Inside the Dystopian, Post-Lockdown World of Wuhan

More than 80% of China’s almost 84,000 confirmed cases of Covid-19, have been in Hubei.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Every workday at Lenovo’s tablet and phone factory on the outskirts of Wuhan, arriving employees report to a supervisor for the first of at least four temperature checks. The results are fed into a data collection system designed by staff. Anyone above 37.3C (99.1F) is automatically flagged, triggering an investigation by an in-house “anti-virus task force.”

Daily routines at the facility, which reopened on March 28 after stopping for over two months because of the coronavirus pandemic that began in this central Chinese city, have been entirely reengineered to minimize the risk of infection. Before returning to the site, staff members had to be tested both for the virus and for antibodies that indicate past illness, and they had to wait for their results in isolation at a dedicated dormitory. Once cleared, they returned to work to find the capacity of meeting rooms built for six reduced to three and the formerly communal cafeteria tables partitioned off by vertical barriers covered in reminders to avoid conversation. Signs everywhere indicate when areas were last disinfected, and robots are deployed wherever possible to transport supplies, so as to reduce the number of people moving from place to place. Elevators, too, are an artifact of the Before Times; everyone now has to take the stairs, keeping their distance from others all the way.

Presiding over all these measures one Sunday in mid-April was Qi Yue, head of Wuhan operations for Beijing-based Lenovo Group Ltd. Qi, who’s 48, with closely cropped hair and a sturdy frame, had been visiting his hometown of Tianjin, in China’s north, when the government sealed off Wuhan from the rest of the country on Jan. 23. It had taken him until Feb. 9 to get home—and he was only able to make it by buying a train ticket to Changsha, farther down the line, and begging the crew to let him get off in Wuhan. His job was now to bring the factory slowly back to life while emphasizing vigilance. Compared with keeping the virus out of the plant, he said, “how much production we can deliver comes second.”

Qi is one of millions of people in Wuhan trying to figure out what economic and social life looks like after the worst pandemic in a century. In some respects they’re in a decent position. The outbreak in Hubei province peaked in mid-February, and according to official statistics there are now almost no new infections occurring (though other governments have cast doubt on China’s figures). But scientists warn that the novel coronavirus is stealthy and robust, and a resurgence is still possible until there’s a reliable vaccine. How to balance that risk against the need to reignite an industrial hub of more than 10 million people is a formidable dilemma—one governments around the world will soon be facing.

So far, Wuhan’s answer has been to create a version of normal that would appear utterly alien to people in London, Milan, or New York—at least for the moment. While daily routines have largely resumed, there remain significant restrictions on a huge range of activities, from funerals to hosting visitors at home. Bolstered by China’s powerful surveillance state, even the simplest interactions are mediated by a vast infrastructure of public and private monitoring intended to ensure that no infection goes undetected for more than a few hours.

But inasmuch as citizens can return to living as they did before January, it’s not clear, after what they’ve endured, that they really want to. Shopping malls and department stores are open again, but largely empty. The same is true of restaurants; people are ordering in instead. The subway is quiet, but autos are selling: If being stuck in traffic is annoying, at least it’s socially distanced.

Qi figures he’s probably on the right side of this economic rebalancing. Tablets are in high demand as schools around the world switch to remote learning, and companies contemplating a work-from-home future aren’t likely to skimp on technology budgets. Since restarting operations, he’s hired more than 1,000 workers, bringing the on-site total above 10,000, and production lines are running at full capacity.

He said he was painfully aware, however, of how quickly work would stop if even one employee contracted the virus. “In my meetings with my staff I always tell them, ‘No loosening up, no loosening up.’ We can’t allow any accidents.”

