Why Trump’s Tariffs Didn’t Help Create More Steel Jobs

Why Trump’s Tariffs Didn’t Help Create More Steel Jobs

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Visiting the massive steel mill in Crawfordsville, Ind., operated by Nucor Corp., the largest American steelmaker, helps explain why the much-ballyhooed steel tariffs promoted by Donald Trump have so far been a bust for the steelworkers he successfully courted in his 2016 presidential bid. The Crawfordsville facility, set amid sprawling acres of farmland, looks like many other plants. But the 30-year-old factory has the ability to shrink or expand production at will, depending on demand by customers, while employing pretty much the same number of workers.

That flexibility is why, as the first year of Trump’s steel tariffs comes to a close, the U.S. industry’s biggest players are enjoying increasing demand and revenue but adding few of the jobs promised during the campaign. “They’re expanding production, demand is really strong in the country, and crude steel production will rise as imports remain low, but they’re not hiring much,” says Cicero Machado, a steel analyst at metals researcher Wood Mackenzie. The firm forecast that the number of U.S. steel jobs barely budged last year despite a bump in output from the tariffs.

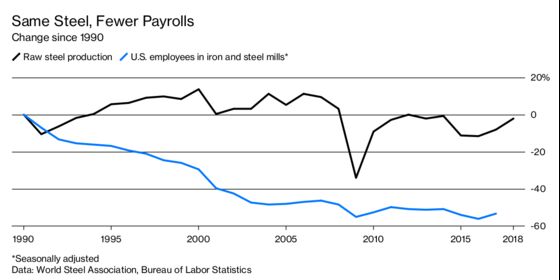

The number of employees at the country’s iron and steel mills has tumbled 53 percent since 1990, to 87,700 in November 2018, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, whereas U.S. steel production dropped only 2.2 percent in the same period, according to the World Steel Association.

Throughout his presidential campaign, Trump told voters in industrial battleground states such as Ohio and Indiana that he would enact trade policies that would spark a revival in steel jobs. In February 2018 the Commerce Department determined that steel imports threaten the viability of the American steel industry, endangering U.S. national security. So the department recommended Trump impose 24 percent tariffs on imported steel to boost capacity utilization among domestic producers to 80 percent, from about 74 percent. Nucor Chief Executive Officer John Ferriola told Bloomberg News in May that an 80 percent capacity utilization level was “the minimum needed for the industry’s long-term financial health and viability.”

The tariffs, which have made imported steel more costly, are having an impact. The American Iron and Steel Institute (AISI), a trade group, reported that average capacity utilization industrywide touched the 80 percent level in the first week of 2019, up 7 percentage points from a year earlier. That’s one reason analysts expect U.S. Steel Corp. to report a 175 percent jump in 2018 profit, to $936.2 million, on Jan. 30.

Yet Wood Mackenzie predicts that while steel production rose 4 percent, the total number of American steel jobs increased just 1 percent in 2018. “I was expecting much more jobs to be created,” Machado says.

One reason for the employment sluggishness: Producers remember the pain suffered after the financial crisis and the subsequent collapse in commodities demand, which precipitated massive cost cutting and significant job losses. So as they enjoy today’s tariff-induced boost in demand, many are selling the excess capacity at their underutilized plants while keeping a lid on payrolls. Nucor, for instance, says it has more than enough current employees at its Crawfordsville plant to keep the factory running around-the-clock, and it has no plans to add workers. “It takes the same amount of people to run a blast furnace or an electric arc furnace at 100 percent utilization or 70 percent utilization,” says Curt Woodworth, a steel analyst at Credit Suisse. The industry is “just turning up the dial on capacity.”

Growing productivity among American steelmakers is another reason they can do more with the same number of—or fewer—employees. U.S. workers produced about 478 tons per person in 1990, when about 185,400 people worked in the industry, according to government data. By 2018, production had hit almost 1,000 tons a person, with 87,700 workers in the sector. This means that in less than 30 years, steelworkers have become twice as productive.

To be sure, some plant expansions have been announced, which portend new jobs, and steelmakers have been careful to tie the tariffs to those additions. Nucor has announced multiple expansions at existing plants and several new plants. The company says that one it announced in January was made possible in part because of Trump’s policy. But Nucor also stressed that it made these decisions because of longer-term trends in which it sees consumption growing for the next few years.

U.S. Steel reopened two blast furnaces last year, which Trump attributed to his tariffs. However, the company said the decision was more broadly due to “market conditions and customer demand,” including the impact of tariffs. Likewise, Steel Dynamics Inc. told investors in January that a plant it’s building will be viable regardless of future U.S. trade policy.

Analysts are skeptical that domestic steelmakers would make these long-term capital expenditures solely on the basis of trade tariff policy that could end when Trump leaves office—or before. “I think the steel companies are looking at expansions as a multiyear thing, and they see free cash flow the next several years, and they’ve been looking to reinvest. So they’ve got multiple motivational factors supporting that decision,” says Woodworth at Credit Suisse.

While employees haven’t benefited much from Trump’s policy, surprisingly neither have shareholders. The price of steelmakers’ stocks tumbled last year. Nucor’s fell about 19 percent, its worst annual decline since the Great Recession. U.S. Steel’s fell 48 percent, and AK Steel’s dropped 60 percent.

As producers boosted capacity utilization to 80 percent, investors worried the increases would result in too much supply for an economic cycle that’s peaked. Adding in new plants, Keybanc Capital Markets estimates that about 10 million to 15 million more tons of annual capacity will come online over the next three to five years, or about a 15 percent increase from 2018’s total production.

“The reason why investors hate the industry right now is they hate those numbers,” says Phil Gibbs, a steel analyst at Keybanc. “To fulfill that supply gap, you’ll need more import displacement [replacing imports with domestic-made steel], a stronger economy, and you’ll probably need some infrastructure spending. It’s why steel investors haven’t responded in kind and don’t want to have anything to do with the sector.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Ellis at jellis27@bloomberg.net, Howard Chua-Eoan

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.