means the desire to shift money abroad is higher -- and riskier -- than ever.

--With assistance from Hannah Dormido.

To contact the reporters on this story: Tom Metcalf in New York at tmetcalf7@bloomberg.net;Chanyaporn Chanjaroen in Singapore at cchanjaroen@bloomberg.net;Jinshan Hong in Hong Kong at jhong214@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Pierre Paulden at ppaulden@bloomberg.net, ;Marcus Wright at mwright115@bloomberg.net, Peter Eichenbaum, Steven Crabill

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.