Why Investors Have Become Skittish About Turkey

Why Investors Have Become Skittish About Turkey

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The world is finally catching on to what the skeptics in Turkey were saying all along.

For the better part of 16 years, Turkish leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan, a self-styled economic reformer and the world’s great hope for Muslim democracy, had a compelling story—and for most of that time, everyone bought it. Everyone, that is, except Turkey’s old guard—the secular establishment, the billionaires, generals, and educated elites who stood to lose their monopoly on power, wealth, and influence.

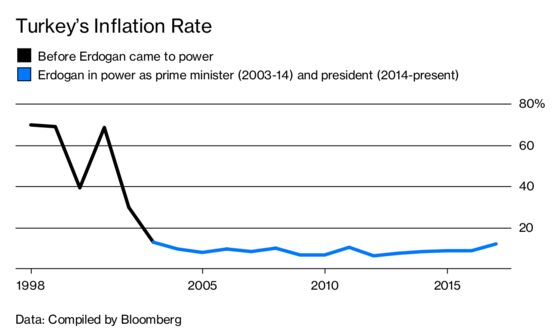

The old establishment hadn’t done well by the rest of the populace or the economy. When Erdogan’s party swept to victory in 2002 on pledges to open markets and liberalize institutions, Turkey’s economy was on life support, requiring an international rescue package that topped $20 billion. The lira had collapsed, along with a handful of banks and government efforts to contain raging inflation.

Voters demanded change. They got it. For most of Erdogan’s years in power, Turkey appeared to be in a golden age. Istanbul, a global crossroads for centuries, exuded optimism. Restaurants and clubs popped up like mushrooms. Entire new districts for the arts and nightlife seemed to sprout overnight. Young Turks educated abroad returned in droves to start businesses and make their fortunes. Turkey hosted international summits and, with Spain, became a co-sponsor of a United Nations-backed effort to forge international, intercultural, and interreligious dialogue and cooperation. It was captivating. So much so that a visitor could be forgiven for believing that under Erdogan, the city finally had a chance at living up to Napoleon Bonaparte’s comment: “If the world was only one country, Istanbul would be its capital.”

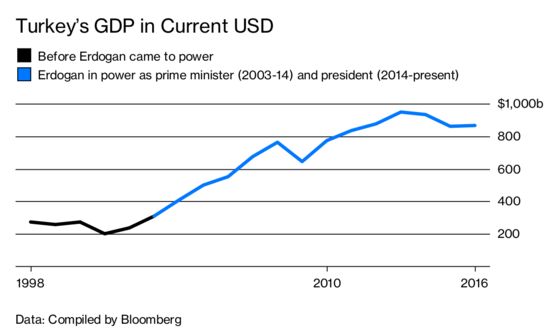

Now, however, it looks like Turks got more than they bargained for. After a run that brought in more than $220 billion of foreign investment, tripled gross domestic product, and returned inflation to single digits, Turkey’s economy is again ailing—its democracy even more so.

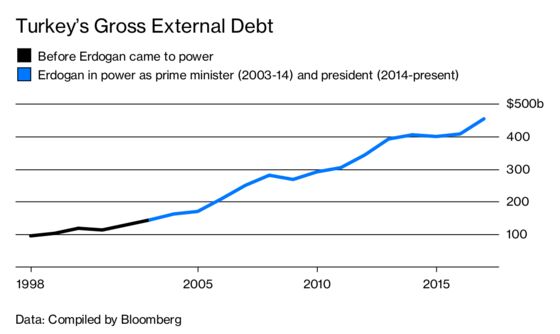

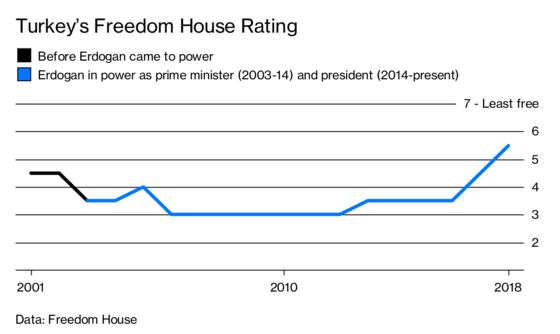

With the nation heading to snap elections on June 24, the lira is sinking, inflation is running at double the central bank’s target, and companies are struggling under more than $300 billion in foreign debt. Turkey’s ranking on nearly every index of democratic governance has plunged. There’s no longer talk of a peace process with Kurdish separatists. Buoyed by a seeming imperviousness at the polls, Erdogan has become ever more autocratic, his style of leadership more personal, prickly, and intolerant. He has ruled using emergency law since a failed military coup in the summer of 2016, jailing more journalists than any country in the world and widening censorship powers to include the internet.

As Erdogan’s resistance to criticism has increased, so has his confidence in his own opinions. The 64-year-old president traveled to London in May to meet executives, bankers, and investors who expected to hear comforting words to calm their concerns. Those hoping for the all-clear are still waiting. The lira tumbled after his blunt public message: He expects to take more control of the economy after the June elections, especially when it comes to the independence of Turkey’s central bank.

