The Work-From-Home Boom Is Here to Stay. Get Ready for Pay Cuts

Getting used to the ‘new normal?’

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Rachel Musiker was on maternity leave, stuck in a two-bedroom basement apartment with a newborn, when Covid-19 started spreading in New York City. Her husband, who works in the insurance industry, was still commuting on the subway, so she started making him shower before holding the baby. “It was just starting to feel unsafe to even go for walks,” Musiker says. So, on March 14, they packed a few bags and drove to Rochester, N.Y.

Musiker had loved her Brooklyn neighborhood. The rent was ridiculous, but there was a bistro a few steps from her apartment that served a fabulous brunch (if you were willing to wait for a table) and a day care a half-block away where she planned to send the baby. None of that mattered now. The day care might not even be open when she went back to work; brunch was a Before Times indulgence.

She and her husband had planned to stay with her parents for two weeks in Rochester. They ended up there for nine. Afterward they rented a house outside town on Lake Ontario, and Musiker settled back into her job as director of communications at the real estate and technology company Redfin Corp. In August the couple bought a four-bedroom, 3,400-square-foot house for $355,000.

There was a time when the thought of relocating to her hometown would have been something close to a nightmare for Musiker. But, to her pleasant surprise, Rochester wasn’t that bad. Her mom was helping with child care, it was easier to shop for groceries in a car, and there was a straight-out-of-Brooklyn craft brewery nearby. “It was a whole bunch of young people in a field at picnic tables drinking in the middle of the day,” she says. “We could picture it in Williamsburg.”

Like many people during the pandemic who could suddenly work remotely, Musiker had moved without figuring out all the details with her employer. One thing they hadn’t discussed was salary. Now that she lived in an inexpensive city, Redfin asked, would she be willing to accept a pay cut?

It’s a question that’s been foisted on many white-collar employees. In February only 8% of the U.S. workforce did their job entirely from home, according to research from the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. It spiked to 35% in May, as offices stayed closed and workers fled to less densely populated areas. The work-from-home rate has fallen a bit since and will drop further as vaccines are distributed. But a substantial number of workers are likely never going back to their old offices.

This shift has been especially pronounced in the tech industry, which has a high concentration of employees who can work from anywhere but are based (for now) in expensive coastal cities. Facebook, Microsoft, and Stripe have announced that more employees will be able to work remotely indefinitely. Like Redfin, those companies are also adjusting pay for workers who relocate. Musiker’s salary and bonus will go down about 20% next year if she stays in Rochester. She’s resigned to the trade-off, at least for now. “So much in the world is not how I thought it would be,” she says.

What Musiker and workers like her do in the long run could be one of the lasting legacies of the pandemic. If the exodus to second cities and exurbs becomes permanent, it has the potential to improve corporate balance sheets, remake labor markets, and profoundly reshape the American landscape. Millions of upwardly mobile urban dwellers may find that they can move out without sacrificing their career ambitions. “It’s only just started,” says Nick Bloom, an economics professor at Stanford who has studied work-from-home trends. “There’s going to be a reverse of the urban boom.”

There are doubters, of course. Jamie Dimon, Larry Fink, and Reed Hastings—the bosses of JPMorgan Chase, BlackRock, and Netflix, respectively—have all argued against the shift, suggesting, in various ways, that remote employees aren’t as productive, that corporate cultures will be eroded, and that workers’ mental health could suffer.

Musiker’s boss, Glenn Kelman, shares some of those concerns. The Redfin chief executive officer loves his company’s Seattle headquarters, which features catered meals and a video game room, but he now wonders if he was imposing his preferences on his employees. “There’s a narcissism to it,” he says, “that, if somehow they’re in close proximity to me, we will share some kind of weird energy.”

That’s part of why he set a new corporate policy in August allowing what Redfin calls “headquarters employees”—the 1,000 or so people who aren’t real estate agents or field operations staff—to work remotely full time as long as they accept “localized” compensation.

The policy makes sense for Redfin, which has more to gain than most employers from a wholesale labor shift. The company, which has been around since 2006, is a low-cost real estate brokerage that also maintains a popular home-shopping app. It employs about 1,900 salaried agents in more than 90 markets in the U.S. and Canada and offers listing fees that can amount to as little as a third of the industry standard.

When the virus shut down the economy this spring, investors worried Redfin would be saddled with big losses. The company had expanded into mortgage lending and had been buying homes for cash and flipping them—business practices that had begun to look dicey. Home sales plunged, hurting agent fees. Redfin’s stock lost two-thirds of its value from Feb. 21 to March 18, falling to $10.33 a share. By early April, Kelman had decided to forgo the remainder of his $300,000 base salary for the year and temporarily cut the pay by 10% for all headquarters staff who made more than $80,000 a year. He furloughed or let go two-fifths of the agents and their support staff.

