Tight-Lipped Sinema Rivals Manchin as Democrats’ Wild Card

Tight-Lipped Sinema Rivals Manchin as Democrats’ Wild Card

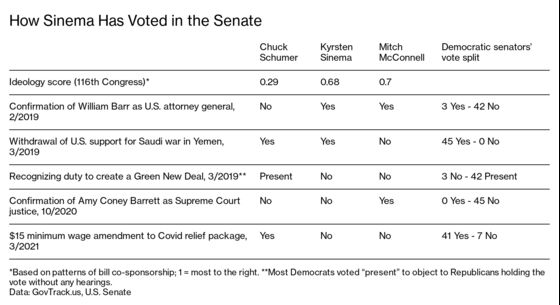

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Kyrsten Sinema likes to make a statement. The 44-year-old senior senator from Arizona wore brightly colored wigs in the Capitol last year after hair salons shuttered because of Covid-19. Voting in March on whether to increase the minimum wage to $15 an hour, the centrist Democrat riled progressives by giving a curtsy and a playful thumbs-down. And last month she posted a picture of herself on Instagram sipping sangria and sporting a gold ring adorned with a profane message intended, presumably, for her critics: “F--- Off.”

But when it comes to where she stands on the issues, Sinema—who holds the power to quash any element of President Joe Biden’s agenda by withholding her vote in a 50-50 Senate—is something of a mystery. The other Senate Democrat most likely to split with his party, Joe Manchin of West Virginia, appears frequently on Sunday talk shows to discuss policy and navigates the Capitol’s corridors with reporters in tow. By contrast, Sinema is tight-lipped and seldom seen except on the Senate floor or inside committee rooms. (Spotted and asked if she would talk to Bloomberg Businessweek for this piece, she responded, “I have no interest in that.”)

Now the question is just how much of an impediment Sinema will be to the Democrats’ agenda. Her staunch opposition to eliminating the Senate filibuster casts doubt on whether the Democratic leadership can carry through on Biden’s campaign promises on voting rights, an immigration overhaul, new gun control measures, and a grand economic plan.

Among Democrats in her home state, there’s growing frustration with her interest in bipartisan dealmaking when there’s scant evidence of it in Congress. “I want Kyrsten Sinema to be a champion for progressive causes and to make change,” says Michael Slugocki, vice chair of the Arizona Democratic Party. “I want her to make the most of it and not be caught up in procedural issues like the future of the filibuster.”

Yet longtime observers and allies say to expect the senator to use the same approach that helped her score a remarkable win in 2018: She’ll keep her own counsel, ignore much of her party’s leftward pull, and demonstrate a frequent regard for the desires of independent and Republican constituents.

The first Arizona Democrat elected to the Senate in a generation, and the first openly bisexual U.S. senator, Sinema has undergone a dramatic political evolution since the early 2000s. Depending on whom you ask, she’s either caved on liberal principles or recognized the value of pragmatism.

“It is a combination of rigorous discipline coupled with ambition,” says Chuck Coughlin, a veteran GOP strategist in Phoenix who became an independent in 2017 and who’s watched her transformation. Sinema, he says, seems to be working to match the “maverick” image of another Arizona senator, the late John McCain.

Born in Tucson and raised in Florida, Sinema entered politics as a Green Party antiwar activist in Phoenix. After two unsuccessful runs for public office, she switched to the Democratic Party and won a seat in the Republican-dominated Arizona House of Representatives in 2004 at age 28. She served six years and became known as a champion of marriage equality, raising $2.5 million to help defeat a 2006 proposal to ban same-sex marriages, before advancing to the state senate.

Trained as a social worker and lawyer (she’s since earned a Ph.D. in justice studies), Sinema learned early during her time in the state legislature that she needed Republican support to move bills, says Rich Crandall, a former Republican state lawmaker who worked with her on legislation. She was creative in forging relationships, Crandall says, inviting new lawmakers to volunteer at a Phoenix soup kitchen.

