Attorney General’s Antitrust Power Play Is Just What Trump Wants

Attorney General’s Antitrust Power Play Is Just What Trump Wants

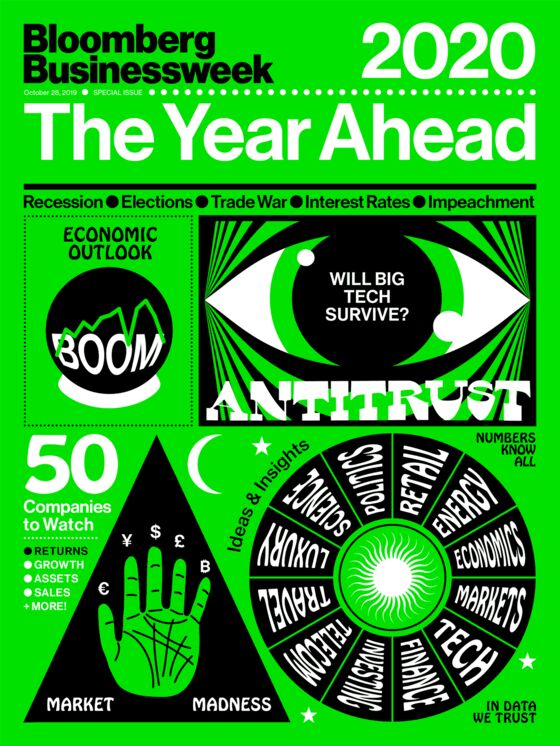

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The decision didn’t sit well with U.S. Attorney General William Barr. His antitrust chief in May had agreed to open probes of Google and Apple Inc., handing over Facebook and Amazon to the Federal Trade Commission, the rival antitrust agency a few blocks away.

Two months later, Barr did an end run around the agreement and made a grab for authority over all four tech giants. The Department of Justice announced wide-ranging reviews of the top social media, retail, and search platforms, which means Facebook Inc. and possibly Amazon.com Inc. will undergo parallel investigations by two agencies. The announcement enraged Mike Lee, the Utah Republican who oversees antitrust on the Senate Judiciary Committee. In a hearing, Lee berated FTC Chairman Joe Simons and the Justice Department’s antitrust chief, Makan Delrahim, for piling on the companies with overlapping investigations.

Barr’s power play, described by two senior officials involved in the cases, shows the attorney general is taking a direct role in the probes of America’s biggest tech companies. At the same time, Barr is doing what’s become his trademark as the U.S.’s top law enforcement official: delivering on the agenda of President Trump, who’s agitated for tech investigations since his election.

Those companies may have more to fear now that they’re pitted against a single, determined law enforcement agency in addition to a more ponderous, five-member commission that acts mostly on consensus. The Justice Department has about 50 people working on the tech antitrust cases, says a person familiar with the matter. Barr has assigned his No. 2, Jeffrey Rosen, to oversee the investigations, and he promoted a lawyer in the antitrust division to his personal staff to advise him.

It’s unusual for an attorney general to play such a hands-on role in an antitrust inquiry. But Barr isn’t typical. Since taking over Justice in February, he’s emerged as one of the president’s most assiduous defenders. In March his characterization of the conclusions in special counsel Robert Mueller’s report on Russian interference in the 2016 election allowed Trump to declare vindication but drew a rebuke from Mueller. He could play a pivotal role in defending Trump as the House impeachment inquiry unfolds.

Barr’s actions are consistent with his view of an agency whose job is to defend Trump’s executive power, says Donald Ayer, who was deputy attorney general under George H.W. Bush. “He’s got a vision of the president as all-powerful in a way that makes an independent Justice Department not possible,” says Ayer, citing a 2018 memo by Barr in which he argued that the president can control federal investigations, including of the president. A Justice Department spokesman denies the tech company probes are politically motivated, pointing to widespread bipartisan concerns among state attorneys general.

Other actions have quieted some critics. The U.S. attorney’s office in Manhattan, for example, is investigating the financial dealings of one of Trump’s closest associates, former New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani, according to a U.S. law enforcement official.

Big Tech presents legitimate antitrust issues, says Jeff Blumenfeld, a lawyer at Lowenstein Sandler in Washington, but the department’s scrutiny is part of a pattern that makes it look politically driven. Trump has repeatedly accused technology platforms of silencing conservative views. He’s also attacked Amazon, whose founder, Jeff Bezos, owns the Washington Post, a target of Trump’s diatribes about biased reporting. A cloud of uncertainty sits “over everything, over why investigations are being pursued. How are targets being chosen? Do we believe what they say are the facts?” Blumenfeld asks.

At his confirmation hearing in January, Barr said: “I think a lot of people wonder how such huge behemoths that now exist in Silicon Valley have taken shape under the nose of the antitrust enforcers.” As general counsel at Verizon Communications Inc. and its predecessor from 1994 to 2008, Barr clashed with tech companies over open-internet rules, known as net neutrality, which prevented Verizon and other internet service providers from slowing down traffic or charging users higher fees.

He was among those who argued unsuccessfully against such rules, then watched as companies such as Google, whose traffic depended on telecom networks, and which led the charge for net neutrality, grew to become some of the world’s most valuable. Trump’s Federal Communications Commission withdrew the rules in 2018.

Barr isn’t out for revenge, says Paul Cappuccio, a former general counsel of Time Warner Inc., where Barr was a board member. He’s “had experience with antitrust laws that have worked really well, and he’s had experience with antitrust laws that have overreached,” says Cappuccio, who’s spoken to Barr since he became attorney general. “His background could just as easily lead one to think he might be skeptical of the risk of overenforcement.”

Barr is the first U.S. attorney general in recent memory with a background in competition policy. His career has included work on two U.S. Supreme Court cases involving antitrust and telecom. For most of that time, he fought to protect the phone companies from competition. He also played a key role in reconsolidating an industry that had been split into pieces in the 1984 court-ordered breakup of AT&T Inc., according to lawyers and former government officials familiar with his work.

“Barr was very effective in undermining the development of competition, and thus protecting the Bell companies from the competition Congress intended,” says Chris Wright, a former FCC lawyer who faced off against Barr over implementation of the Telecommunications Act of 1996.

While he fought to shield phone companies from rivals, Barr also argued for wider access to cable networks that were providing internet service to homes. At a 1999 congressional hearing, he sounded like an antitrust crusader as he complained about the “grossly anticompetitive” tactics of cable companies that required customers with cable modem service to also pay for the companies’ internet service. That was a form of improper product-tying that reduced consumer choice, he argued.

“Once a firm gets a head start in closing off competition,” Barr said, “the results can take years to undo. In fast-growing network industries, anticompetitive tactics can lead to disastrous results very quickly.”

That mirrors today’s worries about technology markets. The companies are so vital to the U.S. economy, the Justice Department is compelled to scrutinize them, says Rosen, Barr’s deputy. “You can just look at the numbers of users of the leading search engines, social media platforms, retail providers—the number of users is just massive,” he says.

Gene Kimmelman, an Obama administration antitrust official, says Barr is watching history repeat itself. “He’s well-versed in arguments of the dangers of leveraging power in one market to either block entry or advantage yourself in an adjacent market,” Kimmelman says, referring to the cable companies. “Those are precisely the kind of issues that are being raised about the tech platforms.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Paula Dwyer at pdwyer11@bloomberg.net, Sara FordenDimitra Kessenides

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.