Why the Saudis Are Embracing Sports

Why the Saudis Are Embracing Sports

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- On Jan. 5 the Saudi port of Jeddah echoed with the roar of hundreds of cars, motorcycles, and trucks in the Dakar Rally, a grueling two-week trek through the mountains and deserts of the kingdom—the first time the event is being held in the Middle East. That came just four weeks after the “Clash on the Dunes,” a heavyweight boxing title bout near the ancestral home of the Saudi ruling family, which was billed as a worthy successor to Muhammad Ali’s “Rumble in the Jungle” and “Thrilla in Manila.” And on Feb. 29, 14 thoroughbreds will take to a dirt track in Riyadh for the inaugural Saudi Cup, the world’s richest horse race, with $20 million up for grabs.

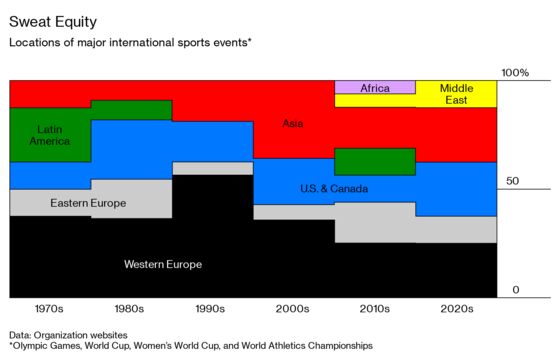

The run of big-ticket events marks a sharp turnaround for the kingdom, which barely registers on the global sporting map. It’s part of a push by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the 34-year-old de facto ruler, to modernize the economy and reduce the influence of puritanical Islam. The prince says opening up to tourists and allowing Western-style entertainment and concerts that Saudis have long been denied can create much needed jobs and attract investment beyond oil—though the risk of wider conflict after the U.S. killed Iranian General Qassem Soleimani could threaten his ability to achieve that. The Saudis aim to raise non-oil revenue more than sixfold annually, to $266 billion by 2030.

Critics call the effort “sportswashing”—an attempt to deflect attention from the kingdom’s role in the war in Yemen, now in its fifth year, and the 2018 murder of Washington Post journalist Jamal Khashoggi by Saudi agents. “It’s a soft-power strategy to project a kinder face,” says Madawi Al-Rasheed, a frequent government critic working as a visiting professor at the London School of Economics. “They’re using it to cover up some serious shortcomings.”

The plans echo those of Middle Eastern rivals, which have long seen sports as a way to boost their profile. Dubai has hosted international golf, tennis, and rugby tournaments for decades. Bahrain and Abu Dhabi have Formula One races, and the latter in 2010 opened a Ferrari-linked theme park with a marina and luxury hotels next to the circuit. Qatar is investing $200 billion in stadiums and other infrastructure for the 2022 soccer World Cup.

The strategy risks attracting more scrutiny than the Saudis are accustomed to. Human Rights Watch called on the Dakar Rally organizers to use the event to highlight the mistreatment of female activists. Former players have slammed the Royal Spanish Football Federation for a $130 million deal that will see Barcelona, Real Madrid, and two other teams play in the kingdom on Jan. 8-12; citing the Saudis’ record on human rights, Spain’s state broadcaster refused to show the tournament, to be held annually for the next three years. Golfer Phil Mickelson has come under fire for competing in the Saudi International tournament in January (unlike Tiger Woods, who declined an offer of $3 million just to show up, and Rory McIlroy, who said “morality” was part of his decision to skip the event). “I’m excited to go play and see a place in the world I’ve never been,” Mickelson wrote on Twitter.

Still, the experience of other rising nations suggests sports investment pays off. The 1988 Seoul Olympics and the Beijing Games two decades later presented a softer side of those countries, and the Chinese are seeking a repeat with the winter version in 2022. While Qatar has taken flak over its treatment of immigrant workers building World Cup stadiums and allegations of corruption in the bidding for the tournament, its reputation as a center of tourism and culture is growing. “The Saudis don’t want their political record in the spotlight,” says Anoush Ehteshami, director of the Institute for Middle Eastern & Islamic Studies at Durham University in England. “But it’s committed to getting the world’s interest economically. You can’t do that without opening up.”

The push comes as Saudi Arabia’s isolation following Khashoggi’s killing starts to ease. Many Westerners skipped the 2018 Future Investment Initiative, a Davos-like conference hosted in Riyadh, but the 2019 meeting in October was attended by the likes of U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and the heads of Citigroup Inc. and BlackRock Inc. A few weeks later, Citi joined Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and other global financial houses to manage energy giant Saudi Arabian Oil Co.’s $26 billion initial public offering. “Some sports or institutions will decide they just can’t do business in Saudi Arabia, but they’ll be in the minority,” says Ryan Bohl, who analyzes the Middle East for Stratfor, a political advisory firm in Texas.

The country’s sports drive may dovetail with big-name sporting acquisitions abroad, says Simon Chadwick, a professor of sports enterprise at the U.K.’s Salford Business School. Saudi Arabia has so far stayed out of the race for soccer teams and naming rights that other Persian Gulf countries have engaged in. Qatar in 2011 paid $140 million for France’s Paris Saint-Germain and has since invested more than $1 billion in the club and A-list players such as Brazil’s Neymar. And Abu Dhabi, which effectively owns English champions Manchester City through a senior member of the emirate’s royal family, has named the club’s stadium after its national airline, Etihad. With some $160 billion in oil revenue this year, Saudi Arabia has the clout to catch up. It will be hard for any business—including sports—to ignore, Chadwick says. “The thing that speaks most loudly is money,” he says. “If the money’s in Saudi Arabia, sport will go there.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: David Rocks at drocks1@bloomberg.net

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.