She also stood out in the Democratic caucus as the person who knew every technical aspect of a bill: “Her modus operandi is to know her subject really, really, well,” Crandall says. “Kyrsten always thrived on the details, the weeds, the wonk.”

Chad Campbell, a lobbyist and former Democratic leader of the Arizona House of Representatives who served with Sinema, says she was skeptical of one-party solutions that might be overturned if the legislature changed hands. “She wanted to achieve long-standing policy solutions, as opposed to solutions that were one-sided and had partisan foundations,” Campbell says. Another former Democratic state legislator who worked with Sinema, Steve Farley, says she focused on issues she could get bipartisan support for, including the needs of veterans and domestic violence.

Sinema ran for the U.S. House in 2012 in a newly drawn district in south-central Arizona that was almost evenly split between the parties. After winning, she cemented her move to the center, joining the moderate Blue Dog Coalition and the bipartisan Problem Solvers Caucus. She didn’t vote for Nancy Pelosi in 2015 and 2017 speaker elections, voted with Republicans to loosen some regulations, and supported a law to boost penalties on immigrants who illegally reenter the U.S. after being deported. She did vote with her party against a repeal of Obamacare and against the 2017 Trump tax cuts.

In the 2018 Senate race for the seat of retiring GOP Senator Jeff Flake, Sinema beat Republican Martha McSally with just a two-point margin after voters weren’t swayed by McSally’s attacks on Sinema’s left-wing past. Campaigning in a state with roughly equal shares of Republicans, Democrats, and independents, Sinema rarely brought up her party affiliation.

In the Senate, she voted against the Green New Deal in 2019, one of just three Democrats in the chamber to do so. In 2019 and 2020, the Arizona Democratic Party considered censuring her for her frequent votes with President Trump and congressional Republicans, including her vote to confirm William Barr as U.S. attorney general. The resolution was tabled.

Now with Democrats in the majority for the first time in her career, some in the party say her opposition to altering rules on the filibuster, which requires a 60-vote threshold to advance legislation, is out of step with shifts in a state that just elected another Democrat, Mark Kelly, to the Senate. A poll conducted in late February by the left-leaning firm Data for Progress found that 61% of likely Arizona voters say passing major bills is a high priority and just 26% say it’s more important to preserve the Senate tradition.

“It’s frustrating,” says Emily Kirkland, executive director of the group Progress Arizona. “The reason she is receiving so much attention and has such outsized influence is tied to the fact that she is so out of step with Arizona voters.”

For the time being, Sinema is keeping everyone guessing about what she might do on many agenda items Democrats want, including Biden’s $2.25 trillion infrastructure and jobs plan and his $1.8 trillion American Families Plan. Senate Democrats could agree to take a parliamentary shortcut called reconciliation to pass portions of those, but she hasn’t indicated she would back that.

Biden hosted her at the White House on May 11 to talk about the American Jobs Plan. At the Capitol after the meeting, she told reporters: “It was great. He gave me cookies.” (Asked what kind, she responded, “chocolate chip.”)

Sinema is also taking part in bipartisan talks to seek compromises on such issues as immigration reform, and working with some top Republicans on legislation. She recently introduced a bill with Senator John Cornyn of Texas to provide the government with more resources to address the wave of migrants at the border with Mexico. Another frequent Republican partner is Utah Senator Mitt Romney. They’ve co-sponsored legislation to curb student debt and are working on a proposal to raise the minimum wage, perhaps to $11 an hour.

While almost all other Senate Democrats support ending the filibuster, senior lawmakers in the party say they’re fully aware that Sinema represents a Republican-leaning state and they wouldn’t have a majority without her. “There is a recognition in our caucus that this is not an easy state for a Democrat,” says Senate Finance Committee Chair Ron Wyden, an Oregon Democrat. “The challenges of states like Arizona in a 50-50 Senate are going to be consequential all the way through this session of Congress.”

Goth is a reporter for Bloomberg Government.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.