With Stocks Buybacks Halted, We’ll See How Much They Matter

With Stocks Buybacks Halted, We’ll See How Much They Matter

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Political sentiment in the U.S. has turned so viciously against share buybacks that they may never recover. Some worry stock returns will follow suit. But wagering on the death of American equities has usually been a sucker’s bet.

Always controversial, the sight of companies blowing precious cash on their own shares has become impossible to stand at a time when the coronavirus pandemic is spurring layoffs and raising bankruptcy risk. A lasting death knell may have sounded last week, when President Trump said he didn’t like it when proceeds of his 2017 tax cut were spent this way. Now Congress’s $2 trillion stimulus proposes barring any company receiving a government loan from repurchases until a year after it’s repaid.

It’s a watershed moment for buybacks, a tactic that—while done everywhere—has its fullest expression in American stocks, says Stephen Dover, head of equities at Franklin Templeton. Buybacks by U.S. companies represented 70% of cash returned to shareholders in the 12 months ended June 2019, according to Morgan Stanley. In Europe, where companies ladled out about $100 billion, they accounted for roughly 30%.

The S&P 500’s record of world-beating gains could be the first casualty, Dover says. “Probably going forward there will be regulation, or there will be limits to how much companies can do buybacks and pay dividends, and that will affect how much the market appreciates,” he says. “It could put the United States market on a more even playing field with overseas markets, where buybacks are less prevalent.”

Few topics in the market are this contentious. The impact of buybacks on everything from share prices and per-share earnings to the fabric of society are spiritedly debated, with easy answers elusive. On one side are claims that share repurchases brought a huge chunk of gains during the bull market, juicing executive compensation in lieu of investments elsewhere. Opponents say the impact is overstated; using cash to repurchase shares is just a value-neutral exchange of assets from one set of pockets to another, with little ability to increase overall wealth. Moreover, too few shares are bought to affect a market where $90 trillion of stock can trade in a year.

Which version is true has big implications, should buybacks go extinct. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. estimates $700 billion of shares were acquired in 2019 by U.S. companies, making them the biggest net buyer of equities.

A major salvo in the war over repurchases came in a 2017 paper by AQR Capital Management. It found no reason to assume buybacks drove the bull market. Evidence that they result in companies investing less in their businesses is scant, and because they’re often financed by debt, repurchases didn’t use up capital, said the authors, who include billionaire hedge fund manager Cliff Asness. The paper cited academic evidence showing that the announcement of a repurchase drives the associated stock up 1% or 2% on average—not an enormous effect, and one that may be explained in part by the vote of confidence in the company’s future that a buyback signals.

“There’s so many things that go into supply and demand for stocks, and what makes stocks attractive for investors, that viewing buybacks in isolation would miss a lot of the intrinsic value,” says Ed Clissold, chief U.S. strategist at Ned Davis Research. Eliminating buybacks “would make a difference. It would decrease demand for stocks. But if companies are growing earnings and are attractively valued, then there should be plenty demand for stocks.”

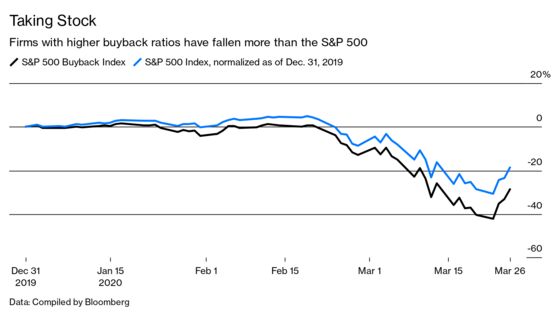

Companies with higher buyback yields—that is, those that return more money to shareholders via buybacks—typically perform in line with the market and trail it during times of turbulence, according to Maneesh Deshpande, head of U.S. equity and global equity derivatives strategies at Barclays. “Returning cash to shareholders aggressively makes a company riskier, hence the market rationally does not reward them with higher price performance,” Deshpande wrote in a note to clients. “During downturns these stocks underperform, and this has been starkly true during the current crises.”

Another knock on buybacks holds that they’re a way of manufacturing earnings per share growth by reducing outstanding stock, the denominator in the equation. This view also has dissenters. Ed Yardeni, founder of Yardeni Research Inc., has found evidence that companies hand out so much equity to employees that even with millions of shares bought back, any effect is almost canceled out.

One more criticism of buybacks—and one explanation for their rise—is that they’re a way of obscuring high levels of stock-based compensation to executives. There’s even evidence that some executives use short-term price bumps following buyback announcements to cash in their shares.

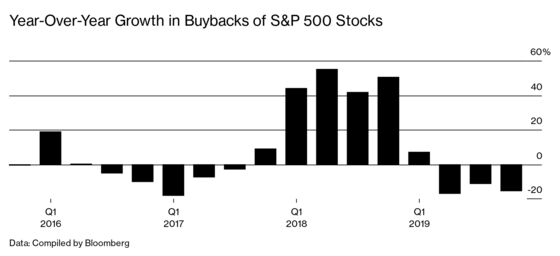

Many companies, unsure of how the pandemic will hit their bottom line, have suspended buyback programs, including Chevron, Intel, and Target. But even before the crisis, appetites had been waning for four years, excluding the tax-cut-fueled surge in 2018, according to Vincent Deluard, global macro strategist at INTL FCStone. Completed repurchases in the fourth quarter, the last before the coronavirus outbreak, had dropped by 15% year over year, Deluard wrote in a report.

The reason? Buybacks were looking too expensive. “The buyback era was already coming to an end,” he wrote. “Stretched balance sheets, absurdly high valuations, and nonexistent earnings growth were already good reasons not to repurchase stocks last year.”

Read more: Boeing Asks Washington for Help Critics Say It Doesn’t Deserve

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.