Then, almost as quickly as things had fallen apart, they came roaring back. Low mortgage rates and newfound work flexibility gave people a reason to buy homes in places they would never have considered before. In August the National Association of Realtors reported that the area around Kingston, N.Y., a working-class town about two hours north of Manhattan, had the fastest-appreciating home prices in the U.S. Throughout the West, communities near national parks and ski resorts were becoming “Zoom towns” for remote workers, dramatically pushing up home prices.

Millennials, who’d spent a decade horrifying their parents by paying $3,000 a month to occupy tiny, roach-ridden warrens near farm-to-table restaurants in big cities, had already started seeking out farm-to-table restaurants in the suburbs. The pandemic accelerated that trend, too.

Redfin took advantage of all this, allowing homebuyers to video chat with agents or to take virtual-reality tours on its website. Revenue ended the second quarter at $214 million, up 8% from a year earlier. The company reinstated salaries for headquarters staff in June and by the next month had brought back the agents it furloughed. In September the stock climbed to more than $50 a share.

Inside the company, though, employees had been demanding answers. “We had people asking, ‘Well, when are we going to come back?’ ” Kelman recalls. “Some of them wanted to know if they could move to Montana.” The head of product design, Colin Grigson, 38, had been spending part of his time in an Airstream on land he owned outside Walla Walla, Wash. There was no running water, but he was logging on to video calls through a Verizon hotspot and using solar panels to power his computer. “I’d be in these meetings, and they’re like, ‘How is this working?’ ” Grigson says.

More common, though, were questions about regional moves. An employee wanted to leave Seattle’s Queen Anne neighborhood for Mill Creek, Wash., about 25 miles north. How often would she have to come into Redfin’s headquarters? Even Kelman’s executive assistant was thinking about moving to a far-flung suburb.

In June, Redfin told employees they wouldn’t be required to come back to the office for the rest of the year, and Kelman started working with his executive team on a longer-term plan. Many companies and large organizations, including the federal government, pay differently in different places, because the costs of living and labor can vary widely. Redfin had been no exception, and it already had a process for changing pay for agents when they moved between markets. But, until that point, relocations and salary adjustments for headquarters staff had been handled on a case-by-case basis.

Over the summer, Redfin’s human resources team began surveying employees and researching how businesses such as Facebook, Uber, Amazon, and Mastercard were approaching the challenge. Even in normal times, getting the numbers right is tricky. Pay too little, and a business will struggle to recruit. Pay too much, and profits suffer. So companies constantly keep tabs on the cost of labor in markets where they operate. Before the pandemic, Redfin considered raising engineer salaries every six months to stay competitive with the big tech companies. Remote work introduced a whole new set of challenges, Kelman says. It was like “opening an office in every American city” all at once.

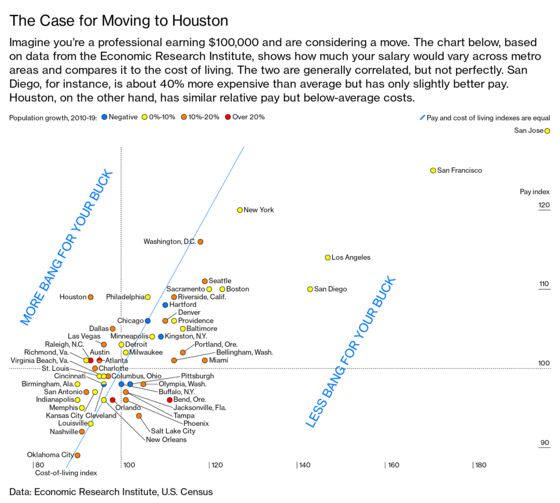

Suzanne Sanders, director of compensation, started her analysis by getting data on roughly 7,500 cities from the Economic Research Institute, which compiles information on wages and the cost of living across the U.S. She grouped the data by the state and metro area and focused on professionals who made around $100,000 a year, roughly the midpoint for Redfin’s Seattle headquarters staff. She also included variations for different kinds of jobs, such as software engineer and product manager, creating an “insane spreadsheet.”

By late August, Redfin executives had settled on an approach that divided metro areas into tiers based on cost. There were still lots of judgment calls to be made. Should Portland, Ore., where the median home sold for about $450,000, be lumped in with Seattle, where it fetched $640,000? Was it right to separate the huge sprawl east of Los Angeles County, which is part of the Riverside metro area, from Los Angeles itself? People sometimes commute between the two, but the cost of living is about 25% lower in Riverside.