More than 80% of China’s almost 84,000 confirmed cases of Covid-19, and more than 95% of the roughly 4,600 confirmed deaths, have been in Hubei, of which Wuhan is the capital and largest city. Controlling the outbreak there, after a series of mistakes by President Xi Jinping’s government, which initially downplayed the risk of human-to-human transmission and failed to prevent widespread infection of medical personnel, required a herculean effort. More than 40,000 doctors and other medical staff were dispatched from other regions to reinforce existing facilities and operate field hospitals built in the space of 10 days, and car and electronics companies were pressed into making protective gear. People suspected of having the disease were required to move into dormitories and hotels repurposed as isolation facilities, and allowed to go home only after they’d been declared infection-free.

Hubei was the last region of China to resume daily life, with curbs on movement lifted progressively from late March until April 8, more than three months after the epidemic began. The government presented the moment as a decisive victory—part of a comprehensive effort to rewrite the narrative of the virus as a Communist Party triumph, in contrast to its catastrophic spread in Western democracies.

Late on the night of April 7, crowds began arriving at Wuchang station, one of three large railway hubs in Wuhan. The first outbound train in weeks, to Guangzhou, was scheduled to leave at 12:50 a.m., followed by a dense schedule of departures to many of China’s major cities. (Wuhan’s position at the junction of several major rail and road routes, along with its industrial heft, has invited frequent comparisons to Chicago.) Police in black uniforms and medical masks seemed to be everywhere. “Scan your code!” they shouted at travelers approaching the departure gates. The public-private “health code” system that China developed to manage Covid-19, hosted on the Alipay and WeChat apps but deeply linked with the government, assigns one of three viral risk statuses—red, yellow, or green—to every citizen. It’s a powerful tool with clear potential for abuse. A green QR code, which denotes a low risk of having the virus, is the general default, while coming into contact with an infected person can trigger a yellow code and a mandatory quarantine. Red is for a likely or confirmed case.

Travel between cities requires a green code, and while Zeng Xiao, 22, had hers and felt fine, she was nervous about making her train. “There’s still a chance I’ll be stopped if my temperature is too high,” she said as she neared the departure zone. Before going to the station, Zeng had checked repeatedly for a fever, worried that being even a little bit warm would prevent her from getting to Guangzhou, where she works as a teacher. “I haven’t seen my cat in almost three months,” she said. She didn’t have to worry. Her temperature scan was normal, and she was soon able to board her train south.

Another passenger leaving on the first day, Qin Xin’an, 26, had been stranded since the lockdown began. He’d been on vacation in Wuhan when Hubei was cut off, and no amount of pleading with officials could get him on a train out. By mid-February he was living off online loans. “I was eating instant noodles for every meal,” he said. He ended up getting a bed in an austere dormitory constructed by the local government for people who couldn’t leave. He also found work doing odd jobs at Leishenshan Hospital, one of the temporary infirmaries built to handle coronavirus patients. He’d lost his regular job, at a company in Jiangsu province that makes robots, because he couldn’t get back, and was now headed to Guangdong to look for another one and see his family. He hadn’t told his parents where he’d been all this time; as far as they knew, he was away working. “I will not tell them I was in Wuhan,” Qin said.