In an interview with Bloomberg Television in London on May 14, Erdogan doubled down on his unorthodox view that cutting interest rates would solve Turkey’s inflation problem. He has routinely criticized the central bank for setting interest rates that he says have helped stoke rising prices, an argument that contradicts conventional economic theory. “Of course our central bank is independent,” Erdogan said in the 30-minute conversation. “But the central bank can’t take this independence and set aside the signals given by the president.”

Such self-assurance isn’t out of character for a politician who built himself a palace four times bigger than France’s Versailles, and defended its $615 million cost by comparing it to Buckingham Palace. It’s from that new abode that the onetime mayor of Istanbul has virtually crowned himself the unassailable leader of a country of 80 million. As Erdogan’s hold over the Turkish economy grows, so will the threat to the country’s recent decade and a half of prosperity as investors and a generation of young talented Turks flee.

It wasn’t always thus. In the years after his election as prime minister, investors from all over wanted in: Following International Monetary Fund prescriptions, Erdogan had stabilized the economy and the money followed, helping fuel an average annual growth rate of 5.8 percent. In 2005, European leaders began negotiations with Turkey for full membership in the European Union, offering the prospect of becoming its first Muslim-majority member.

Beneath the surface, though, ran a current of doubt among the elites who profited in the ancien régime. Elbowed aside by a new generation of connected builders, doers, and fixers, the old guard whispered among themselves that it was all a show. This new sultan, they said, really wanted to subjugate the army, take over the courts, and Islamify the country. They warned of a looming Iran-style theocracy. An oft-cited quote whose provenance was never clear—but which Erdogan has never disavowed—had him once telling supporters: “Democracy is like a streetcar. You ride it to your destination, and then you get off.”

On his way to winning elections at all levels—presidential, general, and local—criticism from the secularists in the big cities only made him more appealing to his pious base in the heartland. But the foundations of the Erdogan miracle began to crumble the moment the supremely confident politician realized that people were willing to take their disagreements with him to the streets.

The overthrow of the democratically elected Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt in the aftermath of the 2011 Arab Spring changed the way Erdogan looked at dissent in his own country. His anxiety found full expression in the increasingly autocratic ways that continue to this day.

In May 2013 a plan to destroy a 9-acre green space in central Istanbul, a city that had been ravaged by a decade-long orgy of construction, set off what would become known as the Gezi Park protests. Unwilling to let himself become a victim of popular unrest, Erdogan used heavy-handed police action against a smattering of environmental activists. It backfired and sparked a mass movement that saw demonstrations seeking to bring Erdogan down in nearly all of Turkey’s biggest cities.

Instead of the strong reformer, the world now saw a vindictive ruler whose actions exuded paranoia. Erdogan’s entourage floated conspiracy theories about the protests; one claimed that Germany had funded them because it was jealous of Turkey’s new airport. One adviser claimed that Erdogan’s enemies were trying to kill him using telekinesis. Police retook Gezi Park, but Turkey would never be the same. The end of the golden years was at hand.

The sense of optimism, the belief that Turks of various stripes and ideologies were all in the same boat, was replaced by a relentless divisiveness in political culture, exacerbated by a sense of grievance emanating from their uncompromising leader. Erdogan has veered hard toward a version of Islamic nationalism that would have been unthinkable just years before. He organized takeovers of major media groups by his allies, backed religious schools, and went on a jailing spree against anyone showing even the slightest sign of dissent. He blocked Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, and Wikipedia. Turkey became the global leader in requests to block content on social media. Some Turks are choosing to leave rather than live in what they fear is an emerging dictatorship.

Then the strains between Erdogan and his political partners—followers of a cleric named Fethullah Gulen, who lives in self-imposed exile in Pennsylvania—erupted into open political warfare. Dozens of tapes were leaked alleging corruption among Erdogan’s family and closest contacts. Erdogan labeled the investigation led by Gulenist prosecutors a coup attempt. He arrested police, sent prosecutors into hiding, and purged the courts. By February 2014 ministers accused of pocketing tens of millions of dollars in a scheme to help Iran evade U.S. sanctions were casting votes in Parliament to give themselves more control over the judiciary. The probe was killed, but the battle had just begun.

The Gulenists went underground, but they didn’t go away. In July 2016 a faction of Gulenist officers in the military launched an actual coup, bombing Parliament with air force jets, blocking a bridge in Istanbul with tanks, and killing more than 200 people. Appearing on television via a mobile phone app, Erdogan called his supporters onto the streets and asked them to stay there for weeks on end.

The purges that followed decimated Turkey’s institutions and further strained relations with its Western partners, most notably Germany and the U.S.; each had citizens swept up and thrown in prison. Tens of thousands of Turks were jailed. Countless others lost their jobs. Hundreds of businesses were seized or shut down. The crackdown on the press and freedom of expression intensified.

For Erdogan, the betrayal led him to lean increasingly on an inner circle of advisers and functionaries whose main qualification for their jobs is loyalty. When managers from two major investment funds visited Ankara earlier this year, they reported being shocked at how political loyalists have gained the upper hand against seasoned pros in the nation’s most important policymaking bodies, according to an economist familiar with the visit. The economist’s conclusion: “Textbook institutional decline.” ● Harvey is the Bloomberg News Turkey bureau chief.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Howard Chua-Eoan at hchuaeoan@bloomberg.net, James Hertling

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.