Then there was Bend, Ore., a sun-soaked city on the eastern side of the Cascades that’s popular with outdoorsy types and thus a bit more expensive than comparable locations. On Aug. 24 the executives went back and forth during their weekly Google Hangout, debating where to put the town—or whether to call it out at all.

“Have you been to Bend? It’s so small,” said one executive, suggesting they could safely ignore it.

Kelman disputed this. “It’s growing incredibly fast,” he argued. “It’s like the Austin of Oregon.”

Two days later, Kelman sent an email to all staff outlining the new policy. He said he expected most headquarters employees to eventually come back to a Redfin office at least a few days a week, but they’d now have the option to work wherever they wanted full time if they got approval from their manager and a senior executive. Employees would also get six weeks of notice before offices reopened.

Then he turned to the juicy stuff: money. Extremely expensive areas (the San Francisco and San Jose metro areas) would continue to command the highest salaries and equity awards. Recruiting and retaining people in two of the most costly housing markets in the country would be impossible without paying top dollar. Expensive areas such as Boston, Los Angeles, New York, Portland, and Washington, D.C., as well as their suburbs, would hew to the same levels Redfin had been paying employees in Seattle.

After that, there was a big group of mid-tier areas. Anyone who moved from an expensive place to one of these would get a 10% to 15% reduction in cash compensation (salary, plus bonus), as well as 10% to 20% less in stock. These included Austin, Baltimore, Chicago, Denver, Houston, Miami, and Philadelphia, as well as Frisco, Texas, just outside Dallas, where Redfin has an office. The company also threw in a few cities in the Pacific Northwest, including Olympia and Bellingham in Washington, and Bend.

Everything that didn’t get called out—which included vacation spots such as Aspen, Colo., Rust Belt towns like Detroit and Rochester, and some major metro areas like Atlanta—ended up in a vast (and vaguely insulting) bucket called “Rest of the U.S.” Employees who moved to these places would expect a 20% reduction in cash compensation and a 25% cut to equity awards, even though a few of these locales were bound to have higher costs than Seattle.

Almost a hundred questions poured in during a live employee Q&A in late September. Workers wanted definitions of the costs of living and labor and to know how their specific circumstances would be treated. A few asked the obvious question: Why was it fair for people doing the same jobs to be paid different wages depending on where they lived? Kelman had anticipated the pushback. “Even for a business where everyone is in one office, pay is a hornet’s nest,” he wrote at the end of his email outlining the policy. “What makes pay especially tricky now is that simplicity and fairness trade off with one another.”

Most employees chose to see the bright side. Nick Smith, a 35-year-old senior product manager in Seattle and avid snowboarder who’d been with the company for two and a half years, was already headed to Bend when the policy was announced. The 10% to 15% pay cut seemed fair to him, because his research suggested wages in Bend were as much as 22% less than what they were in Seattle. (A senior product manager at Redfin in Seattle can make between $147,000 and $163,000 in salary, before bonuses and equity.) “It was a sigh of relief,” Smith says. “I was like, ‘Yes!’ ”

He and his wife sold their four-bedroom Craftsman-style home in a walkable Seattle neighborhood and, for roughly the same money, bought a rural property that felt like a palace. Their new house is 4,800 square feet and has an in-law unit, on about 3 acres outside Bend and 32 miles from the closest ski mountain. Redfin’s remote-work policy—and what Smith was reading about other companies—made him comfortable that he wasn’t committing career suicide. He says he plans to stay in Bend for the rest of his life and raise his two kids there. “I don’t want my options to ever be limited,” he says. “And I don’t think they will be.”

At least for a narrow slice of the workforce, this seems to be the case. The remote positions U.S. employers most want to fill right now are dominated by tech roles, including front-end developer, full-stack engineer, and product manager, according to LinkedIn. For these jobs the pandemic has created what amounts to a national labor market that could ultimately cause salaries to stagnate in tech hubs while they gradually rise elsewhere. If companies can source talent anywhere more cheaply, the extremely high salaries in the Bay Area and Seattle may look a lot less reasonable.

Kelman has been attuned to this for years. Redfin used to pay engineers fresh out of school about $80,000 a year, but that had spiked to around $120,000 to $130,000 as the company has tried to keep pace. “Part of what we’ve always been doing is rationalizing the higher pay,” he says. “Our CFO’s perspective on this isn’t ‘Why are we lowering pay in Dallas?’ It’s ‘Tell me why the worker in San Francisco, earning 50% more than the worker in Seattle, is that much more productive.’ ”

Much wider adoption of remote work has implications beyond money. Many companies say remote work will help recruit more diverse employees. Redfin has been somewhat of a leader on this front, hosting a symposium on real estate and race two years ago and publishing data regularly on diversity in its workforce. Even so, only 3% of its technology employees are Black. As Kelman points out, “one reason engineering has been this enclave of White privilege is because we created a cult around a certain type of person.”