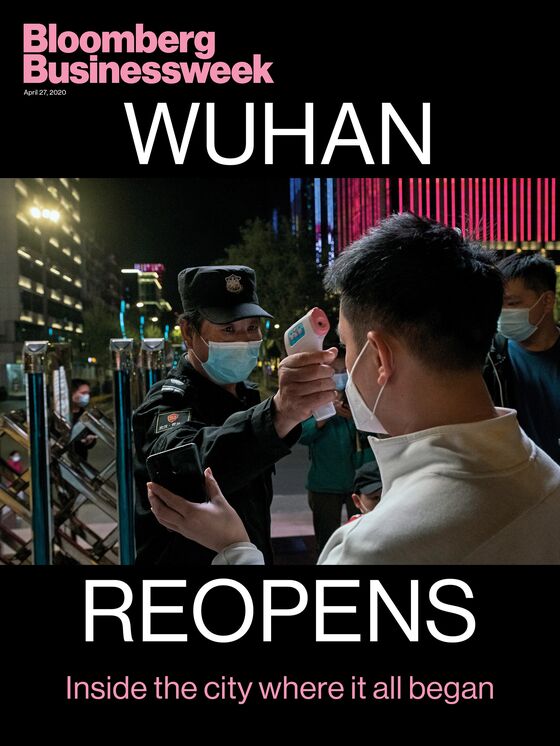

When dawn broke, Wuhan came cautiously back to life. Hairdressers were some of the first businesses to fill up. The roads were noticeably busier, and workers flowed back into office towers in the city center. But these new freedoms felt distinctly provisional. At the entrance to every mall or public building, guards stood sentry with temperature scanners, ready to turn away anyone whose reading was too high. Green codes, required even to ride the subway, have become the city’s most precious possession, and one that’s easy to lose. Merely visiting a building around the same time as a person later found to be infected can turn them yellow. And apartment compounds still reserve the right to bar residents from leaving if cases are reported there, as they did during the lockdown.

Even in the first city to confront the virus, following a containment effort as intense as any in the history of public health, the danger remains acute. “Asymptomatic cases and imported cases are still risks,” Wang Xinghuan, the president of one of the city’s major hospitals and of the Leishenshan facility, told reporters at a press conference before the latter’s closing. And many residents are still susceptible. Wang’s hospital gave antibody tests to all 3,600 of its staff, and fewer than 3% came back positive—a result that shows “there’s no herd immunity in Wuhan.” There’s only one way to durably protect the population, he said: a vaccine.

Wuhan’s businesses are nevertheless hoping for a safe but speedy return to conspicuous consumption. In the days before the city fully reopened for business, the sales team at a local Audi dealership gathered for their daily meeting. The 20 or so salespeople were all dressed in dark suits and face masks, standing well over a meter apart in neat columns. As a manager briefed them on the day’s plans, a colleague made his way through the group, spraying everyone with disinfectant as they spun around to ensure full coverage. “Customers may not be kind enough to tell you if they don’t feel well, so try not to bring them into the store,” the manager said. “Just talk to them at the entrance if possible.”

After reopening on March 23, the dealership had been selling about seven cars per day, on pace with last year despite all the restrictions. Most were relatively low-end vehicles, such as the A3, which retails for about 200,000 yuan ($28,000)—the kind of car often bought by families to complement a bigger, fancier model. “People are not willing to take public transport in Wuhan,” said the marketing director, who asked to be identified by only his surname, Pan. “And they don’t dare commute by Didi”—the ubiquitous ride-hailing app. The focus now, Pan said, was on following up with people who’d expressed interest in an Audi in the past but hadn’t bought one. They might be ready to bite. The dealership was looking to expand its current staff of about 150, and employees would soon receive the pay they’d missed during the lockdown. Another salesperson added, “It’s like a boom.”

For many other businesses in Wuhan, though, it’s anything but. Benny Xiao is director of international operations at Wuhan Boyuan Paper & Plastic Co., which produces the kinds of unremarkable but essential goods that still form the backbone of Chinese industry. In his case, they’re disposable cups, which Boyuan sells to U.S. airlines and Japanese retailers, among other clients. Xiao works from an office inside a dilapidated residential compound, and, wearing a battered gray blazer over a green button-down, he didn’t quite look the part of an international dealmaker. But he beamed with pride as he showed off a glass cabinet in his office stuffed with examples of his craft, from thin plastic vessels for economy-class soda to a sturdy tumbler he’d tried, unsuccessfully, to sell to Starbucks Corp.

The first months of the pandemic were challenging for Xiao, as they were for everyone in Wuhan. His wife, now retired, spent her career as a doctor at Xiehe Hospital, one of the first to report cases of what was later identified as the coronavirus, and she’d begun hearing from colleagues in mid-January about the impending crisis. Sick residents “were lining up outside Xiehe at 10 p.m. in the freezing cold,” many of them “older people who could barely make it,” Xiao recalled. “Patients were really desperately looking for help.” He and his wife had stocked up on food before the lockdown began, but three weeks in they started to run out. Unlike in Europe and the U.S., Wuhan’s containment measures made it difficult for people to leave their buildings, even to buy groceries, forcing them to rely on delivery apps, government drop-offs, and neighbors who wrangled permission to go out. At one point, Xiao had to spend 26 yuan (almost $4) for a single cabbage, more than triple the usual price. Some of the vegetables provided by local officials were barely edible.

