China’s Latest Official GDP Report Is Accurate. No, Really

The reading aligns with independent metrics, but it’s too soon to conclude the country is done massaging its numbers.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- China’s official economic data is sparse on details, opaque in methodology, and remarkably smooth—all of which feed suspicions that it’s tweaked for political purposes. In the final quarter of 2018 it was also something else: about right.

According to China’s National Bureau of Statistics, in the last three months of 2018 the economy expanded 6.4 percent from a year earlier. That’s down from 6.5 percent in the previous quarter and the slowest pace since the nadir of the great financial crisis. But it’s not a disaster: With growth for the year as a whole at 6.6 percent, Beijing can still claim success in hitting its 6.5 percent target.

The government-issued data were in line with estimates derived from proxy gauges developed by Bloomberg Economics—possibly a coincidence. It’s certainly too soon to lay decades of suspicions about China’s economic pronouncements to rest. Premier Li Keqiang once dismissed the numbers as “man-made.” Major provinces—including Liaoning, where Li was once Communist Party secretary—have confessed to large-scale statistical fraud. The very speed with which the figures are compiled, merely three weeks to measure the performance of a $13.5 trillion economy, raises questions about their credibility.

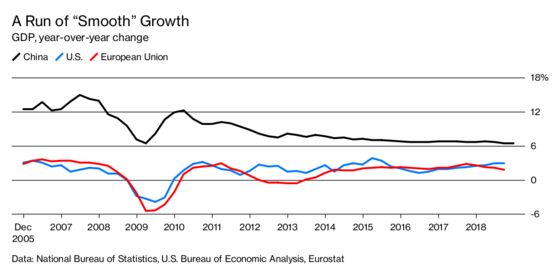

More damning still: China’s gross domestic product and other metrics scrutinized by investors are remarkably smooth, while those of other nations bounce around from quarter to quarter. On average, China’s GDP growth rate has changed 0.2 percentage points each quarter since 2011, less than half the average for the U.S.

That’s why economists trying to work out what’s really going on rely on a range of proxy gauges. Bloomberg Economics looks at three: a monthly GDP tracker based on a weighted average of activity indicators such as industrial output and retail sales; an electricity index that factors in power consumed by manufacturing, services, and agriculture, adjusted by each sector’s share of GDP; and the Li Keqiang Index, which was inspired by the premier’s suggestion that electricity, rail freight, and bank loans provide a more reliable guide to growth than official data.

These alternative barometers don’t always line up with the official GDP data. In 2015, for example, Bloomberg Economics’s numbers and those from a range of independent economists (producing China GDP proxies is something of a cottage industry), suggested growth may have fallen to 5 percent or below. For the latest quarter, though, the official and independent gauges more or less match.

To understand what’s going on, it’s necessary to take a short detour into the history of China’s economic statistics. Going back to the Mao era, the main source of distortions in the data was a conflict of interest for local officials. Provincial chiefs were in charge of reporting on the performance of their local economies, and their prospects for advancement depended on how good those numbers looked to Beijing.

In 1998, as the Asian financial crisis hammered China’s neighbors, the impact of that conflict was plain to see. Data on everything from energy consumption to air travel showed growth flatlining. Professor Thomas Rawski, an expert on China’s economy at the University of Pittsburgh, estimated that China’s economy expanded by 2.2 percent or less that year, while the official reading was 7.8 percent.

The disparity was so glaring that China’s leadership had no choice but to act. Then-Premier Zhu Rongji spoke of a “wind of embellishment and falsification” sweeping through the statistical system. In the years that followed, far-reaching reforms attempted to strip the impact of local exaggeration out of the data. The National Bureau of Statistics in Beijing took on an expanded role, and conflicted local officials were squeezed out.

Those reforms didn’t eliminate conflicts of interest at the top level. National leaders don’t have to worry about promotion. But they do set a GDP target and face a blow to their credibility if they miss it. No one has a window into the internal workings of the National Bureau of Statistics. The remarkable consistency of the data, though, raises suspicions that the top-line numbers are being massaged to conform to government targets.

A plausible, but unverifiable, alternative narrative on China’s growth over the past few years goes something like this: The slowdown in 2015 was sharper than reported. That’s what the proxy indicators suggest. It’s also consistent with the meltdown in China’s equity market and panic over a surprise devaluation of the yuan. With government policy swinging aggressively to support growth, the rebound in 2016 and early 2017 was more pronounced than official statistics show. In 2018, President Donald Trump’s trade war and President Xi Jinping’s debt-reduction drive began taking a toll and the economy began to decelerate. This time the official and proxy gauges are telling a consistent story, or at least intersecting.

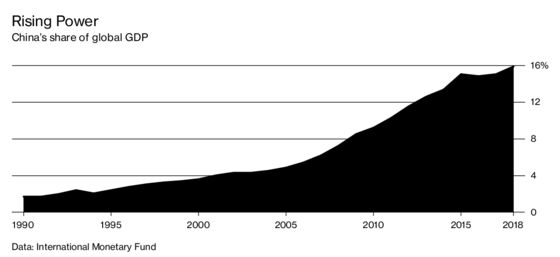

In 1998, China accounted for an inconsequential 3.3 percent of global output, and the quality of its data was of interest only to a few academics. In 2018 the country’s share of worldwide production was almost 16 percent, meaning the integrity of its statistics are a subject of interest for everyone from the U.S. Federal Reserve trying to set monetary policy to Apple Inc. forecasting iPhone sales.

Looking forward, two factors give cause for optimism. First, China’s leaders are on board: In a speech early in his six-year presidency, Xi said growth should be “genuine, with no added water”—code for exaggeration. Second, as China’s financial system opens to global investment, credible data are an essential underpinning of confidence. With incentives aligned around accurate reporting, maybe the latest GDP release will be the beginning of a trend.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Cristina Lindblad at mlindblad1@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.