While Washington Dithers, States Put Infrastructure Spending on Ice

While Washington Dithers, States Put Infrastructure Spending on Ice

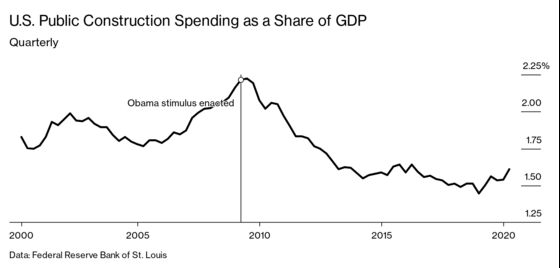

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- For years, U.S. infrastructure has been waiting for a blast of new money. Instead, the coronavirus slump is draining away the already limited resources available to maintain and improve it.

Just three months ago, when the country went into lockdown to curtail the spread of Covid-19, there were expectations the crisis would spur the government and lawmakers in Washington into long-delayed action. The Trump administration is preparing to unveil a $1 trillion infrastructure proposal as part of its push to revive the U.S. economy, according to people familiar with the discussions, while Democrats today presented their own $1.5 trillion plan. Yet experts say that even if a bipartisan deal could be struck, any increase in federal funding for highways, bridges, and the like may not be enough to compensate for reductions in infrastructure spending at the state and municipal levels, preventing many projects from moving forward.

Tara Beauchamp, a project manager at Anderson Columbia Co., a family-owned contracting company in Lake City, Fla., has already seen at least one project canceled because states have been tightening their spending. She’s worried that more will do so as the shutdowns and the recession eat into revenue streams that pay for transportation and other types of projects. Road traffic in the U.S. is down 38%, which is crimping revenue from excise taxes on gasoline and highway tolls.

“You don’t know when they’ll start trying to reserve money by being more cautious,” Beauchamp says about the states. “We’re going to senators and governors, preparing to tell them we need to keep the budget up for the state because a lot of people are affected. If we don’t have road work, Caterpillar is not selling to contractors. From paint subcontractors to concrete manufacturers to men who lay sod, it trickles down to so many people.” About 1 of every 10 jobs in America is related to infrastructure, according to the Brookings Institution.

Barbara Smith, chief executive officer of steelmaker Commercial Metals Co., based in Irving, Texas, told analysts in a March earnings call that she expected rapid moves toward an infrastructure bill. Some three months later, she and the rest of the industry are still waiting. In a May 19 interview, Smith said she worried about a slowdown in her business next year as states scramble to get a grip on how rising medical costs and other expenses related to the pandemic, as well as falling tax revenue, will impact them. On a June 18 earnings call she said she hasn’t abandoned hope that Republicans and Democrats could arrive at a compromise, given that both parties are eager to create jobs. “I think there will be something that both sides can agree on,” said Smith, noting that a deal in Washington could boost demand for steel by as much as 1.5 million tons.

Donald Trump has periodically called for more spending on infrastructure, including during his 2016 presidential campaign. On March 31 he tweeted that with interest rates back near zero, it would be a good time for a $2 trillion infrastructure bill. That echoed his call two years ago for Congress to dedicate $1.5 trillion for infrastructure investment. That plan required states to put up at least 80% of the total costs of projects.

But hopes for federal legislation ended in May 2019 after Democrats said the president vowed not to work with them unless they stopped investigating him and his administration.

After the pandemic hit, both parties appeared to converge around the idea of a public works-centered stimulus inspired by Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. But momentum dissipated following disagreements on how to fund it. (In case you’re wondering, spending on Depression-era infrastructure programs totaled about $207 billion in present-day dollars.)

The inability of politicians in Washington to find common ground is forcing bureaucrats at the state level to scramble for alternatives. The American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials estimates an average loss of at least 30% of state transportation revenues in the next 18 months if lockdowns continue and people remain in their homes. The association is asking Congress to greenlight about $50 billion in flexible federal spending to offset those losses.

States are required to match about 20¢ of every dollar they get from the federal government to build highways and bridges. If a state fails to make the match, Washington cancels the funding. That can be devastating for states such as Montana, which gets as much as 90% of its infrastructure budget from the federal government.

Beauchamp says Anderson Columbia mostly does highway and bridge work in Florida and Texas, two states where infrastructure funding is in good shape. But the company has already seen the cancellation of a tender for a $709 million project in North Carolina to widen Interstate 95 near Raleigh. It’s on a 20-page list of delayed projects that appears on the website of the state’s department of transportation. North Carolina, along with Texas and Florida, is among a group of states seeing a sharp uptick in new coronavirus infections, which is forcing authorities to divert monies to help fund the public health crisis.

Most infrastructure projects are prefunded, meaning companies aren’t all that worried about 2020. But Beauchamp and others are already fretting about 2021 projects that might not receive financing if states remain partially closed. The real test may come in a matter of weeks, when states finalize spending plans for the fiscal year that begins July 1.

“When you have to shut down restaurants and small business, the impact is very sudden and severe,” says Joseph Kane, a senior research associate at Brookings. “But when it comes to infrastructure projects, those budgets are determined a long time before. So right now we’re sort of at the tip of the iceberg in terms of these impacts.”

Also looming in September is the expiration of the FAST Act, a program last reauthorized under the Obama administration in 2015 giving $305 billion in funding over five years for surface transportation infrastructure planning and investment. Lawmakers face a choice of either extending it or coming up with a long-term replacement.

The plan Democrats unveiled today goes far beyond roads and bridges. It encompasses roughly $500 billion in highway and transit funds, $100 billion for schools, $100 billion for affordable housing, $100 billion for broadband, $65 billion for water projects, $70 billion for the electric grid, $30 billion for hospitals and $25 billion for the Postal Service over 10 years.

It’s not yet clear how closely the plan the Trump administration is putting together will align with the Democrats’ proposal. “The bottom line is the state DOTs need a backstop,” says Jay Hansen, executive vice president of advocacy for the National Asphalt Pavement Association. “All of them need Congress to do their job and pass a multiyear reauthorization bill with increased funding for investing in highways, roads, and bridges.”

Smith, of Commercial Metals, said in the May interview that while her order book remains strong, her worry is that if state budgets run short and the FAST Act isn’t renewed, the steel producer will see cancellations heading into next year. And that’s the thing about the pandemic: The worry isn’t just about a loss of economic activity now, but about the lingering effects of the virus months and potentially years down the line. “We have an economic shock that translates to an economic slowdown,” she said. “But the FAST Act and making up some of the budget shortfalls could go a long way and be very helpful.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.