He returned in late March to a company in severe trouble. Orders in the first half of the year were headed for a 50% drop, with demand from food deliveries failing to offset the calamitous decline in air travel. The government had made some financial help available, but Xiao wasn’t sure he’d be able to avoid layoffs. “Back in January and February, I was expecting things to come back to normal in April,” he said. Instead, “I was just calling the bank this morning to tell them that I can’t repay the interest on our loan.”

For a country that’s experienced an essentially uninterrupted boom throughout the living memory of anyone younger than 50, broad-based economic pain is deeply unfamiliar. The Chinese economy shrank 6.8% in the first quarter of the year, and the International Monetary Fund estimates it will grow just 1.2% in 2020, the worst performance since 1976. Urban unemployment, a widely scrutinized indicator of overall joblessness, rose to a record 6.2% in February before pulling back slightly in March. And it’s not clear what China’s business model will look like in a world where Europe, the U.S., and other key markets for its goods are flirting with a depression.

Xiao is 64, part of a Chinese generation that had seen more than its share of history even before the coronavirus emerged. But he struggled to recall anything in his experience that was more dramatic, save perhaps the famine of the Great Leap Forward, when he was a young child. “This is the biggest crisis of my lifetime,” he said.

The entrance to Wuhan’s Biandanshan Cemetery is marked by an impressive stone gate with a pagoda-style roof and a frieze of a ferocious-looking dragon. But in recent weeks, it’s been partly hidden behind a series of bright yellow crowd control barriers surrounded by temporary metal fencing and watched carefully by police. Almost no one is permitted to enter until April 30, and even then access is likely to be strictly controlled.

Officially, no patients in Wuhan are still dying from Covid-19, but the treatment of those who did pass away remains an extremely sensitive subject. On Tomb-Sweeping Day in early April, when Chinese families traditionally gather to pay respects to their ancestors, Wuhan’s cemeteries were kept closed. Funerals have been banned until at least the end of the month, and family members of the dead have reported pressure from government officials to mourn quickly and quietly. According to the government, these measures are purely a matter of public health, because family gatherings are a potential vector for infection. But the restrictions also help Beijing avoid having funerals become a venue for people to vent anger about how the epidemic was handled, or to ask uncomfortable questions about subjects such as China’s true death toll.

Whatever the reasons for maintaining the ban, some mental health providers in Wuhan have expressed fears that the inability to properly mourn loved ones will have deep and enduring psychological consequences. The city’s residents were the first to undergo the unprecedented social shutdown that’s been repeated around the world, and it seems certain to mark many of them for a long time, especially if it’s compounded by a prolonged economic slump.

Yao Jun is among those struggling to move on. The petite 50-year-old is the founder and general manager of Wuhan Welhel Photoelectric Co., a manufacturer of welding helmets and protective masks that exports to France, Germany, and the U.S. She came back to work on March 13 after wading through approvals from four layers of government, including her local neighborhood committee, which took 15 days to assess Welhel’s ability to prevent infections. “We can’t afford to have a single one,” Yao said in an interview at her factory. Every day the production line can run is crucial: Welhel was trying to catch up on orders it hadn’t been able to complete in the first few months of the year, even as Yao wasn’t sure her customers in locked-down overseas markets would be able to take the deliveries. She had no idea when more business would come in, given what’s happening to the global economy.

