Why the Crime of Slave Stealing Still Matters

Why the Crime of Slave Stealing Still Matters

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- People were property in the plantation South. Everybody knows that. But let’s consider the logical consequences. Suppose you were to help an enslaved worker escape. What crime have you committed?

The answer is theft.

It makes a bizarre, painful sort of sense. Under the ideology of slavery, if you assist in an escape, you’ve taken what is legally someone else’s property. You’ve stolen chattel. In the eyes of a slaveholder, you’re not a noble freer of captives. You’re a petty criminal, no better than—for example—a cattle rustler. “Slave stealing,” the law called it, or, in some places, “man stealing.” And the theory behind it has implications even today.

Theft of a slave was a crime against property, like burglary or arson. In many instances, those who helped free the enslaved were prosecuted simply for larceny. Penalties were harsh. A few states allowed the offender to be put to death, but those convicted were more commonly sentenced to lengthy stays in the dreadful penitentiaries of the day.

Southern states considered slave stealing “a despicable practice.” Small wonder. If a slave could be “enticed”—a common term at the time—into running away, then perhaps the slaveholder’s human property was ... well, human. But if a contradiction existed, the law ignored it.

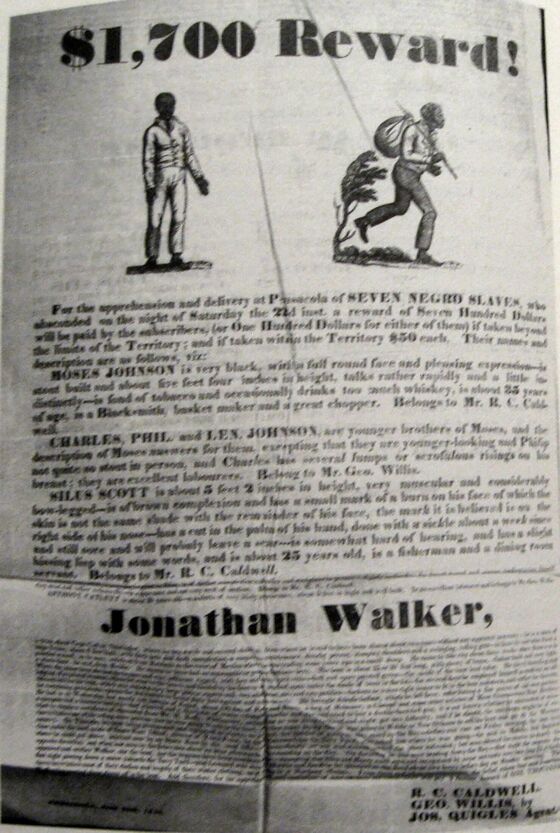

The more spectacular prosecutions were widely reported in the newspapers. In June of 1844, a ship’s captain named Jonathan Walker set sail from Pensacola only to be brought back to Florida in chains, accused of stealing seven slaves. In fact, Walker was an abolitionist and had intended to carry the captives to freedom. A federal judge ordered that he be pilloried and that his palm be branded with the letters “SS” (for “slave stealer”). In later years, Walker became a popular speaker on abolitionism. At the conclusion of his remarks, he would hold up his palm to display the brand and tell the audience to behold “the coat of arms of the United States.”

And yet one might argue that branding was a light punishment. In 1861 a Missouri court convicted a Black man of grand larceny for helping slaves escape. He was sentenced to five years in the penitentiary. In a similar case, a judge in Richmond, Virginia, handed down a sentence of six years. The 1849 slave-stealing trial in a Tennessee courtroom of the Quaker abolitionist Richard Dillingham made nationwide headlines. He was convicted and sentenced to three years.

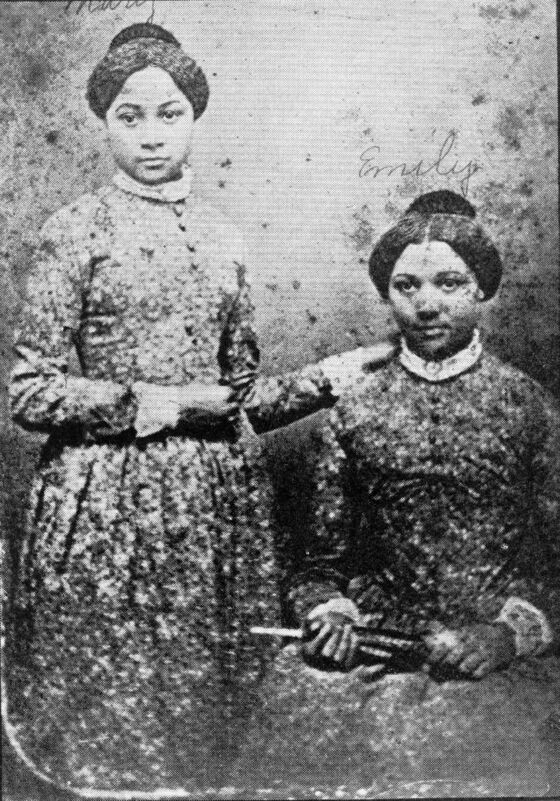

Perhaps the best-known prosecution involved Daniel Drayton, captain of the ship Pearl, which tried to transport from the District of Columbia around 75 slaves (historical accounts differ). It was the largest group of escapees in a single nonviolent flight in the nation’s history. So famous was the episode that it inspired scenes in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. At Drayton’s 1848 trial, his lawyer claimed that there had never been a prosecution under the District’s statute, a law he described as “waked up, after a slumber of more than a century.” No matter. Unable to pay the ruinous fine, Drayton and his co-defendant were remanded to prison for an indefinite stay. After serving four years, they were pardoned by President Millard Fillmore.

The abolitionist Charles Turner Torrey found a clever way to stand the phrase “man stealing” on its head. Because of his work helping slaves free themselves, he was convicted of stealing them and ordered to serve six years, although he would die of tuberculosis a year and a half into his sentence. While behind bars, he wrote a letter to a fellow pastor arguing that it was actually the enslaver who was guilty of man stealing—by holding the worker against his will and refusing to pay him wages.

Slave owners and their supporters complained that the “thefts” were being committed by outsiders. In this they had a point. One study of those convicted of slave stealing in Missouri found that the majority came from free states and four came from foreign countries.

To be sure, there were also less scrupulous “slave stealers,” who by force or trickery kidnapped the enslaved and resold them elsewhere. The trickery often involved a promise, in the words of one observer, “with the story that he was being transported by a friend to a free state.” One of the best-known kidnappers was a Black man, Madison Henderson, who after over a decade of hoodwinking the enslaved was executed. But here’s the irony: Although we nowadays think of the villains as kidnappers, they couldn’t be prosecuted for that crime. Kidnapping was the taking and detainment of a human being. The victims happened to be Black and enslaved, and thus property, and so they could only be stolen.

It’s an error to draw too much from history, but it’s also an error to draw too little. By remembering that helping the enslaved escape was theft because those who fled were mere property, we can gain a useful insight into the troubles that roil us today: The burden of a past in which Black people were less than human has yet to fade.

Carter, a law professor at Yale University, is a Bloomberg Opinion contributor.

Read next: America’s Policing Budget Has Nearly Tripled to $115 Billion

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.