With the 737 Max Grounded, Airbus Can’t Build Planes Fast Enough

With the 737 Max Grounded, Airbus Can’t Build Planes Fast Enough

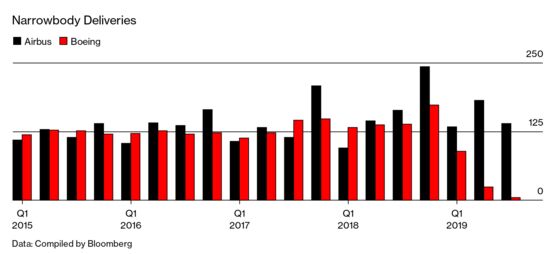

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- For decades, Airbus SE and Boeing Co. have been fighting each other for orders. In 2017 and 2018, Boeing delivered more aircraft, but after two fatal crashes in five months, its 737 Max was grounded last year, and it was forced to halt production and deliveries of the popular jet. With its rival in crisis, Airbus supplied 483 more planes than Boeing in 2019, the biggest margin in their 45-year battle. Airbus secured more than 700 net orders for narrowbody aircraft, while Boeing lost more deals than it won, ending the year down 51 narrowbody orders.

While the company has been careful not to revel in Boeing’s misfortunes, they give Airbus the opportunity to reshape the narrowbody market for years. Industry consultant Mark Martin estimates that Airbus could one day deliver 60% to 65% of single-aisle planes (up from about 50% now), which are the most widely used type of aircraft and bring in the bulk of profits for both companies. “It has opened the door for Airbus to fill up the huge hole that the Max grounding has created,” Martin says.

Buying a plane, however, isn’t like buying a smartphone or a car. Airbus and Boeing are in a duopoly, meaning alternatives are limited. Waiting lists for the most popular aircraft stretch out for years, so pulling out of a Max order means joining the end of a long Airbus line. Purchase agreements include upfront payments that would be lost in a cancellation, even during production delays, and airlines like to build fleets around one maker to streamline crew training and maintenance.

Airbus’s main competitor to the Max is the A320neo, and the company is delivering the plane in greater numbers and types. It’s introduced variants of the larger A321 model that can fly overseas routes that were previously the domain of less fuel-efficient widebodies. Airbus is also considering an attack on the Max by stretching its smaller A220, which seats 100 to 150 passengers and uses lighter materials and more advanced aeronautics. (Bombardier Inc. designed the plane, but cost overruns forced it to find a partner. On Feb. 13, the company announced it was exiting the program entirely.) Airbus Chief Executive Guillaume Faury says a stretched version of the A220 is something the company considers in the future. Such a move would bring seating capacity closer to that of the A320 and 737, which fit about 180 passengers on average. Southwest Airlines Co., which flies only 737 models, is “looking at” the A220 as an option, Chief Executive Officer Gary Kelly says. Air France, which has ordered 60 A220s, has said it would be interested in more purchases of a larger version.

But Airbus’s biggest challenge is less about winning orders than about finding space and parts to build more planes. The company had to trim its 2019 delivery target as it struggled to fulfill customized cabin layouts for the A321. Its global production lines for A320-series planes are working on an eight-year backlog of orders at current build rates, with no new delivery slots free until 2024. That’s an obstacle for airlines such as European discount giant Ryanair Holdings Plc, one of Boeing’s biggest customers. It’s said it would discuss an order with Airbus, but the wait times are a nonstarter.

Airbus makes about 60 A320 planes a month and has announced that it will increase production to as many as 67 a month by 2023. The European planemaker said Thursday that it expects to hand over about 880 jets in 2020, building on record output last year. It’s also going to retool an A380 superjumbo assembly line to make narrowbodies once the jet ends production next year. But that won’t provide additional capacity until mid-decade as some older A320 facilities are updated to meet higher build rates.

No airline wants Boeing to become an also-ran in the single-aisle sector. The Chinese-built C919 jet is behind schedule, as is the Russian Irkut MC-21. “It would be a disaster for everybody,” says Domhnal Slattery, CEO of jet-leasing company Avolon Holdings Ltd. The industry, he says, needs “healthy and relatively stable” competition.

The question for Boeing is how quickly it moves away from the 737, whose reputation is now tarnished. Blueprinting a new plane could sap funds needed in the future as the industry transitions to hybrid power. But without updated offerings, it could struggle to compete with Airbus.

Boeing CEO David Calhoun, who took over last month after the Max crisis led to the ouster of boss Dennis Muilenburg, will need to settle on a strategy soon, says Richard Aboulafia, an analyst at aviation consulting firm Teal Group. “Airbus is incredibly well-placed to capitalize on its single-aisle market position, and Boeing isn’t,” he says. “This is one of those enormously important inflection points, and they don’t really have long to make a decision.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Bret Begun at bbegun@bloomberg.net, Benedikt Kammel

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.