The Real Pain From Trump’s Tariffs Trickles Down to Consumers

The Real Pain From Trump’s Tariffs Trickles Down to Consumers

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- For a big country such as the U.S., slapping hefty tariffs on imports can make sense under certain conditions. If many foreign suppliers are competing for sales in the U.S., they could be willing to absorb the cost of a tariff to maintain market share—sacrificing their own profit margins while the U.S. Treasury pulls in extra tax revenue. The logic of the “optimal tariff” is that “the U.S. is often a large enough importing country that we can throw our weight around,” says Thomas Pugel, an economist at New York University Stern School of Business.

The theory of optimal tariffs, which has figured in economic thinking since the 1840s, fits snugly into the worldview of President Donald Trump, who often says America’s trading partners have taken advantage of the U.S. On Sept. 17 he told reporters, “So China is now paying us billions of dollars in tariffs.” He added later, “It will be a lot of money coming into the coffers of the United States of America.” The truth is more complicated.

Tariffs that are optimal in theory can be suboptimal in practice. Trading partners tend to retaliate. Plus, it’s tough to design a tariff whose costs are borne mostly or entirely by supplying nations. The early rounds of U.S. duties in the current conflict might have partially fit the bill because they were applied mainly to products for which the U.S. could play different supplying nations off against one another. But as the trade war expands, it’s covering more products with few sourcing options. For goods in which a single foreign country is the sole or dominant supplier, economists say, American customers will end up paying pretty much every penny of the duties. Says Pugel: “If U.S. buyers are desperate to get a Chinese product, the price in the U.S. is going to go up.”

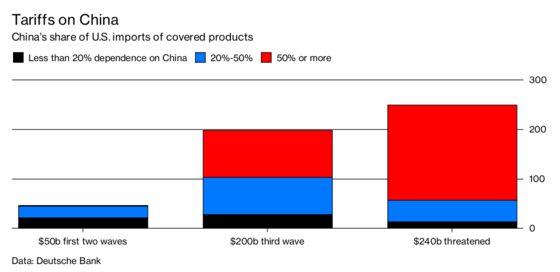

In the first two volleys of U.S. tariffs on China, which covered $50 billion worth of imports, only $1 billion were products where China had a dominant market position, according to a calculation by Deutsche Bank AG. In the latest round, which took effect on Sept. 24, American consumers are more vulnerable to price increases: Almost half of the $200 billion worth of products subject to the 10 percent duties come mainly from China. Things will get even worse for consumers if Trump makes good on his threat to place tariffs on the rest of Chinese imports, because for about 80 percent of the products, China is the majority supplier.

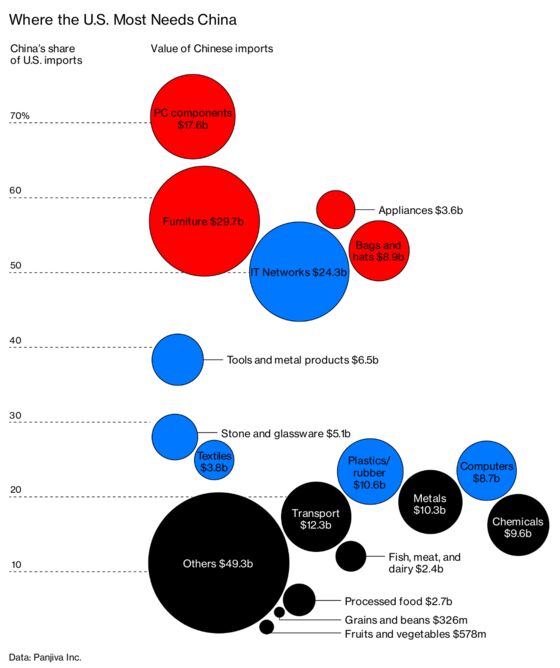

Electronic components, furniture, appliances, and networking gear are among the products under tariff for which the U.S. relies most heavily on China, according to Panjiva Inc., a unit of S&P Global Market Intelligence that specializes in supply chain data and analysis. For some specialty items such as frogs’ legs, boars’ bristles, eels, and tin and silver ores, 90 percent to 100 percent of U.S. imports come from China, data assembled by Panjiva show. At the urging of American companies, U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer spared from tariffs some products for which the U.S. is extremely dependent on China, including rare earth metals that are used in powerful magnets, smartwatches, Bluetooth devices, and bike helmets.

