Who Will Be Able to Take the Breakthrough Drug for Postpartum Depression?

Who Will Be Able to Take the Breakthrough Drug for Postpartum Depression?

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Zulresso, the world’s first-ever drug for postpartum depression, cleared a major hurdle when it won approval from the Food and Drug Administration this week. Even bigger challenges lie ahead for Sage Therepeutics Inc., the drug’s developer.

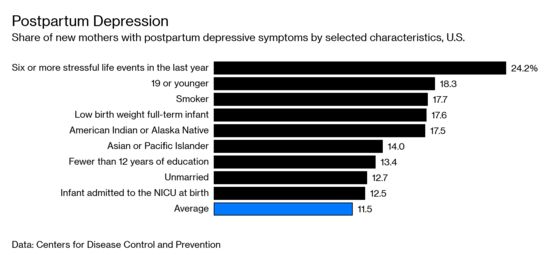

Zulresso, the brand name for brexanolone, works much faster to treat the condition than anything currently available. Experts have hailed it as “groundbreaking,” a “game changer.” And postpartum depression affects as many as one in nine new mothers. These facts alone would suggest the drug is destined to be a blockbuster. Yet there’s a difference between a drug that works and a drug that sells.

“The quality of life, with a rapid and high rate of response, is tremendous. That is the positive side,” says Kimberly Yonkers, professor of psychiatry at the Center of Wellbeing of Women and Mothers at Yale School of Medicine. But she says that there are “obvious impediments” for Zulresso. The current treatment regimen is that a patient is given a prescription for antidepressants that could take weeks to work. Zulresso is administered by a two-and-a-half-day infusion, and the company plans to charge $34,000 for it. Considering the price and logistical challenges, she says, it’s not clear how many women will ever get the drug.

Sage’s chief executive officer, Jeff Jonas, a Harvard-trained psychiatrist, says that Zulresso’s medical benefits will overcome any concerns about cost and delivery. “Every physician and every institution will make a choice,” he says. “Is it better to help someone get better in two and a half days or send them home?”

Sounds like an easy choice, but not every new mother is able to spend additional time in a hospital away from her baby. “The only moms who can really afford to take it are the ones that can basically arrange for 60-plus hours of childcare,” says Ritu Baral, a biotech analyst at Cowen Inc. “It’s not easy for probably two-thirds of people.”

Mothers such as Iris Reyes, for example. In the weeks after giving birth to her daughter Emma in March 2018, Reyes, who describes herself as a normally joyful person, found herself crying every day and feeling no connection with her little girl. Six weeks after giving birth, she returned to her job as manager of a T-Mobile store and didn’t have time to go to the doctor to address what was going on with her. She had a panic attack that almost drove her to suicide a few months later. “It was the pressure of going back to work and the pressure of being a mom and also just trying to be normal,” she says.

Reyes eventually learned that the hospital where she had given birth had a postpartum center with services for such patients. She refused to be admitted to the hospital because of the time it would take away from being with her daughter. “I just felt like it would be worse for my mental and emotional state for me to be inpatient.” She was able to receive intensive therapy for 10 weeks at a center 90 minutes from home, where she could bring her daughter.

For those who can afford a longer hospital stay, finding a bed could be challenging: Psychiatric wards are disappearing in the U.S. There were a half-million psychiatric beds in state hospitals in 1955, but fewer than 40,000 in 2016, according to the Treatment Advocacy Center. Much of that is a result of deinstitutionalization efforts that aimed to get mental health patients into community settings.

Catherine Birndorf, founder of the Payne Whitney Women’s Program at the New York-Presbyterian Hospital Weill Cornell Medical Center, has spent decades trying to improve on current treatments for post-partum depression. After raising money from friends and family, she opened the 8,000-square-foot Motherhood Center in Manhattan in March 2017; it offers intensive therapy for post-partum mood disorders and allows patients to bring their babies while they seek treatment. “We’re doing something unusual, and we want to be on the cutting edge,” she says. But the center’s landlord doesn’t allow patients to stay overnight. She sees Zulresso as an option for the most severe patients—those she would refer to a hospital, anyway. “It’s hard to come by an inpatient bed.”

The University of North Carolina Center for Women’s Mood Disorders is one of the few places set up to administer a drug such as Zulresso. It’s also where professor Samantha Meltzer-Brody ran a number of clinical trials for it. Now that the drug has been approved, Meltzer-Brody says, the medical world will start to adapt to it. “I believe that any time you have a novel treatment, the system has to catch up with where the treatment moves it,” she says.

Centers that may work include skilled nursing facilities designed to offer rehabilitation services for patients who have knee surgery, for example, if psychiatrists are able to consult with patients as they receive the drug. Meltzer-Brody works under David Rubinow, a member of Sage’s clinical advisory board, whose work helped inspire the drugmaker to test brexanolone for use in treating postpartum depression. Because suicide kills more women than any other complication in the first year after childbirth, Rubinow expects medical centers to move quickly to find a way to administer Zulresso. “If we really have at our disposal a tool that can very rapidly eliminate the symptoms and the morbidity and impairment of a severe and potentially life-threatening condition,” he says, patients will be given the drug.

Sage is running trials of another fast-acting antidepressant pill and in January, the drugmaker showed that it succeeded in reducing symptoms in a late-stage study. Because it’s a pill, that drug will be more straightforward to distribute, should it succeed in the high-stakes world of late-stage trials, where many promising psychiatry drugs flame out. In Jonas’s ideal world, both Zulresso and the follow-up pill will succeed, and then his job will be to figure out how to sell both. “I’m fine if patients have more than one option,” he says. Some women may want to be hospitalized, others may want to take the pills home with them. “For us, that’s the best of both worlds,” he says.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Eric Gelman at egelman3@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.