Despite the uncertainties, she was trying to focus on work rather than what the city had just gone through. “I can’t see news about medical workers without crying,” Yao said, choking back tears and rubbing a jade keychain attached to her phone. She was having trouble sleeping, as she turned over the stories of doctors and nurses who’d succumbed to Covid-19 again and again in her head: “I don’t know these people, but if someone tells me what happened to them, it’s devastating. These deaths aren’t just numbers or strange names to me. They’re vivid lives.” She believed that many of her neighbors and colleagues were experiencing similar emotions but might not be willing or able to talk about them. “Many other people are traumatized but can’t recognize the problem or express their feelings,” she said.

The pandemic was causing Yao to rethink her life. She spent almost half of last year on the road, often visiting clients overseas. Now, she said, she wanted to spend much more time at home, keeping her family close. Her son was supposed to return to Australia for university in February, but he was unable to get there, for obvious reasons. Yao didn’t want him to go back.

Even after seemingly world-shattering events, human behavior has a way of reverting to the mean. In the weeks after Sept. 11, commentators predicted the end of globalization, of the skyscraper, of irony—which all, needless to say, persisted. Within a couple of years of the global financial crisis, banks and homebuyers were back to arranging risky mortgages, and the very wealthy were back to, and then well beyond, pre-2008 levels of excess.

It’s reasonable to think this time will be different. Hardly anyone alive today has endured a pandemic this severe, and the basic problem it’s created—that anyone, whether friend, family, or stranger, might be a vector for lethal infection—is uniquely corrosive to the daily interactions that keep countries and economies going. An effective vaccine could be at least a year off, and given what the world has learned about how quickly a novel pathogen can shut everything down, even that might not return things to the way they were. Wuhan was the first place to traverse both sides of the Covid-19 curve, and how it changes, or doesn’t, in the disease’s aftermath will say a lot to the rest of us.

Many of the city’s methods won’t be universally applicable. Few other governments could assemble the all-seeing anti-viral surveillance China is trying to put in place, even if they wanted to. Fewer still, probably, have populations that would tolerate it. But whatever the tactics, the key lesson of Wuhan could be that the price of beating the virus is never-ending vigilance and a reordering of priorities that will be hard for many to accept.

At a Starbucks in one of Wuhan’s fancier shopping districts, Ma Renren, a 32-year-old entrepreneur who runs a small marketing agency, talked about how he was sorting out these questions for himself. The store was open but only serving drinks to go, with customers permitted to sit at outdoor tables. Security guards were keeping a close eye on things, interrupting conversations to tell patrons to keep their masks on between sips and not sit too close together. Ma, who was wearing fashionably oversize glasses, a black baseball cap, and—of course—a light blue medical mask, had gone to stay at his parents’ apartment on Jan. 24, intending to help take care of them. But soon he began to suspect that he might be sick. It was a time of greatly heightened emotion: No one knew the true fatality rate, and people in Wuhan were seeing reports on social media of appalling conditions in overwhelmed hospitals. “I wrote my last words one night and decided to say farewell to my parents and go to the hospital alone the next morning,” Ma recalled. “I knew that if I went, I couldn’t necessarily expect to come back.”

He changed his mind at the last minute and eventually felt better, though the psychological effects lingered. He began having panic attacks, his breath short and his heart pounding. After looking up the symptoms online, he concluded that he was experiencing post-traumatic stress. Experiences like his, Ma thought, would make many people more introspective and more focused on those closest to them. “We will put aside more time for ourselves and our families” and for the other relationships that seemed truly worth holding on to during the crisis, he said. “Misfortune tests the sincerity of friendship.”

Ma was now trying to get his company back on its feet. The government had recently sent him a tax rebate as part of its stimulus measures, but this would help only so much. Tourism has collapsed, and few potential clients have much money for promotion. “There’s nothing to do but move on,” he said. Ma had, inevitably, lowered his ambitions, and for the time being he was all right with that. “We worked nonstop for years, chasing every opportunity,” he said. Now, “everyone I know has one goal for 2020. It’s to survive.” —With assistance from Gao Yuan, Haze Fan, and Jinshan Hong

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.