Who actually ends up footing the tab for the tariffs isn’t as obvious as it might appear at first glance. There’s no guarantee that the full levy will be passed along to the consumer via a higher price. The retailer, wholesaler, shipper, foreign manufacturer, and even the manufacturer’s suppliers may choose to, or be forced to, swallow some of the cost. The division depends on each player’s bargaining power, says Menzie Chinn, a University of Wisconsin at Madison economist. In the extreme case that the Chinese side absorbed the entire cost, it would be as if China paid the tariff. In reality, economists and company executives say, the U.S. side is mostly bearing the brunt.

In July, Coca-Cola Co. cited U.S. metals tariffs, which weren’t directed solely at China, as a justification for raising U.S. soda prices. Home Depot Inc. Chief Financial Officer Carol Tomé, in an August interview with Bloomberg News, said the retailer was allowing its suppliers to fully pass along their tariff-related cost increases. Whether Home Depot in turn passes them to its customers depends on the circumstances, she said. In the case of washing machines—which are subject to a 20 percent tariff regardless of where they’re from—“we pushed the cost increase to our consumers,” Tomé said.

One reason Americans often pay the lion’s share of a tariff is that foreign suppliers have nothing left to give. Their margins are already squeezed by hard-bargaining American retailers such as Walmart Inc. and Amazon.com Inc. Also, switching suppliers to avoid tariffs isn’t easy, says David French, chief lobbyist of the National Retail Federation Inc. China has a large, skilled workforce, reliable energy, and an excellent transportation network, he says; retailers “have looked elsewhere in the world, and there aren’t many” other sources immediately available.

It’s sometimes hard to pinpoint the impact of tariffs because other factors, such as consumer demand and raw materials costs, are also fluctuating. For example, critics of tariffs point to a surge in prices of large residential washers after the 20 percent duties were announced in January. The three-month average price through July was up 44 percent from the three months through April. But the average price was 22 percent lower than it was in the three months through December because of other market forces.

Metals markets are also hard to read. U.S. steel prices are up—as one might expect, given 25 percent tariffs. “It might not be that there is a shortage, but there’s concern and fear of a shortage,” says John Barton, a senior vice president at the transportation design firm HNTB Corp. On the other hand, U.S. aluminum prices are down despite 10 percent tariffs. An abundant worldwide supply of aluminum and fears of slowing economic growth have driven down the global benchmark price from its spring highs (even as Americans pay more than buyers in other countries because of the added levy). “It’s like the tide going out, lowering all boats,” says John Mothersole, an analyst for IHS Markit Ltd.

When the situation is reversed and other countries impose tariffs on the U.S. goods, American companies are often forced to make price concessions to maintain market share. Harley-Davidson Inc. said it would have to eat Europe’s new 25 percent tariff on motorcycles, amounting to about $2,200 per bike, to avoid losing customers. (To avoid the duties, it will produce motorcycles for the European market in Europe.) In July, Ford Motor Co. said that for now it wouldn’t raise prices on Fords and Lincolns shipped to China, choosing to absorb the hit from fresh Chinese tariffs. And American soybean farmers have had to cut prices to keep from losing sales in China. “By no means is the American soybean the only option the Chinese buyer has,” says Brennan Turner, chief executive officer of FarmLead Resources Ltd., a specialist in grain data.

Aside from taking money out of American consumers’ wallets, U.S. tariffs could inadvertently speed China’s push into advanced technologies. That’s because they apply to the full value of a product that comes from China even if Chinese workers did only the final assembly. The duties create an incentive for Chinese companies to shift low-margin assembly jobs to countries that aren’t subject to tariffs—freeing Chinese workers to do more valuable work. “You’re certainly going to see that kind of thing if this lasts for any length of time,” says Sherman Robinson, a nonresident senior fellow of the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington. In short, there may be an “optimal tariff,” but this doesn’t look like it. —With Matt Townsend and Joe Deaux

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Cristina Lindblad at mlindblad1@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.