Consider Phyllis Njoroge, who grew up in Massachusetts. After graduating from Tufts University in 2019 with a degree in cognitive and brain science, she started making spreadsheets of places in the U.S. that had a warm climate, were diverse, and had a reasonable cost of living. Houston won out, and she moved there in March to start looking for jobs. She initially found work as a hostess at a restaurant, only to have it close after her first day because of the virus. Meeting people in a city where she knew no one proved challenging with so much shut down.

Then, in June, one of her former college classmates contacted her on LinkedIn, saying Redfin was hiring product managers. Njoroge, who is Black, initially hesitated, because she didn’t want to move to San Francisco. She’d never visited, but its extreme wealth inequality and widespread homelessness were a turnoff. A friend had also told her that he’d become “hyperaware” of how few other Black people were in the city. Over the summer, though, Njoroge realized she could work from Houston, at least until the end of the year.

Her job even came with a Bay Area salary despite her living with roommates in a city where the costs are about 45% lower. As much as she feels productive working remotely, there are drawbacks. “It’s been a hard adjustment to learn how to make casual conversation” with co-workers, she says. Njoroge plans to eventually move to the Bay Area once Redfin’s offices reopen, though it’s unclear when that will be.

Her situation hints at the potential complexities to come for Redfin and its employees. A senior product manager may be able to acquire acreage in Bend and do his job remotely in a way that a more junior staffer from Houston, with no built-in network, can’t. Another big question is how to treat workers who want to come back to the office for only a few days a week. For now, Redfin isn’t making a distinction between those who come in every day and those who sometimes work from home, which means Grigson, the Airstream guy, will still be able to collect his Seattle paycheck, even if he occasionally logs in from Walla Walla while he builds a house out there. Not that anybody is coming back soon. In October, amid yet another wave of Covid infections, Kelman announced that Redfin won’t expect people in its offices at least until June 1. He also said those who moved only temporarily during the pandemic wouldn’t have their pay changed.

In general, Kelman says, he wouldn’t be surprised if salaries eventually inch up in smaller cities as more companies allow for remote work. And the promised cost savings on real estate might not be as great as some expect. The overall need for office space could drop about 10% to 15% in the U.S., according to the research firm Green Street, but that could be offset if companies spread employees out more to make them feel more comfortable. As Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg conceded in a livestream with employees in May, “it’s really unknown what the economics of this are going to look like.”

The uncertainty goes well beyond real estate and business. Where people live will have profound implications on everything, including politics and climate change. An exodus from California could make the state more competitive for Republicans and turn Texas more toward Democrats. But it’s also possible that people who leave will select regions where they feel more among their political tribe, deepening divides. Telework could significantly decrease carbon emissions, but it could also lead to dirtier commuting patterns if more people end up driving in from exurbs a few times a week, rather than riding public transit or walking from an apartment near the office.

What this means for cities is going to be complicated, too. Younger workers will probably still come to urban areas to start their careers and have fun. “For highly educated people, cities are marriage markets,” says Jenny Schuetz, a fellow at the Brookings Institution who studies housing policy. Married strivers may also stick around to be close to the action, or if both partners can’t find fulfilling work in the Zoom town of their dreams. But lots of other people are going to decide they can get more of what they want in cheaper cities or suburbs, whether that’s access to nature, a home with a yard, or good schools, even if the dating scene leaves something to be desired.

This potential shift could have devastating consequences for extremely expensive places, but it could also spread wealth more evenly. Before the pandemic, “America had become less mobile than almost at any point in our history,” Kelman says. “No matter what the economic cost of being in San Francisco, people would pay it.” Having more remote workers means “wages in Texas are going up,” he says. So are housing prices. “You can’t have a $2 million, 2,000-square-foot house in San Francisco and a $200,000 house in Dallas that are basically the same for very long when there are airplanes and internet connections and Zoom.”

None of this makes the decisions employees have to make over the next several months any easier, especially for those who relocated in a hurry. Musiker, the Redfin communications director, has until May to figure out whether she’s staying in Rochester permanently and taking the pay cut. She’s still not sure—and the decision will depend partly on whether her husband is allowed to work remotely after the pandemic—but she’s more open to living upstate than she ever thought she’d be. “We were making a lot of sacrifices in Brooklyn,” Musiker says. In Rochester, “we get so much more for our money.”

Read next: U.S. Economy Could Get a Boost From Expanded Child Care

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.